The following guest post is by James Perosi-Doughty, Université Bordeaux Montaigne: Culture et littératures des mondes anglophones (CLIMAS).

The year 2001 holds various degrees of significance depending on the context or the person asked. It was the official start of not only the 21st century, but also of a new millennium; a millennium that was to be the promise of hope and new beginnings. By all literary and cinematographic accounts, mankind was supposed to have flying cars and Space Odysseys. Of course, it was none of those things. If anything, the start of the new millennium made mankind, especially Americans aware of the limits of their beliefs, power, and more importantly, their security.

The year 2001 holds various degrees of significance depending on the context or the person asked. It was the official start of not only the 21st century, but also of a new millennium; a millennium that was to be the promise of hope and new beginnings. By all literary and cinematographic accounts, mankind was supposed to have flying cars and Space Odysseys. Of course, it was none of those things. If anything, the start of the new millennium made mankind, especially Americans aware of the limits of their beliefs, power, and more importantly, their security.

There are no words to sum up or to accurately describe the gamut of emotions linked with September 11th, 2001. Americans, and to a certain extent, the rest of the world realized how dangerous the new millennium actually was. What was perhaps more frightening, was the feeling that this attack represented a “new type” of enemy (“Terrorist Attacks” infoplease.com) (1); it certainly was a non-traditional enemy. What was certain, was that the days of September 10th and before were over. The United States, and by consequence, the world had entered into a Post 9/11 era, where common methods of travel were constantly screened to maintain vigilance; a world where safety was color-coded (Schwartz 2014, nytimes.com) (2) ; a world where everyday items were seen as potential threats (“Traveler Info” tsa.gov

).

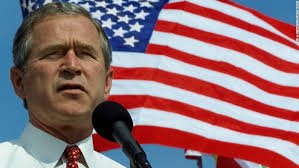

Perhaps no man embodied, for better or worse this changing world and new attitudes for approaching security threats, than the 43rd President of the United States: George W. Bush. An extremely interesting political figure domestically as well as internationally (“Global Public” 2008, pewglobal.org) (3), Bush’s worldview ultimately shaped the first decade of the new millennium, leaving a mark not only on American but world history, thus carrying consequences which scholars are still discussing.

The scars left on George Bush’s America can certainly be defined in many ways. They could be defined as tragic of course, due to the events of September 11th, and to a certain degree the still-unfolding consequences of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, ISIS for example. Another way to understand these scars is to view through the lens of irony, specifically, the irony that Reinhold Niebuhr discussed throughout his career and had made famous in his works. However, before delving into the complexity of Niebuhr’s irony, a more detailed analysis of his life and work is needed in order to better understand his own vision of the world.

It is because of these lasting scars that looking at Bush’s policies through a Niebuhrian understanding merits attention. Niebuhr’s Christian realism brings a notion of morality to politics without drowning in idealism or self-delusion. Given the rapidly changing environment of international affairs, looking at this environment through a more realistic lens is not only interesting, but almost required. Thus, the pertinence of this topic is to demonstrate how blind faith and total self-assurance from leaders not only ignores the harsh realities of power politics and the natural pursuit of self-interest found within humanity, it also leads to dangerous and unknowable consequences that can take decades to resolve. A Niebuhrian analysis of Bush’s policies, which have better or worse shaped the first part of 21st-century America, can unveil the weaknesses in Bush’s policies, ultimately looking at resolving some of the various unforeseen consequences that Bush’s actions and policies placed upon the United States. Before delving into this however, it is important to give some background information on Niebuhr and his philosophy.

Niebuhr was extremely influential throughout the early part of the 20th century, notably during the two world wars. Trained as minister, Niebuhr eventually developed a political philosophy based upon his religious upbringing. This philosophy would later become known as Christian realism. Niebuhr’s religiously influenced political philosophy was not as contradictory as it first appears because of how he and his family had viewed the Christian faith. As Niebuhrien historian Richard Fox states regarding the Niebuhr household’s religious point of view: “[The family] was both liberal and evangelical in their faith. [The father] was liberal in his convictions that the Gospel was social as well as individual and that the Christian had to work for social improvements and not simply for religious conversions” (7). This approach was firmly held by Niebuhr’s father and was taught onto Reinhold, largely shaping his political and religious views.

Though Reinhold held onto several firm beliefs of his family, one of the things he developed independently was the need and use of religion in everyday life. As opposed to a philosophical approach on how the Christian faith could bring about peace, enlightenment, and ultimately salvation, Niebuhr felt “the certitude of religion could no longer be based on “extra-human revelations,” it had to be founded on a philosophy of human needs, and in real experiences in faith […]. [H]uman beings needed two things: assurance that a “divine” had a place in the universe which was apparently impersonal and the assurance of personal contact with this eternal standard” (Fox 30). This meant that Christianity had to be a “social” or involved movement where improvement on a societal level was desired rather than individual salvation. There were real problems in the world that needed to be addressed, and a “good” Christian according to Niebuhr was one that was involved.

