One cannot think of American history since the end of World War II without considering the importance of Muhammad Ali. He was, of course, one of the greatest boxers in the history of the sport. In the 20th

century it was often said that the heavyweight champion was one of the most recognizable people in the world. Ali definitely fit that bill in the Cold War-era world. Ali also transcended popular culture in a way few other athletes could. Considering that after his death Ali received tributes from sources as diverse as DC Comics fans and World Wrestling Entertainment, it is clear a wonderful book could—and should—be written about the massive impact Ali had on popular culture through the end of the 20th century and well into the 21st century. The era of Ali’s prominence, from the 1960s to the end of his life, could easily be called the “Age of Muhammad Ali.” But this essay wishes to reflect on Ali’s impact as a symbol—a symbol of African American strength and courage, and how that symbolism was transformed and, while being made universal, also weakened.

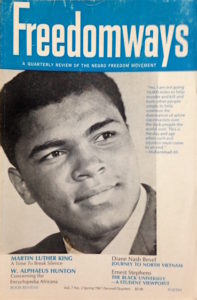

Muhammad Ali’s stance on the Vietnam War, friendship with Malcolm X (which tragically came to an end far too soon, before Malcolm’s assassination), his unabashed blackness during the Civil Rights and Black Power eras, and his solidarity with the Third World all made him a symbol to millions of African Americans. He especially inspired the African American Left, who time and again looked to Ali as the kind of mainstream tribune they could only dream up. Not only did Ali grace the covers of Ebony

, Jet, Time and Sports Illustrated, he also frequented the covers of Freedomways and Black World. His potency  as a symbol is one of the reasons his name will resonate for generations to come. This is not meant in any way to be hyperbole. When one thinks of the 1960s, what names come to mind? I would hazard a guess that Muhammad Ali would often find his way on a crowded list.

as a symbol is one of the reasons his name will resonate for generations to come. This is not meant in any way to be hyperbole. When one thinks of the 1960s, what names come to mind? I would hazard a guess that Muhammad Ali would often find his way on a crowded list.

Ali himself knew his place in the world. He used his celebrity to fight for causes he believed in—and, by losing the heavyweight championship in 1967 after refusing to answer his draft induction during the Vietnam War, demonstrated his willingness to put his livelihood on the line for what meant the most to him. The legacy of the African American athlete—someone often trapped between the riches and glory of sports, fame, and fortune, and a desire to do something for the rest of the African American community—was embodied in Ali.

The question must be asked, however, what it means when someone like Ali receives universal acclaim and praise at the time of his passing when, nearly fifty years ago, he was one of the most controversial figures in American society. As much as Ali symbolized a radical refusal of America’s war aims in Vietnam, he also represented other facets of the 1960s. His name change (from Cassius Clay, the name of a famed abolitionist and politician from Ali’s native Kentucky) struck a nerve with millions of Americans, white and black. Who was this man, no matter how athletically gifted, to dare to change his name? And to join the infamous Nation of Islam no less? And pal around with the dangerous Malcolm X?

His battles with Joe Frazier became a proxy for a nation divided along racial, cultural, and political lines. Ali’s fight with George Forman in Zaire in 1974 was symbolic of a Pan-African solidarity that vowed to have a fight in Africa, between two African American fighters, and promoted by African American Don King. Ali was controversial within the African American community as well, his membership in the Nation of Islam and the changing of his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali being points of debate among African Americans nationwide. In short, Ali was never a quiet figure, and even for African Americans at times he could be maddening and perplexing. But never boring.

