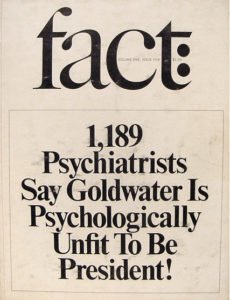

In 1964, Fact magazine published a survey of psychiatrists that claimed to show that Barry Goldwater was psychologically unfit to serve as president. The article set off a major controversy. Goldwater sued for libel and won. And the American Psychiatric Association (APA) adopted an new ethical principle that quickly became known as the Goldwater Rule: “it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion [on a candidate for public office] unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.”

In 1964, Fact magazine published a survey of psychiatrists that claimed to show that Barry Goldwater was psychologically unfit to serve as president. The article set off a major controversy. Goldwater sued for libel and won. And the American Psychiatric Association (APA) adopted an new ethical principle that quickly became known as the Goldwater Rule: “it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion [on a candidate for public office] unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.”

The Goldwater Rule is still among the APA’s ethical principles, but it only binds psychiatrists. This year, a number of psychologists have offered professional opinions on Donald Trump, whose candidacy and political personality have struck many observers as unusual. For example, in the June issue of The Atlantic Monthly, Dan P. McAdams, Chair of the Psychology Department at Northwestern University, published a long piece on “The Mind of Donald Trump.”[1] Such articles have in turn led to articles, such as this one from Tuesday’s New York Times, recalling the Goldwater Rule and musing on what limits psychologists and others with apparent professional expertise should place on diagnoses-from-afar of candidates.

The chief concern that led to the Goldwater Rule in 1964 was that psychiatrists should not claim to be able to diagnose people from afar. These days there is a further concern: that even if one could diagnose a candidate, the notion that a psychiatric disability ought to be seen as disqualifying one from office is the sort of ableist stigmatization of mental illness that we have worked hard to avoid in other areas of our culture. Medieval historian and disability rights journalist David Perry – who blogs at How Did We Get Into This Mess? – has been among the most prominent voices making this point, though as he points out, he is far from alone. Kim Sauder, who blogs at crippledscholar, has argued

:

People are using mental health speculation as a way to discredit Trump and make him appear incompetent. This is deeply stigmatizing to people with mental health diagnoses.

If the logic is that by framing Trump as having a mental illness makes him unfit for the presidency then the message is that mental illness is equated with incompetence and that is a dangerous thing to not only assert but to advocate which is exactly what anyone saying “Trump is [insert usually bigoted term for mental illness here] are doing.

Bigotry, Sauder argues, is not a mental illness and shouldn’t be confused with one.

If Goldwater is seen as the paradigmatic case of psychiatric diagnostic overreach in politics, Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton is the figure most often referred to by those concerned with the stigmatization of mental illness in our political life. Eagleton was McGovern’s initial running mate in 1972 until, shortly after the Democratic Convention, it was revealed that he suffered from depression and had undergone electroshock therapy. After days of public criticism and pressure on the campaign, Eagleton left the ticket only eighteen days after he was nominated.

Earlier this summer, a group of psychotherapists attempted to get around these objections by issuing a “public manifesto” entitled “Citizen Therapists Against Trumpism.” They were not, they insisted, trying to psychologize a person, but rather a movement. Although speaking as therapists, the authors of the manifesto were, in effect, writing about social psychology. The heyday of understanding politics through social psychology was the mid twentieth century. Before, during, and immediately after World War II, scholars like Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer and mental health professionals like Richard Brickner tried to explain fascism in social psychological terms. These theories were easily adapted to explain Communism. In The Vital Center, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., understood “Doughface progressives” – his term for fellow travelers – as driven principally by psychological weakness:

[T]he Doughface really does not want power or responsibility. For him the more subtle sensations of the perfect syllogism, the lost cause, the permanent minority, where lie can be safe from the exacting job of trying to work out wise policies in an imperfect world. Politics becomes, not a means of getting things done, but an outlet for private grievances and frustrations. The progressive once disciplined by the responsibilities of power is often the most useful of all public servants; but he, alas, ceases to be a progressive and is regarded by all true Doughfaces as a cynical New Dealer or a tired Social Democrat.

Having renounced power, the Doughface seeks compensation in emotion.

These social psychological understandings of politics never entirely went away. Indeed, one mid-20th-century social psychological concept — the “authoritarian personality” – has enjoyed a tremendous revival in the last decade or so. John Dean’s critique of the George W. Bush administration Conservatives Without Conscious (2006) drew extensively on the work of Bob Altemeyer, a University of Manitoba political scientist who had been working on right-wing authoritarianism since the 1980s. Since the middle of the last decade, the idea that authoritarianism as a social type explains the recent history of the American right has had a strong presence in popular political discourse. A Politico Magazine piece from January of this year, for example, argued that authoritarianism was “The One Weird Trait That Predicts Whether You’re A Trump Supporter.”

On a more mundane level, Americans often turn to psychological explanations for voting behavior, though usually of those with whom we disagree. Clinton supporters in the primaries frequently accused Sanders supporters of being motivated by misogyny. Now many accuse those thinking of voting for third party candidates of immaturity or narcissism.

