The Fourth of July is, by happy circumstance, generally a good day for historical editors

. Over barbecues and across beaches, from sea to shining sea, folks seem glad to talk about founding-era documents and—critically—the many drafts that manuscripts arise from. Huzzah for the archivists who salvaged the Declaration for its trip down the Delaware, we say, and for the librarians who align digital worlds to parse the Magna Carta next to the Bill of Rights. Setting the revolutionary drafts in global context is one route to the past. Another way to think about the Declaration is to focus on its local legacies, to continue my experiment in producing “small-batch” intellectual history.

For, months before that “memorable Epocha” of 2 4 July 1776, as Pauline Maier showed in American Scripture and in its appendix, many declarations of independence rippled through the colonies. To townspeople, the language of revolution must have seemed both old (English liberties to uphold) and new (popular sovereignty replacing monarchical rule). When they first spoke of an American revolution in print—before Thomas Jefferson and his colleagues drafted a document intended to serve as a “plain” and “common sense” argument that reflected an “expression of the American mind”—what did “we the people” declare? To the drafts!

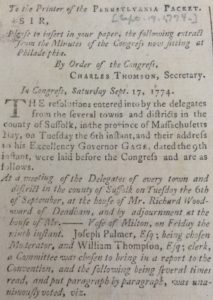

If I had to choose, the language of the Suffolk Resolves (adopted by Congress on 17 September 1774, thanks to one of Paul Revere’s less-famous rides) might be my favorite. Officially, the Massachusetts Government Act hindered town meetings, and so by the fall of 1774 New Englanders had embraced another path: county conventions. The first draft of the Suffolk Resolves came via the Adamses’ family doctor, Joseph Warren. Three hard days of editing, while townsmen toggled between Dedham and Milton, yielded a final document that won the support of Congress and even cheered up one prickly delegate. “This was one of the happiest Days of my Life,” John Adams wrote in his diary of the Resolves. “In Congress We had generous, noble Sentiments, and manly Eloquence. This Day convinced me that America will support the Massachusetts or perish with her.”

They did not hold back. Take the opener, and between the pop-fizz-clink of fireworks and (safe) fun, try it aloud: “Whereas the power but not the justice, the vengeance but not the wisdom of Great-Britain, which of old persecuted, scourged, and exiled our fugitive parents from their native shores, now pursues us, their guiltless children, with unrelenting severity: And whereas, this, then savage and uncultivated desart, was purchased by the toil and treasure, or acquired by the blood and valor of those our venerable progenitors; to us they bequeathed the dearbought inheritance, to our care and protection they consigned it, and the most sacred obligations are upon us to transmit the glorious purchase, unfettered by power, unclogged with shackles, to our innocent and beloved offspring. On the fortitude, on the wisdom and on the exertions of this important day, is suspended the fate of this new world, and of unborn millions.”

They did not hold back. Take the opener, and between the pop-fizz-clink of fireworks and (safe) fun, try it aloud: “Whereas the power but not the justice, the vengeance but not the wisdom of Great-Britain, which of old persecuted, scourged, and exiled our fugitive parents from their native shores, now pursues us, their guiltless children, with unrelenting severity: And whereas, this, then savage and uncultivated desart, was purchased by the toil and treasure, or acquired by the blood and valor of those our venerable progenitors; to us they bequeathed the dearbought inheritance, to our care and protection they consigned it, and the most sacred obligations are upon us to transmit the glorious purchase, unfettered by power, unclogged with shackles, to our innocent and beloved offspring. On the fortitude, on the wisdom and on the exertions of this important day, is suspended the fate of this new world, and of unborn millions.”

The Suffolk Resolves, laden with grievances against British rule and invested in popular sovereignty, were one of many preambles that the Declaration of Independence enjoyed. (Resource tip: Check out Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Series 4, 5, 6 for more). As a text, the Suffolk Resolves may lack Jefferson’s poise and Benjamin Franklin’s charm, but the lines reflect Adams’s fire. The document stands as an intellectual artifact of the New England town spirit in transition, too, a rural tide moving from angry colonists to organized citizenry. It is a wholly new body politic, forming and arguing and declaring all at once.

Rereading their words, I thought of an excellent panel on town recordkeeping I heard at the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture conference in June. The town clerks authored the local identity, as the panelists explained, by choosing what to set down as history and what to skip in telling the “official” story. Today, we might call that colonial data curation. Declaration-drafting mattered a great deal, then, since it gave people time and space to practice the new language of revolution within a familiar community. Getting into the cultural habit of declaring independence, as similar events in Tryon, N.C. and Mecklenburg, N.C., show, is something that Americans have worked at for a long time. Unscripted town meetings, like the gatherings that led to the Suffolk Resolves, radically reshaped the intellectual ecosystem at a neighborhood level. Local declaration signers are likely those we do not know well (yet), and town histories can fade. Their ideas hover here, loose, in the declarations before the Declaration, at the moment when the local became epic.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Sara: Love this. I really liked this line, near the end: “Getting into the cultural habit of declaring independence…” I don’t think it’s a habit Americans have lost, for better or for worse. – TL