It is also unmistakable to not that Ali transitioned from a radical political figure to a safe, warm, and beloved former athlete by all by the 1990s. No one in 1967 could have imagined Ali lighting the Olympic Torch 1996—and certainly not in Atlanta, Georgia. Yet, there he was, standing as a symbol of the goodness of American society. Ali’s shift in the public eye is unmistakable. Once he was a pariah for white America, while beloved among most African Americans as a symbol of resistance. American society has a knack of absorbing figures once derided as too radical or too black and making them into all-American heroes. Martin Luther King, Jr. and to a lesser extent Malcolm X come to mind. Ali’s change in the public eye was different from those two because (thankfully) he was not assassinated. Thus, he lived through the end of Black Power, the rise of conservative backlash, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Ali’s life, therefore, coincided with the lowest moment of American confidence during the post-1945 years—the combination of Watergate and defeat in Vietnam—along with its post-Cold War, Pax Americana high of the mid-1990s. His lighting of the Olympic Torch in 1996 was a symbol of that patriotic fervor.

Yet the Left, and especially the African American Left, never forgot about Ali’s stances on the major political issues of the 1960s and 1970s. For them, he was also a symbol. As the editors of Freedomways wrote, at the height of Ali’s battle against being inducted into the U.S. Army, “In taking his stand as a matter of conscience, the world heavyweight champion may be giving up a small fortune, but he has undoubtedly gained the respect and admiration of a very large part of humanity. That, after all, is the measure of a Man.”[1]

The price paid forgetting Ali the historical figure—complicated, flawed, as human as the rest of us—is the same price our society has paid when any historical figure enters the pantheon of American civil religion. There, figures from the past become heroes of the present, and guiding lights for the future. Ali will be no different. His “entry” into American civil religion, and away from controversy, means that historians will have to work all the harder to make sure the complicated and human figure of Muhammad Ali is not lost in  favor of an Ali whose stance on Vietnam is not forgotten as the controversial and divisive stance that it was at the time. No one truly knows who is on the “right” side of history. Ali certainly did not think about that in 1967. He instead worried more about his conscience, and his belief in standing against a war he believed was unjust for numerous reasons.

favor of an Ali whose stance on Vietnam is not forgotten as the controversial and divisive stance that it was at the time. No one truly knows who is on the “right” side of history. Ali certainly did not think about that in 1967. He instead worried more about his conscience, and his belief in standing against a war he believed was unjust for numerous reasons.

I find myself thinking about another African American man whose obituary I also wrote for this blog less than a year ago: Julian Bond. Ali and Bond both came of age during the 1960s. They both stood up to be counted against the Vietnam War—and both paid the price for that. And both men lived long enough to see a changing American society. It was one that benefited from the work both of them did, but also continued to experience problems with racism and militarism that both Ali and Bond worked so hard against. Ali and Bond died as the country continued to face these long-standing problems with half-hearted effort.

America has not fully reconciled itself with anti-black racism. Nor has it fully come to terms with the Vietnam War. And the uptick in anti-Islam sentiment in American society means that, too, is a burden we shall all have to deal with. Muhammad Ali, as a living, breathing man, forced American society to deal with these problems. I can only hope in death we all—historians, scholars, citizens—continue to grapple with his life and legacy fairly and critically. When a figure like Ali is memorialized with near-universal tributes of praise, it is time for the historian to breathe deeply, think critically, and do the hard work of writing and talking about a human being who inspired so many—precisely because he was willing to anger so many others for causes much greater than himself. The Age of Muhammad Ali that we were all privileged to live in has ended. Now begins the hard work of thinking about what that era meant for America, and the world.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Insightful! Ali’s death might be the kind of feint to subdue the American society’s anti-Islam uptick that you point out.

Robert: Thanks so much for the post and reflection. In line with taking a step back and thinking critically, and marshaling the work of Warren Susman, I think that the wide adulation of Ali stems more from his celebrity than his life. As Susman noted many years ago, there seems to be a tendency in U.S. culture, for better or for worse, to care more about “personality” than character. Or, as Daniel Boorstin put it (in The Image, 1971), we celebrate “larger-than-life” heroes, “celebrity-personalities,” and their “well-knownness.” You might say that Ali suffered from his celebrity even as his more substantial character traits were, well, ignored or forgotten later. – TL

This is a wonderful point. Susman’s analysis of celebrity culture in American society makes perfect sense in this context.