And while psychologically diagnosing political candidates from afar remains controversial and distasteful to many, discussions about candidates’ “temperament,” a term used to describe someone’s mental and emotional make-up, are nearly universally seen as fair game.

The widespread use of psychological concepts in our political talk points to a deeper fact: psychology and politics are deeply bound up with each other in our culture in ways that go far beyond what psychiatrists and psychologists might have to say about candidates or voters. Notions of psychological normality are intertwined with ideas of individualism. Happiness is both a core goal of psychological practice and an important touchstone in our nation’s founding document. There is much to be gained by understanding the deeper links between political and psychological ideas in America, both today and in the past.

_____________________________

[1] This week the Trump campaign got into the act, repeating long-standing conspiracy theories about physical and mental conditions that Hillary Clinton supposedly suffers from.

13 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Just an addendum to Ben Alpers’ timely posting. Older readers of the blog may remember the controversy over the publication of Robert Bullitt’s and Sigmund Freud’s (in)famous psychoanalysis of Woodrow Wilson published in 1966 and reviewed in quite negative terms by both Richard Hofstadter and Erik H. Erikson in “The New York Review of Books” (February 9, 1967). The Bullitt-Freud book was clearly an early violation of what has become known, as Ben notes, “the Goldwater rule.” Whatever else was true of their analysis of Wilson, it did neither Bullitt’s nor Freud’s reputations any good.

Two other things strike me about this case. First, shorn of the psychological/-analytical jargon, the Bullitt-Freud analysis is pretty close to other conclusions, e.g. the Georges, about Wilson’s psychological profile. Thus, it wasn’t so much that Freud and Bullitt were wrong but that their analysis was too crude and mechanical. Second, as Ben also notes, most of us historians and journalists have no problem generalizing about artists, leaders, and politicians at the drop of a hat and with the minimum amount of psychological training and insight. This might be called the Theodore H “Teddy” White syndrome. Two examples.One positive diagnosis that turns up with tiresome regularity is that “X is a man/woman comfortable in his/her own skin.” This insight(sic) is followed closely by idea that the desire to conciliate others on the part of a leader is linked with having grown up in a broken home where the leader-to-be had to mediate desperately between parents. I’m sure there are other such bromides and boilerplate judgements.

Thanks for this post, Ben. There is so much here. I had missed, for instance, that McAdams piece from June. I’m reading it now. And thanks to Richard King for making me aware of the Bullit/Freud analysis of Wilson. (Aside: When was that published? During Wilson’s life, or after?)

A speculation: I think that psychological/psychiatric analyses are proxies when we don’t have a strong sense of a candidate’s guiding philosophies or ideologies. People want to know what drives other people to seek power. When they don’t express their deepest motivations, or appear inconsistent, people resort to psychology.

PS: Two mentions of Thomas Eagleton in one week at the blog! I don’t know what this means, but I just wanted to note the randomness of it.

I’m curious whether there is, or should be, a Goldwater Rule for historians. I’m currently researching a historical figure whose mother clearly had a mental illness (and was diagnosed as such at the time). However, I believe the original diagnosis was incorrect, and that her condition was actually a more recently-discovered one for which a diagnosis was not available at the time. I don’t know what to do with this, as a scholar, because I don’t feel qualified to diagnose her, but at the same time I don’t want to let a faulty diagnosis stand simply because it was the best available at the time. And this question seems to matter to the story I’m telling, as it paints the mother’s behavior in a very different light depending on which diagnosis is the correct one.

I suppose you could consult w a medical person about the evidence and pass the responsibility for diagnosis, so to speak, on to the consulting expert (Goldwater Rule presumably wouldn’t apply to that person in his/her prof capacity b/c it’s not a candidate but a historical figure that’s in question; plus as the OP says, the Goldwater Rule applies to psychiatrists but there is no comparable rule apparently for psychologists). You probably can’t avoid doing something like this if the issue matters, as you say it does.

Since there was a whole mini-genre of psychohistory in recent decades, I suspect that, precisely because historians are not psychologists or psychiatrists, there is perhaps more tolerance for their engaging in diagnosis, retrospective or otherwise. (And sometimes it’s probably almost unavoidable.)

p.s. I meant, of course, ‘armchair diagnosis’ or diagnosis in the absence of personal contact with the subject.

Surely I can’t be the only person here who had to read “psycho-history” in graduate school? Several of my advisors attempted psychologized biographies of figures in their field, and the results were kind of embarassing. Freudian analysis of 19th century Japanese family systems…

On the original topic, there’s a huge gray area between psychiatric diagnosis and “questions of character” that seem to be legitimate elements of an election debate…

Thanks for this Ben, you are absolutely right this is a deep (but productive!) rabbit hole.

Argumentatively, I’ve always found the attempt to discredit through psychology to be highly problematic, akin to trying to discredit someone through accusations of stupidity. As you point out, its ultimately linked to individualism, where the policies a person promotes or attacks is somehow only as or even less important than their personal “qualities.” One of many unfortunate consequences to a clear understanding of politics that individualism introduces.