This type of “chrétien engagé” meant that Niebuhr felt a responsibility towards the events which unfolded around him. Niebuhr, having lived through some of the most tumultuous events in 20th-century western history, had much to talk about including the two world wars and the Cold War. Modern warfare of contemporary states turned loyalty and courage into supreme values “without any thought” to the means used to achieve their ends. The First World War revealed the paradox of the soldier. He developed this paradox in his article “The Nation’s Crime Against the Individual.” In this essay, Niebuhr stated that by turning courage and loyalty into the supreme value for the soldier, the modern state ended up destroying former ties to a Church, to a religion, or to a social class. The paradox being that as soon as the soldier was sent, the State could do nothing to honor the soldier but to proclaim how the soldier’s sacrifice had contributed to the prosperity of the nation (Fox 46). In the article, Niebuhr states that “the crime of the State against the individual is not that it asks him to sacrifice himself against his will, but that the state claims a life of eternal significance for ends which don’t have eternal value” (qtd. in Fox 47).

His criticisms towards the modern nation-state were augmented due to the disillusionment exposed by failed Wilsonian policies, most notable: the disasters of the League of Nations and the general pettiness of the Treaty of Versailles as well as the problems he saw with economic inequality in the US. The Treaty was, “inspired by a desire for revenge, rather than for settling the foundations of peace or the ideals of brotherhood” (Holder 9). He felt that the liberal values of Wilson and the goals of the League of Nations had been circumvented by the realities of post-war politics. Internationally, he noticed how after the war, in America as in England, there was a sharp return to right-wing conservatism and a perversion of patriotism.

Furthermore, the Treaty of Versailles demonstrated the harsh realities of human nature. Where Wilson had hoped that the pursuit of self-interest, economic prosperity, and “more democracy” would ensure that the Great War was truly the “war to end all wars,” the realities of post-war politics quickly demonstrated the naiveté of such a vision. According to Niebuhr, the Treaty of Versailles demonstrated the sheer pettiness of peoples, in this instant the French towards the Germans. Similarly, the fact that the United States, the “mastermind” behind the League, refused to sign the charter as it would place foreign powers ahead of national sovereignty, only highlighted the inherent selfishness of humanity.

Domestically, Niebuhr heavily criticized Henry Ford, his automobile empire, and the growing materialism and inequality gap he saw in America. Based in Detroit for his congregation, he saw firsthand how Ford was able to make a profit at the expense of the worker, all the while using a strong public-relations arm to promote the idea that he was helping workers and the US economy. Niebuhr was very critical of Ford for various reasons, but they all come down to the idea that “History ought to have taught us that the man who holds power is never as benevolent as he imagines himself to be” (“Henry Ford and Industrial Autocracy” 1355). Niebuhr leveled three major critiques (4) against Ford and his motor empire: 1) Ford was not as civic minded as he claimed. His main purpose was to run a business and his business ran as an autocracy. Though not necessarily critical of this fact as it was common in American business, Niebuhr found the major fault to be how Ford was promoting the idea that he ran his business differently, and was critical of America for buying into this romantic and unrealistic vision. 2) Ford’s refusal to offer unemployment insurance to his workers. Again, this was common practice at the time, but Niebuhr felt due to the higher percentage of Detroit citizens who were working for Ford, the city, and thus its workers, were disproportionately affected by massive layoffs or other major company policies. 3) Finally, Niebuhr criticized Ford, but also the American people for buying into the notion that workers were nothing more than machines, to be used and treated as such (Holder 27-29). All of these factors made Niebuhr realize that he was no longer the liberal who had hoped that democracy could change the world. He realized how complicated real-world politics were, especially in matters of foreign policy. He had become someone with a more realistic and sober vision of reality.

Nevertheless, Niebuhr never truly became cynical in his worldview. His idealism was replaced with a more realistic point of view on human nature. He kept a Christian undertone, hence the philosophy of “Christian realism.” For Niebuhr, the idea that “man is good” didn’t reflect reality. If humanity was so good, why then did World War I happen? Why were the Jews suffering in Europe, and why was there such racial prejudice in the US? In Niebuhr’s eyes, modernity wanted to “glorify individual liberty” all while ignoring any of the negative consequences that extreme versions of this freedom could bring about (Fox 179). This was because, for Niebuhr, humanity’s greatest sin was that a person could not accept his/her own limits. “Man is mortal. This is his destiny. Man pretends that he is not mortal. This is his sin” (Fox 181). Pride, for Niebuhr, was man’s ultimate sin and greatest problem. Pride was demonstrated through humanity’s belief that it could not only dominate nature but could equally control its destiny through controlling History.

Though man sinned, Niebuhr never held a tragic view of man’s place in the world, nor did he ever consider himself a classic realist. In his collection of essays, Beyond Tragedy, Niebuhr tried to prove how Protestant Christianity was the only analysis of man and history which was actually positive. “The opinions of Christians towards history is tragic in the measure where it acknowledges evil as an inevitable event of the most noble and spiritual actions. It goes beyond tragedy in the measure that it does not consider evil as something which exists independently but as something under the dominion of a good God”(qtd. in Fox 182). