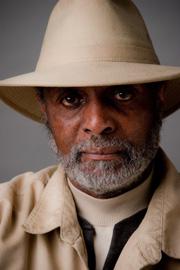

Last week the academic community was stunned to hear of the passing of famed scholar Cedric Robinson. A professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Robinson shaped the careers of dozens of academics and intellectuals through his books and lectures. While each of his books was a major contribution to thinking about the African American experience, his magnum opus Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983), more than any other set the stage for the next thirty years of thinking about radicalism among people of African descent in the West. It is no exaggeration to say that few works have had more of an influence on intellectual history, cultural studies, and African American Studies than this one.

I have been moved by the tributes written to Robinson at the African American Intellectual History Society over the last week. They capture Robinson’s importance as both a scholar to the wider intellectual community, and as a mentor to numerous graduate students. For me, Black Marxism has time and again forced me to think about African American, and American, intellectual history in a much broader context. Robinson not only told a story about the central tenets of “the black radical tradition,” he also sketched a much broader history of the West itself. Race, nationalism, and different kinds of radicalism form the heart of Black Marxism. In the process, Robinson’s tome has allowed scholars to think of  Marxism from multiple critical angles. After all, if one questions the validity of the vision of Marx and Engels from a historical standpoint, with race and nationalism firmly at the center of that critique, it opens up other avenues of criticism—including gender and sexual orientation—from which to interrogate the idea of Marxism and western radicalism more broadly.

Marxism from multiple critical angles. After all, if one questions the validity of the vision of Marx and Engels from a historical standpoint, with race and nationalism firmly at the center of that critique, it opens up other avenues of criticism—including gender and sexual orientation—from which to interrogate the idea of Marxism and western radicalism more broadly.

Black Marxism should be required reading for anyone who studies American intellectual history—especially (but certainly not only) scholars who specialize in 20th century intellectual history. Robinson’s reappraisal of W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, and Richard Wright near the end of his book are important intellectual biographies of those important intellectuals. Robinson’s “Historiography and the Black Radical Tradition,” by itself, constitutes a tour de force in analyzing both the American Left of the first half of the 20th

century, and understanding how history as a profession has long been an intellectual battleground for African American scholars. Robinson’s clarity when discussing the contours of the Black Diaspora, and its intellectual legacy, are to be envied.

There is much I am leaving out when it comes to Black Marxism. I can only state, once again, how essential a book it is to any scholar of intellectual history. Andrew Hartman and  I discussed the book some time ago on Facebook, leading to this illuminating and thought-provoking post by Dr. Hartman here at S-USIH. The post also led to Dr. Hartman and I discussing a potential panel for a conference about Black Marxism. I looked forward to personally emailing Cedric Robinson to ask him to join our panel.

I discussed the book some time ago on Facebook, leading to this illuminating and thought-provoking post by Dr. Hartman here at S-USIH. The post also led to Dr. Hartman and I discussing a potential panel for a conference about Black Marxism. I looked forward to personally emailing Cedric Robinson to ask him to join our panel.

Unfortunately, I learned of his death right before I could contact him. I never had the distinct honor of telling him how much his work meant to me. His death has, frankly, hit me as hard as the death of Vincent Harding two years ago. Both scholars shaped my work in history in ways that are nearly beyond description. From both Harding and Robinson I learned the importance of history to our society, the ways in which history can keep alive the heart and soul of the African American community in the face of implacable opposition. From both scholars I gained an understanding of what it means to be a dedicated scholar. In no way can I say I am an equal of Harding or Robinson. I doubt I can ever say that. Their work has never been timelier than it is now, with radical movements across the United States once again making previously ignored voices heard. But, I suspect, they both would want me to continue the work of a scholar, a thinker, with good cheer, a humble attitude, and a dedication to work on behalf many others who have not had the same access to the academy I have been lucky to gain.

The academic community is poorer without Cedric Robinson here with us. But the work goes on, and we owe it to him—and so many other scholars—to put forth our best effort as historians, scholars, and citizens of the world.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks, Robert, for calling attention to Cedric Robinson’s death and also reminding us of Vincent Harding’s death not long ago. Both figures deserve more attention from historians of African American thought and culture and more rigorous and analytical attention paid to their work. By including James with DuBois and Wright, Cedric Robinson already anticipated the essential truth of Paul Gilroy’s “Black Atlantic” thesis–national boundaries are highly artificial things when it comes to understanding the history of any tradition of thought but particularly that of the Black Diaspora

All very true–when I was re-reading “Black Marxism” this weekend, I was struck by how Robin D.G. Kelley in his forward made the same point. Thanks, as always, for the kind words.

Robert, I echo Richard King’s gratitude to you for the beautiful tribute you wrote for the late Dr Robinson…Having studied with him closely when i was in the UCSB PhD program, I can testify that my time in his presence was nothing short of enlightening and inspiring. Dr Robinson was one beautiful Cat! Rest In Power, Professor!