Last month, I had the honor of being published, along with dozens of wonderful scholars, in an essay collection called Keywords for Radicals. The volume is intended to continue the work of Raymond Williams’ Keywords, updating it in light of new political realities impossible to foresee in 1976. Or, as the subtitle puts it, the book explores “The Contested Vocabulary of Late-Capitalist Struggle.”

As the editors (Kelly Fritsch, Clare O’Connor, and AK Thompson) explain in the introduction, this latest continuation of Williams’ project aims to excavate the contours and contradictions of our contemporary political moment by discovering how “keywords” have changed up to the present moment. By doing so, the objective is not to settle upon an official definition, but rather to gain a better understanding of where we stand so that we may more knowledgably try to move forward. As they write, “In this way, we hope to devise an analysis of the social world that coincides with the conflicts we uncover in our most intimate utterances. Rather than facilitating communication by proposing an agreed-upon lexicon, our goal is to hasten its ‘brittle’ degeneration so that a new reality and a new understanding might emerge.”[1]

My contribution to the collection is an entry on the term “Liberal.” Although I begin with its earliest forms, the majority of the essay concerns the shifting fate of the term – from a radical perspective, that is – in the last half-century or so of American history. Ultimately, I conclude that the most useful meaning (again, for radicals) of the word is one of clarifying negative definition; as I write, “Liberalism, as a political philosophy committed to capitalism, is what radicalism is not.”[2] That’s all I am going to say about my piece here, but by all means, feel free to buy the book if you want to read more!

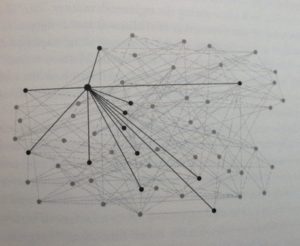

However, I do want to reflect a little on how my “keyword” connects to the broader project. One of the most delightful things about this new volume of “keywords” are the visual maps that accompany each chapter, illustrating how each term connects to and invokes others that intertwine with its own meanings and uses.[3] Such related keywords are listed, then, at the end of each entry, so a reader could decide, if they wish, to go on a kind of “choose your own adventure” journey through the text, bouncing around from association or overlapping idea to the next. Here, for example, is the network map for my essay, with the terms each dot represents listed below:

See Also: Agency; Authority; Class; Democracy; Friend; Ideology; Nation; Politics; Populism; Race; Responsibility; Rights

Such visual mapping of abstract ideas is a relatively new and exciting way to grapple with the edifice of ideas that intellectual historians often consider their bread and butter. Yet in the context of recent political news, I realized that such a metaphor for how ideas function in relation to one another can be as terrifying as it is clarifying. Staring into the crisscrossing lines of the vocabulary of struggle, these patterns begin to look less like a map, and more like a net we’re trapped in and can’t untangle. While it is not at all surprising that Gramsci is frequently mentioned in Keywords, at times I cannot help feeling that rather than warriors skillfully deactivating traps while navigating through a booby-trapped battlefield of position, we on the left resemble more an endangered dolphin thrashing desperately to free itself from a net, splashing with terror while the fishing line knots its way around its flippers and cuts into its flesh.

Consider the word I was tasked with unpacking, for example. “Liberal” is actually one of the less vague and capacious terms the book tackles, which includes entries for concepts like “love” and “friendship.” And yet in my current historical context – early twenty-first century America – I can’t even casually employ this term without confusing the majority of people around me. I’m not talking about debates over what is the liberal in neoliberal, or whether or not liberal “freedom” has always been predicated on the oppression of others, but simply how say, someone sitting in a coffee shop next to me might interpret it if I made a snarky joke about liberals. Without further information, they’re very likely to think I am a conservative, because our political culture is so center-right, that the entire idea that I might be mocking liberals or liberalism from a position on the left will not immediately occur to most people.

So, I ask, how bad are things when this is how far we are from having a vocabulary to even begin working with, when so many of our terms mean something different to us than others that we don’t even know what words to use to deconstruct the predominant discourse? Liberal piety will talk about “having a conversation” or coming to “civil understanding,” but what that misses – and what indeed, almost every single American pundit missed when assuring the nation that Americans would never select someone like Trump as a major presidential candidate – is that there is little to no common ground on which to even begin such a “conversation.” Reading the summary of the recent conference entirely predicated on disputing this, for example, I found myself wondering what, exactly, this supposed common ground actually consists of – the discussion seemed so broad, vague and conceptual that almost nothing specific in terms of policy or preference seemed to appear (although we did all learn that feminism partakes in a culture of death, so, that’s great). If this is our common ground, I have to say it seems to me that it’s located mostly in the clouds.

Except for one thing. The younger folks – all screeching about Millennials aside – might actually be ok. I hesitate to put much stock in the idea that all we have to do is wait for these social democracy enthusiasts to get into positions of power, because the politics of a generation are always subject to change – and who knows how much change they are up for, really – but still: the sudden dissemination of the word “socialism” has got to mean something, and I can’t help but feel that it means something good. That’s why the publication of Keywords for Radicals is so appropriate for the moment we are living in, and as I read through all the brilliant entries while contemplating the possibly increasing audience they will seem relevant to, I feel proud, rather than pessimistic, about how far the global left has come in the last half-century. Keywords for Radicals is not only a map of the present or a primer for the future, but it is also a critical self-reflection that lays bare what, even while thrashing around in that net of neoliberalism, we’ve managed to learn and create. And so while I work myself out of post-Indiana-primary despair, I’m going to keep on reading these amazing entries, for so many of these terms to think through are also words to hope with.[4]

[1] Editors Kelly Fritsch, Clare O’Connor, and AK Thompson, Keywords for Radicals: The Contested Vocabulary of Late-Capitalist Struggle (Chico: AK Press, 2016), 18.

[2] Robin Marie Averbeck, “Liberal,” in Keywords for Radicals,

243.

[3] This is only one aspect of a book which is, I would like to note, absolutely beautifully put together. From the cover, to the font choice, to the layout, everything is perfect. As someone who takes the aesthetics of books very seriously, I would like to extend my heartfelt thank you to the people who created the design.

[4] Interestingly enough, “hope” itself is a term in Keywords for Radicals, where the main fault line appears to lie between those who see hope as a revolutionary force, and those who see it as a tool of those in power (Ana Cecilia Dinerstein, “Hope,” in Keywords for Radicals, 199-205).

0