Guest Post by Ryan Donovan Purcell, Assistant Book Review Editor

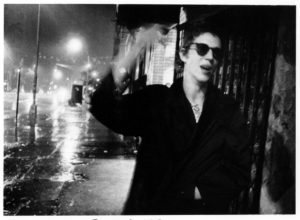

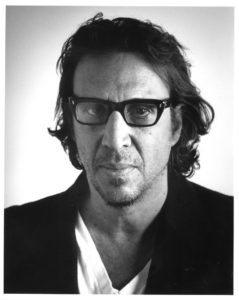

I had no expectations when I visited Fales Library at New York University to look at Richard Hell’s papers. The punk rock pioneer deposited his materials there in 2004, and I had since been curious to explore their contents. His journals and notebooks were among the most intruding items listed in the online guide. I suspected they would contain reflections of New York City during the early 1970s, and how urban decay might have influenced his art. That was my hope, not expectation.

I found instead (among other things) a deep repository of ideas. More than lyrics and love notes, I found metaphysical meditations, raw explorations of the roles of sex and drugs in  spiritual life, and musings on the artistic process. Most shocking was the precocity of his early journals, 1969-70. They show Hell, no more than twenty-one years old, vigorously questioning his role in a world of profound ideas. He sketched an intricate cosmogony of bodily experience, which seems to have fueled his artistic production. And the journals show the evolution of his ideas over time, from angst-filled youthful tears to sophisticated dissections of his artistic practice. “I want to write with the absoluteness of a dead man,” thought a twenty-year-old Hell in 1969. “What is is: they can have perfect secrets while naturally maintaining their intimacy with the universe.” These early journals, moreover, might reflect the near mystic nihilism Hell later infused into what came to be known as a punk aesthetic. “I want to be dead… What I love is the freedom of death (attainable while still breathing).”

spiritual life, and musings on the artistic process. Most shocking was the precocity of his early journals, 1969-70. They show Hell, no more than twenty-one years old, vigorously questioning his role in a world of profound ideas. He sketched an intricate cosmogony of bodily experience, which seems to have fueled his artistic production. And the journals show the evolution of his ideas over time, from angst-filled youthful tears to sophisticated dissections of his artistic practice. “I want to write with the absoluteness of a dead man,” thought a twenty-year-old Hell in 1969. “What is is: they can have perfect secrets while naturally maintaining their intimacy with the universe.” These early journals, moreover, might reflect the near mystic nihilism Hell later infused into what came to be known as a punk aesthetic. “I want to be dead… What I love is the freedom of death (attainable while still breathing).”

July 1969

What does it mean to create? What is the role of an artist in society? We see Hell, in these early journals, grasping for meaning in everyday life, yet with a remarkable acuity, prescient of his later role in helping to fashion an aesthetic movement. “There is no such thing as decadent art. It’s a contradiction in terms,” Hell wrote in the spring of 1970, only twenty-one years old. Artists, young Hell reflected, are “explorers of the frontiers of perception and sense—consciousness.” They are society’s “bullshit detectors,” he wrote, imbued with the moral responsibility of nudging society in the right direction; yet, they are conscious of the “fatal results of taking a side to the extent that they are bounded by its dogma.” It is inquiry and self-analysis like this, which pervade his early journals, and at such a young age, that forged the intellectual currents, the ethics and aesthetics that can be traced throughout Hell’s oeuvre.

An arch of self-examination runs throughout Hell’s journals, naturally. Yet what stand out are his Hemingway-esque writing prescriptions and experimentations with procedure. “I more or less write in the same way that I eat,” Hell wrote in 1971, “—ignoring the need until it becomes overwhelming, when I gorge myself—with snacks in-between.” Other explanations of his process, like one written in September, 1974, are more formulaic, but still illuminating: “My best procedure—to know I’m writing— is to think of my heroes—spread around me good books and pictures. It’s like squeezing a lemon. Have a bottle of wine.” Writing, for this forerunner of punk rock, was a matter of developing attitude. Such an attitude, however it is manifested, is a “result of perceiving a void,” intellectual or otherwise, in which the artist might shape new ideas.