But that soap box aside, psycho-history often reveals as much about the historians as their subjects. I’m aware that there was once quite a literature, for example, in exploring whether John Brown was insane. It is interesting to me, however, that it seems like an obvious possibility that someone willing to dedicate their life (and sacrifice it, in the end) to attack and end slavery would probably be insane. I mean, the particulars of his plan being a good one or not aside, it is not at all clear to me that the extraordinariness of such a person is obviously resolved by considering him crazy.

Anyway, as I said, lots of stuff to chew on here.

I’m not sure *exactly* what Ben meant in the OP when he wrote that “notions of psychological normality are intertwined with individualism,” but putting that aside, I don’t think I agree with you on the question of a candidate’s personal qualities. These can be very important in some cases, perhaps even of an importance rivaling policy proposals. If Nixon had been president during the Cuban missile crisis rather than Kennedy, would the outcome have been the same? Not sure, but I’m glad he wasn’t. Similar questions arise in connection with how Trump might behave, for example, during a crisis. Seems to me the question of character and ‘temperament’ is relevant here, even if the prospect, say, of global nuclear war today does not loom anywhere near as large as it did, or in the way it did, in 1962. There are crises short of that which could still produce very bad results on a very large scale if mishandled. And as J. Dresner suggested, there’s a difference between questions of character and psychological/psychiatric diagnosis, or at least a large vague area in between.

Re Nixon and Cuban Missile Crisis… I would argue, and not alone, that Khrushchev attempted his missile gambit in Cuba after sizing up Kennedy as a very weak man at their Vienna Summit in 1961. So if we are to indulge counterfactuals, I argue that there would probably not have been such a crisis at all had Nixon been President.

And as for counterfuturals (great neologism), We saw how Hillary Clinton acted under pressure when the US compound in Benghazi was attacked. Certainly fair to wonder about Trump in a crisis, but we already know the Clinton failed to act to save her people, and then lied and continued lying for years afterward, for political expediency (NOT national raison d’etat).

So maybe best to just leave aside all that speculation that says more about you than it says about your subjects?

Re Tim Lacy’s question: the manuscript of “Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study,” along with a Foreword by Bullitt and an Introduction by Freud was first published in 1966. I have the Avon Discus paperback, first published in 1968. Both Erikson and Hofstadter make valiant, sometimes convincing, efforts to distance Freud from what they consider an embarrassing document. At least Freud admitted quite openly that he didn’t like Wilson. But I don’t think psycho-history was just reductionist, long-distant character assassination. Erikson’s works on Luther and Gandhi, for example, are often compelling and insightful. My own sense is that psycho-analytic theory is most productive when used to identify broad patterns of concerns and motifs over time within a society as they are expressed in a subject’s life and actions. But just like no good analyst jumps right in with a diagnosis of his/her patient after a few sessions, no decent psycho-historian shoots from the hip when offering an analysis of an historical actor. In both cases much evidence and experience, combined sensitively with theory, need to be brought to bear. Thus, I would be suspicious of analytic judgements on Trump, for example, as highly suspect, even when they seem to be “right.” The insights haven’t been “earned,” as it were. More often, they are of the nature of frontier justice: “yeh, we’ll give you a fair trial. And then we’ll hang you.”

Thanks, Ben, for a rich discussion that raises many knotty issues in psychology, politics and history.

Just to follow up Richard King’s point about psychohistory — it was always about much more than biography, reductionist or otherwise. And of course the yet unwritten history of intersections of psychoanalysis and history is but one part of the topic of psychology and history … not to mention of politics, and political history.

A good place to start is Joan Scott’s “The Incommensurability of Psychoanalysis and History,” History and Theory, Feb 2012, in part because she argues that earlier psychohistory of Erik Erikson and the rest mainly appropriated or imported psychoanalytic terms and concepts as tools for doing history in conventional ways, instead of putting the two fields into troubling confrontation, especially around how it challenges historians’ understandings of time. Cristian Tileaga and Jovan Byford, eds, Psychology and History. Interdisciplinary Explorations, 2014, is one of several recent works that explore this particular aspect of the widespread current interest in interdisciplinarity.

Also, while as Ben said, the seeming inescapability of psychological terms is most directly understandable as a feature of dominant individualism [the language of the self, coming of “psychological man,” etc.] there are equally important psychologies of the social, concerned with the typical or modal individuals of culture and personality, mass psychology; the nominalism of the social as aggregated psychologies; and analogies treating groups as individuals writ large, as in the legal personality of corporations and nation-states.

Replying to MJH’s comment upthread:

(1) You may well be right that the missile crisis would not have occurred if Nixon had been elected in ’60 since Khrushchev would not have been tempted to test him in the same way.

(2) Not going to get into Benghazi.

(3) I’m not inclined to retract the basic point that character/temperament (or substitute whatever term you want) has some relevance.

(4) You say that my speculation says more about me than it does about my “subjects.” What does it say about me? Why not be explicit in your criticism or insults? If I couldn’t take harsh or pointed criticism, I wouldn’t be commenting on a blog in the first place.

correction: sorry, that should be MHJ (I reversed one of the initials).