By Mira Siegelberg

This is the latest in our Roundtable series on Arendt and America. Here’s the introduction, Part One, and Part Two.

http://www.princeton.edu/sf/current-fellows/mira-siegelberg/

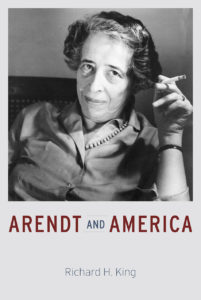

Richard King describes his masterful new book Arendt and America as an attempt to remedy the “lack of understanding of the impact of Arendt’s thought on American thought and culture and of the impact of the New World on her thought.” This is ultimately a too-modest assessment of the ambitions of the work since King’s unstated theme is historical judgment itself. Over the course of the study King demonstrates how comprehending Arendt’s efforts to think in time provides a critical perspective on Arendt’s thought at the same that it illuminates the broader relationship between historical interpretation and moral evaluation.

Arendt and America lucidly surveys Arendt’s encounters with American thinkers and political debates beginning with her discussion of political guilt and responsibility in 1945, through her public engagement with questions about the status of the American republic at the time of her death in 1975, before turning to the controversies surrounding Arendt’s legacy that continue to animate intellectual debate in the United States. Arendt famously eschewed the idea that one could establish a philosophical perspective on politics from outside the arena of collective political life. King’s reconstruction of her intellectual involvements during her years in the United States details how exactly she brought together interpretations of the political issues of her time with a more enduring set of theoretical and historical concerns. Though she has often been classed as an émigré intellectual, part of the mass migration of European intellectuals who sought refuge in the United States but brought their philosophical inheritance with them into exile, others have concluded that her mature theory was indelibly marked by an “American” mentalité. For the political theorist Judith Shklar, Arendt’s commitment to the United States may have at times excessively informed her thought. Shklar wrote that On Revolution, Arendt’s study of the shining moment of American foundation, “shows a patriotism that was not merely a refugee’s gratitude. To complain of unceasing declension is the deepest impulse of American patriotism, and Miss Arendt evidently shares it.” [i]

In Arendt and America, King provides a more measured portrait, detailing how Arendt sought to embed herself within the political culture and history of her adopted country, though there was much she failed to grasp. In a late essay from 1971 on “Thinking and Moral Considerations,” Arendt, who became preoccupied with the theme of judgment in  her last years, wrote that in moments of crisis the capacity to think and to judge particulars became the most significant political capacity. In this spirit, King is concerned with the sources of Arendt’s analysis and judgments and how her judgments evolved over time. King’s evaluation of Arendt derives, therefore, not from an analysis of the limits of her thought in philosophical terms but rather from the limits of her confrontation with political events and with history— with her judgment of the particular. It is the great triumph of the work that he proves that she can be evaluated on this terrain. King shows why historicizing Arendt’s particular approach to politics—and studying her efforts to think in time and in particular intellectual and political settings—allows a fuller appreciation of her intellectual legacy.

her last years, wrote that in moments of crisis the capacity to think and to judge particulars became the most significant political capacity. In this spirit, King is concerned with the sources of Arendt’s analysis and judgments and how her judgments evolved over time. King’s evaluation of Arendt derives, therefore, not from an analysis of the limits of her thought in philosophical terms but rather from the limits of her confrontation with political events and with history— with her judgment of the particular. It is the great triumph of the work that he proves that she can be evaluated on this terrain. King shows why historicizing Arendt’s particular approach to politics—and studying her efforts to think in time and in particular intellectual and political settings—allows a fuller appreciation of her intellectual legacy.

The work is poised between an appreciation of Arendt’s power as a historical thinker and a critical assessment of her blind spots when it came to comprehending the past and present of the United States. In an earlier edited volume, Hannah Arendt and the Uses of History, King considered Arendt’s critical legacy for historical interpretation, particularly one of the central insights of The Origins of Totalitarianism: that mass violence in Europe’s twentieth century could only be understood in relation to the history of western imperialism and race-thinking. In his current book, King seems particularly taken with the tension between the resources he finds in her thought for understanding American history and the evident limits of her understanding, particularly when it came to the significance of race and the legacy of slavery. As King powerfully points out, Arendt made “race thinking” central to her interpretation in The Origins of Totalitarianism yet avoided any discussion of the history of racism in the United States.

Rather than remaining in thrall to Arendt’s own theoretical categories King admirably examines how the ruling distinctions she developed most prominently in The Human Condition and On Revolution between the sphere of the “political” and that of the “social” hindered her assessment of some of the central events in the postwar United States. He argues that when she did turn her attention to civil rights and desegregation, for example, in her controversial essay “Reflections on Little Rock,” in which she rejected school desegregation as the public arena for resolving racial inequality, Arendt missed the extent to which radical politics in America were often related to religious and racial-ethnic experience—qualities that Arendt defined as part of the social rather than the political realm. By setting Arendt’s intervention in the context of the wider debates over desegregation, constitutionalism as well as the reception of her essay, King offers a critical perspective on her analysis from within her historical moment. He cites the author Ralph Ellison, who pointed out in a response to the publication of her essay that Arendt missed a crucial dimension of the event by failing to comprehend the perspective of the African American parents who were willing place their children at the center of the battle over civil rights.

The work also grapples with the tension between Arendt’s public statements and the opinions and attitudes that come across in her private correspondence. Though acknowledging that Arendt would have wanted to maintain a clear distinction between such statements, King asserts that it is the task of the intellectual historian to determine the relationship between them. Because he is particularly concerned with how Arendt arrived at her critical interpretations, King deems it valuable to interrogate the connection between her private utterances and the considered judgments that appear in her published work. For example, King unearths Arendt’s casual prejudice and use of racial epithets in describing of one of her black students in a letter to her husband Heinrich Blucher. In a characteristically self-reflective moment, King raises, “Are we just being prudish and politically naïve in squirming over the term she uses to refer to a young African student?”

Yet King also insists that it is ultimately productive for the historian to think with and against Arendt’s rigid categories and analytic distinctions, and not only to place them in their proper historical perspective. He argues, for example, that Arendt’s analysis in “Reflections on Little Rock” provokes a productive consideration of how to balance the recognition of difference with social and political equality though the essay itself failed to provide a satisfying formula. King also deftly fences with Arendt’s critics—both past and present—evaluating the status of their criticism when he revisits controversies like the melee over Eichmann in Jerusalem. Throughout the work King displays a sort of filial piety to Arendt’s critical legacy by demonstrating how the task of historical description and interpretation can coincide with historical judgment. Though he implies that at times such historical study would be better served without reference to Arendt, King ultimately affirms her continuing relevance in the pursuit of historical understanding.

[i] Judith Shklar, “Hannah Arendt’s Triumph,” New Republic

, December 27, 1975.

Mira Siegelberg is the Perkins-Cotsen Postdoctoral Fellow in the Princeton Society of Fellows and a lecturer in the Council of the Humanities and History. She is currently completing a book on the history of the concept of statelessness from the nineteenth century to the present day.

0