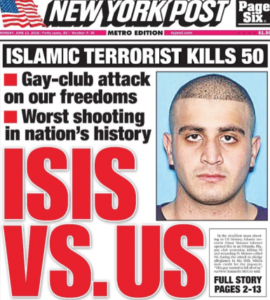

To a very great extent, this past week has been dominated by discussions of the Orlando nightclub shooting. When the scale of that attack became clear, media outlets nearly universally declared that it was the “worst massacre in American history.” Very quickly, historians, among others, responded by pointing to many events in American history in which more people were killed: the Tulsa Race Riot, Wounded Knee, the bombing of the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City, the Happy Land fire in the Bronx, and many more. Somewhat more quietly there has been a pushback against these pieces online. “When comparing tragedies, nobody wins,” blogged the gay, Native American artist Fox Spears.

To a very great extent, this past week has been dominated by discussions of the Orlando nightclub shooting. When the scale of that attack became clear, media outlets nearly universally declared that it was the “worst massacre in American history.” Very quickly, historians, among others, responded by pointing to many events in American history in which more people were killed: the Tulsa Race Riot, Wounded Knee, the bombing of the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City, the Happy Land fire in the Bronx, and many more. Somewhat more quietly there has been a pushback against these pieces online. “When comparing tragedies, nobody wins,” blogged the gay, Native American artist Fox Spears.

There is, on the face of it, something unseemly about counting bodies and giving some event the title of “most deadly” or “worst.” But as with any event in history, part of understanding the Orlando shooting necessarily involves comparing it to other similar events…and even arguing about what those other similar events might be. A particularly pointed example of such an argument took place on Britain’s Sky News, Rupert Murdoch’s cable news operation in that country. The columnist Owen Jones walked off set in the middle of a discussion of the shootings when the other two people with whom he was appearing repeatedly refused to accept that this was in any particular sense an attack on LGBT people. As Jones pointed out before eventually giving up and leaving, if there were a mass shooting in a synagogue, nobody would hesitate to call it antisemitic.

Those who’ve pointed to other, larger massacres – and much of this discussion implicitly has to do with the slipperiness of that term – have not, I think, done so to minimize the Orlando shootings, but rather to suggest that, far from being the sudden, unusual arrival of an essentially foreign threat on American soil, as Donald Trump, in particular, has suggested, the Orlando shootings fit into a much broader history of American violence.[1]

Of course, like any other event, the Orlando shootings took place in multiple relevant contexts. a fact reflected in the wide range of conversations that are being had about this event. American gun laws, ISIS, homophobia, gay self-loathing, mental health, domestic abuse, immigration, Islam, and toxic masculinity are among the many frames that have, rightly or wrongly, defined the ongoing national discussions of the killings.

Today happens to be the one-year anniversary of another massacre, the Charleston church shooting. One of the remarkable things about the aftermath of that awful event was the extent to which a consensus quickly emerged in American public culture that the most important context for understanding that shooting was the legacy of white supremacy. Within a month, even South Carolina’s Republican Governor Nikki Haley was calling for the confederate flag to be removed from the statehouse grounds.

It’s anybody’s guess what the dominant understanding of the Orlando shootings will be in a year, five years, or a century from now. Presumably our understanding will reflect any new information that we may find out about the shooter and his motives in the coming days and weeks. But one way or another, a well-grounded understanding of this event will involve comparing it to other acts of violence.

_____________________________________

Even Hillary Clinton, it should be said, has presented ISIS as the single most significant context for the shootings. In remarks this Monday

, Clinton promised, if elected President, to focus on stopping “lone wolf” terrorists like the Orlando shooter. “The Orlando terrorist may be dead, but the virus that poisoned his mind remains very much alive,” she declared. And that “virus” is connected with “the barbarity we face from radical jihadists.”

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

A very interesting read, but…

I don’t mean to be a buzz-kill, but you overlooked the two biggest examples in American history that resulted in the most people killed. Though many people, especially European-Americans don’t want to hear about these two – they did happen. And, as an African-American with long, family acknowledged Native-American ancestry, I feel it an important, contextual point.

Though mostly unintentional, smallpox and other ‘Old World’ microbes decimated Native Americans. Most others done in by Governmental Indian Agents, cowboys and assholes taking umbrage at ‘Indians’ actually fighting against European Conquistadors taking over their land. The total death toll during that time, from 1492 until, I would say, the late 1800’s when Manifest Destiny was all but completed was never documented. My learning is, roughly, 60 million lost their lives, though that number is very debatable.

The other, as you might expect, is Slavery. Though not a singular American endeavor, certainly there were European and African accomplices, but the transatlantic slave trade resulted in millions of deaths through procurement, adjusting ship ballast and the thinking at the time that Africans were subhuman and therefore disposable. But the United States can take all the credit for the institution of generational, racial slavery in North America and the well-known associated atrocities. The number of total deaths are nebulous to say the least, but I feel safe in saying it’s in the tens of millions.

Your piece was comparing more contemporary events, and I understand that, but the sheer scale of these two American tragedies, at least as viewed by African-Americans and Native Americans, deserved, I thought, an honorable (dishonorable?) mention.

Hope I haven’t been too wordy.

Ben, thank you, as always, for an excellent provocation. I don’t want to dilute the importance or emotional content of these shootings, but perhaps fit them into an even larger context. I was just having similar thoughts last week about the impending nomination of Hillary Clinton, as my Facebook feed was filled with posts celebrating “The first woman ever to run for the US presidency.”

To which the “gotcha” culture of Facebooklandia replied, “Oh yeah? Shirley Chisholm BOOM MIC DROP”

To which I replied until I got tired of it, “Oh yeah? Victoria Woodhull BOOM MIC DROP”

Snark aside, I think that it’s worth asking why we measure the significance of an event in its being the first or the biggest or the worst. Will Clinton’s nomination be less significant if it’s not the first of its kind? Will Orlando be less horrific if it’s not the worst thing ever? I’m reminded of the hyperbole my undergrads engage in when they evaluate my classes with comments like “Best teacher ever!” or “Worst class EVAR!!1!” How do superlatives convey something that prosaic descriptions do not?

I’m with you, Scott, on the question about the need for superlatives. Is this a Joseph Campbell-esque drive for heroes? – TL

“First” things are very often overrated, overly denigrated, and overly celebrated. Almost always, the purported “first” was not in fact the first. The person designated as a “first” often enjoys unwarranted praise or denigration due to the purported accomplishment. But of course I think this way because I’ve spent a lot of time, like most readers here, thinking about purported precedents and/or unprecedented events and actions. So-called foundational firsts always seem to have more turtles underneath them. – TL