[Editor’s Note: Full Stop recently celebrated the centennial of Albert Murray. The following guest post from Michael Schapira, who is an Interviews editor at Full Stop and teaches Philosophy at Hofstra University, introduces and links Full Stop’s commemoration for readers of our blog — Ben Alpers]

Centennials are convenient occasions to revisit, or in the case of Albert Murray, expose to a broad readership the prodigious career of an important figure in 20th century intellectual life. Murray would have turned 100 on May 12 (he passed away in 2013) and his birthday was commemorated with profiles in The New Yorker, The Nation, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. To those like me, familiar with the name but less familiar with the full body of work (extending beyond criticism and fiction to include his role in founding Jazz at Lincoln Center) these profiles are certainly helpful, but this week at Full Stop we thought we’d cut Murray a wider berth.

Centennials are convenient occasions to revisit, or in the case of Albert Murray, expose to a broad readership the prodigious career of an important figure in 20th century intellectual life. Murray would have turned 100 on May 12 (he passed away in 2013) and his birthday was commemorated with profiles in The New Yorker, The Nation, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. To those like me, familiar with the name but less familiar with the full body of work (extending beyond criticism and fiction to include his role in founding Jazz at Lincoln Center) these profiles are certainly helpful, but this week at Full Stop we thought we’d cut Murray a wider berth.

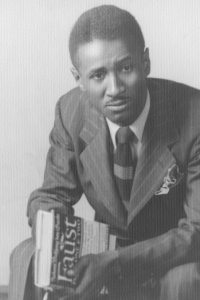

Murray, raised on the outskirts of Mobile, Alabama, is perhaps best known as a figure in Harlem’s post-war world of letters, where he lived from 1962 until the end of his life. Yet our commemoration of Murray begins in Morocco, where Murray was stationed from 1955-58 as an Air Force captain. He was invited by the U.S. Information Service to give talks on jazz in 1956 and 1958, with the goal of improving relations between the U.S. military and local intellectuals. Murray gave several presentations, in French, at the U.S. embassy in Rabat, the Maison d’Amérique in Casablanca, and elsewhere. Notices for these talks were printed in French and Arabic, and drew considerable local enthusiasm. The lecture published here, translated from the original French by Lauren Walsh, is one of Murray’s early, extended statements on Jazz, Blues, and black forms of cultural expression.

Thanks to his association with Jazz at Lincoln Center Murray is perhaps best known for his criticism and appreciation of this musical form (the first thing V.S. Naipal noticed up entering Murray’s home were “the worn sleeves [of Murray’s Jazz collection of jazz records) standing upright, filling many shelves.”). In 1994 Murray sat down with Wynton Marsalis to engage in an interesting, if not slightly polemical interview about blues and the more general question of artistic form, a topic of great aesthetic debate at that moment. As with the Morocco lecture, this interview is an excerpt from Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues, published this past May from University of Minnesota Press.

The editor of this collection, Paul Devlin, provides the most comprehensive assessment of Murray’s legacy (including some very contemporary thoughts on how Murray’s centennial was publicly marked in May by The New Yorker and others). In a three part interview with Andrew Mitchell Davenport Devlin charts Murray’s course on the intellectual and artistic current of 20th century American life, both locally and Harlem and more globally. Devlin has also included an interview he did with Murray himself in 2006 in preparation for what would eventually become Rifftide, a complicated history of jazz luminary Papa Jo Jones “as told by Albert Murray” and edited by Devlin.

Our commemoration concluded with an essay by the St. Lucia based Matthew St. Ville Hunte about Albert Murray and the Americas. Hunte argues that Murray belongs in the constellation that includes Eduard Glissant, Rene Menil, Antonio Benítez-Rojo, Alejo Carpentier, Llyod Best, and even C.L.R. James.

Our commemoration marks a midway point between Murray’s actual centennial and his ascension to one of the highest ranks of official recognition, the October publication of his collected essays by the Library of America (edited by Paul Devlin and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.).

We (the collective we of Full Stop editors who put this week together) would be very curious to hear where Murray stands in relation to the interests of USIH readers and contributors.

0