We see Hell playing with free-association, ostensibly influenced by William Burroughs’s cut-up poetry: “Write one good, interesting line,” Hell jotted in 1969, “then title it with a line of equal length that seems as far from the word titles as possible. Experiment in this line.” His handwriting is messy, at times barely legible. He preferred to print on typewriter, a mode he thought contributed to the development of his style. “Must always remember to let no conventions interfere with the writing,” he wrote again in 1969, “as the typewriter reminds—remember again to believe yourself—remember that the reverse of everything I say is true.” Such Borgesian absurdity and contrariness is later evident in songs like “Blank Generation,” “That’s All I know (Right Now),” “Kid with the Replicable Head,” and which moreover illustrates the irony of punk logic. “The art of plagiarism,” Hell wrote in the winter of 1974, “Simpering wimps alone use quotation marks.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TP3x-VdOb44

Much of Richard Hell’s thought and art were derived from bodily experience. His writings exhibit an interest in the corporeal beauty of everyday life, however decadent or flowery. Direct experience, for Hell, was a yardstick of artistic integrity. The difference between mere “literature” and art, accordingly, is a matter of phenomenology. Where the former might portray a specific reaction to an experience, like a “description of a fight that gives the reader the sense of being punched in the jaw,” art is the experience; “the reader is punched in the jaw and feels his own

spontaneous reaction to being hit.” From  passages like these I began to understand the literary nature of Hell’s punk performances. His songs were not merely songs, but means of probing and articulating the human experience.

passages like these I began to understand the literary nature of Hell’s punk performances. His songs were not merely songs, but means of probing and articulating the human experience.

“I am sick of thought,” Hell wrote in the winter of 1976. “I want something palpable and beautiful. But nothing a human can do is palpable. The history of art is men consoling themselves in the face of this fact. What remains are drugs and sex.” Bodies, for Hell, are conduits to the spiritual. Sex, he wrote in 1979, “is just the name for all the ways it’s possible for a human to transcend himself by unhesitatingly devoting his being to another human.” In this way, one’s self (the qualities of a human that distinguishes ‘one’ from ‘another’) becomes an amalgamation of “whatever number of bodies and souls” at the moment of “absolute surrender to the other.” Sex (and drugs), for Hell, seems almost synonymous with art and love; all are means of realizing ‘God’ (“By God I mean the sum of existence that includes human consciousness”). Love, after all, Hell wrote in 1974, is “really eternal when you’re full of heroin.” Ideas like these place Hell firmly in a romantic intellectual tradition ranging from William Burroughs to Arthur Rimbaud, and the Marquis de Sade.

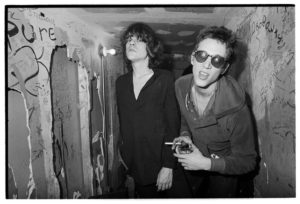

Richard Hell’s journals surpassed my expectations. Honestly I didn’t know what to expect. What I discovered was a cache of ideas, and a chronology of Hell’s intellectual development. These journals reframe the popular image of the gritty New York punk scene of the early 1970s, which some might consider anti-intellectual. Rather, these journals  show us a new depth of intellectual innovation during that time. Early punk rockers were young musicians, but also philosophers, and writers, artists in every sense, attempting to make sense of their world, during a time of tremendous political, economic, and social transformation. In Richard Hell’s journals I found a raging current of thought, about which very little has been written. I found out how much I didn’t know about Richard Hell and the so-called “Blank Generation.” It is evermore clear, however, that historians of the 1970s certainly have their work cutout for them.

show us a new depth of intellectual innovation during that time. Early punk rockers were young musicians, but also philosophers, and writers, artists in every sense, attempting to make sense of their world, during a time of tremendous political, economic, and social transformation. In Richard Hell’s journals I found a raging current of thought, about which very little has been written. I found out how much I didn’t know about Richard Hell and the so-called “Blank Generation.” It is evermore clear, however, that historians of the 1970s certainly have their work cutout for them.

http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/fales/hell/

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Richard was born in October (in 1949), so he is actually one year younger in every instance that you cite his age; i.e., when you call him twenty, he was actually nineteen.

Artists as “bullshit detectors.” I love that, because so many people like to think of artists as the unproductive members of society. – TL

Ryan, I really loved this post. I was especially intrigued by your effort to regard Hell’s thoughts about the body as a form of intellectual work. My own research at the moment is investigating a similar conjunction — attitudes about the body and democracy in Whitman and the American pragmatists — so I’m very curious to learn more about how you frame these issues conceptually as a form of intellectual history. I have found the philosopher Richard Shusterman’s concept of “somaesthetics” to be helpful in thinking about the relation of the body to philosophical discourse — you might check him out. While this post is mostly biographical, I can imagine how it could fit into a kind of intellectual history of 1970s NYC that would include Patti Smith and other “poets” in the downtown scene, at St. Marks and elsewhere, and treated as intellectuals of sorts. For some reason we seem to resist including musicians in our intellectual histories, perhaps because music is so rarely reducible to words. I’d be curious to see how you would compare Hell’s journals and letters to his publicized lyrics and place these materials in the context of other artists of his time and place. Hopefully some of these issues will be broached at this year’s conference!