As with any era of intellectual history, the post-civil rights period (or whatever future historians will call this era) requires significant scrutiny of its works of art, literature, and general culture. Several novels have been released in the last year that offer great detail of the black experience across the African Diaspora. Covering genres as vast as literary fiction, science fiction, and alternate history, these novels will no doubt be studied by intellectual and cultural historians for what they say about what it means to be black in the early 21st century.

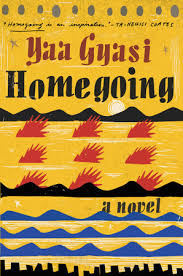

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi has already captured the interest of many critics. The novel focuses on two families descended from West African tribes—one ultimately enslaved and sent to North America, the other experiencing the history of West Africa and the long period of interaction between Africans and Europeans in that part of Africa. Homegoing

is an ambitious novel about some of the myriad threads that make up the  African Diaspora. Gyasi’s own history, in some ways, matches what happens to the characters in the book: she was born in Ghana, but lived in Alabama from the age of nine. The novel has already received praise for its writing, scope, and historical depth. Furthermore, I believe the novel—like Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah—shows the unique cultural and social relationships between African Americans and West African immigrants to the United States.

African Diaspora. Gyasi’s own history, in some ways, matches what happens to the characters in the book: she was born in Ghana, but lived in Alabama from the age of nine. The novel has already received praise for its writing, scope, and historical depth. Furthermore, I believe the novel—like Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah—shows the unique cultural and social relationships between African Americans and West African immigrants to the United States.

Where Homegoing is an epic of dizzying historical scope, Blackass offers a biting social commentary on life in modern Nigeria. A. Igoni Barrett’s story features a Nigerian man waking up one day to find himself with (mostly) white skin.[1] Viewing the problems of race and ethnicity in modern Nigeria, Barrett’s novel will certainly be worth reading. All comparisons to Kafka aside, Blackass is also a wonderful reminder of just how much wonderful literature is produced on the African continent year to year.

Another intriguing work is Underground Airlines by Ben Winters. Taking place in an alternate timeline where the American Civil War was avoided and several states still have slavery, Underground Airlines has earned critical acclaim for a story that, despite the changed timeline, seems far too eerily similar to the real world. Alternate history stories can often play with images and tropes we know from real life—Confederate States of America is a great example, and the first season of The Man in the High Castle also provided some chilling moments of what life could have been like in an Axis-dominated America—and it appears Underground Airlines is no different. It is worth noting that the novel’s debut generated some controversy, as an interview with Winters pointed out his own trepidation about writing the story considering his identity as a white man. In an age of Underground, a reboot of Roots, and this fall’s release of The Birth of a Nation, Underground Airlines speaks to a continued interest in the era of slavery in American history—albeit, in this case, as a modern and fictional presence.

Finally, the growth of “Afrofuturism” will bear some study by future intellectual and cultural historians. Books such as Ytasha Womack’s Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture give background to this subgenre of speculative fiction. As a storytelling device, Afrofuturism imagines a future (or sometimes a past or even a present) centered around a black experience enhanced by science fiction or the fantastic. To make a long story short, the idea of Afrofuturism has links with African American cultural and intellectual history, going back well over a century. Martin Delany’s Blake, or the Huts of America (1859) is an intellectual grandfather of the genre, imagining a successful slave revolt in the American South. W.E.B. DuBois’ “The Comet” (1920) imagines a world where the last two humans left alive are a black man and a white woman. And of course we have more recent iterations of this genre—Brother From Another Planet (1984), the short story- turned HBO short film “The Space Traders” written by Critical Race theorist Derrick Bell, and now Ta-Nehisi Coates’ run on Black Panther. His run has expanded to include a new series by Marvel Comics written by Roxane Gay. Speculative fiction has always been a place to imagine different futures–not to mention different pasts as well–so it is not surprising that writers of color are toying with the field even more re-think the place of African Americans in American society.

turned HBO short film “The Space Traders” written by Critical Race theorist Derrick Bell, and now Ta-Nehisi Coates’ run on Black Panther. His run has expanded to include a new series by Marvel Comics written by Roxane Gay. Speculative fiction has always been a place to imagine different futures–not to mention different pasts as well–so it is not surprising that writers of color are toying with the field even more re-think the place of African Americans in American society.

Fiction has a great deal to offer to intellectual historians. I’ve only noted a few examples here and stuck mostly to print media. It is an exciting time to consider the many ways writers are using novels, short stories, and comic books to re-imagine the black experience.

[1][1] The title of the novel, of course, gives some indication of why I say he is mostly white.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Yaa’s book has meaning for us and sorrow. I am glad I read it before the reviews.

There is plenty of material for historians to delve into discuss and compare to sixties and earlier writings

But for a non historian, curious, this book stands alone for us all to learn how we are now and then all complicit

It really does stand apart–it’s definitely an ambitious work, something of an “epic” in terms of African and African American history as fodder for literature.