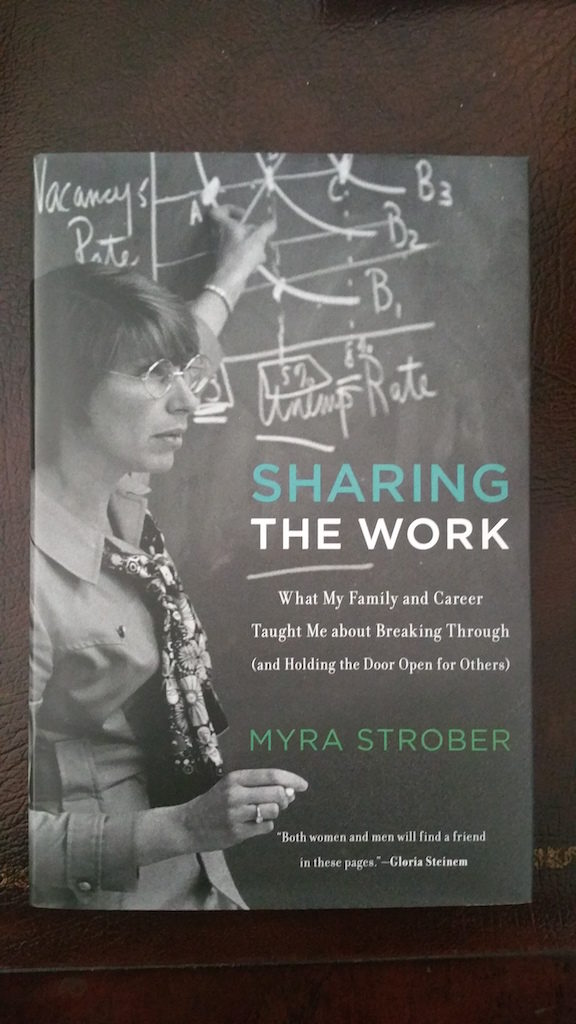

I just finished reading Myra Strober’s recently-published memoir, Sharing the Work: What My Family and Career Taught Me about Breaking Through (and Holding the Door Open for Others). Strober is a labor economist and a pioneer in the fields of both feminist economics and women’s/gender studies. A professor emerita at Stanford, she is the founding director of what is now the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University. (The institute, founded in 1974, was originally called the Center for Research on Women, or “CROW” – not the greatest acronym, Strober allows, but perhaps preferable to the alternative proposal: “Stanford Center for Research and Education of Women, or SCREW.”)

I just finished reading Myra Strober’s recently-published memoir, Sharing the Work: What My Family and Career Taught Me about Breaking Through (and Holding the Door Open for Others). Strober is a labor economist and a pioneer in the fields of both feminist economics and women’s/gender studies. A professor emerita at Stanford, she is the founding director of what is now the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University. (The institute, founded in 1974, was originally called the Center for Research on Women, or “CROW” – not the greatest acronym, Strober allows, but perhaps preferable to the alternative proposal: “Stanford Center for Research and Education of Women, or SCREW.”)

I found Strober’s memoir (which is a pleasant read) thanks to an adapted excerpt from it that ran last week in Times Higher Education. In the excerpt, Strober notes that in the early 1970s, only 5 percent of tenure-track faculty members at Stanford were women. From her memoir, I learn that by the early 1990s – just after the canon kerfuffle – a not-so-whopping 16 percent of tenure-track faculty were women.*

If you’ve read some of my past posts discussing my research

, you might wonder whether there were any women at all on the Stanford faculty in the 1970s or 1980s. I don’t recall that I have even mentioned a single woman professor who took part in the debates at Stanford – and there were several who did, whose contributions to the debate and its outcome were crucial. I certainly mentioned them in my dissertation, and I am expanding upon that research for the book. I’ll be presenting some of that work at our conference at Stanford this fall.

Strober’s lived experiences of the demographic disparities of the professoriate, and her career-long struggles to change those circumstances for herself and others, make for some compelling – and, for me, useful – reading. But the memoir – the memoir as a genre, and especially this memoir, I think – resists easy “academic” use. I have written elsewhere about how intellectual historians must “crack open” our sources, to some extent disregarding (or at least transgressing) “the ‘natural boundaries’ of texts that make them self-contained wholes.” But the memoir insists on presenting ideas not as detached or detachable from life but as inextricably embedded in it. Experience is the matrix of thought, not vice versa.

I use the word “matrix” purposefully here, though to what purpose I am not yet clear myself. Writing about the canon wars in and as gender(ed) history is the most difficult aspect of my work. Why? Well, I’d probably have to write a memoir to answer that question. So that question will have to wait. In the meantime, my working solution is the same as always: first pass around all the pieces of cake, then cut the cake; first write the history, then figure out how to write it. Life before thought – even for the life of the mind.

_____________

*Today, that number stands at around 26 percent, lower than the national average for doctoral and research universities, a still-underwhelming 33 percent.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

A follow-up post here — thinking about the glass ceiling of academe in the 1970s and 80s.

Look in Thy Glass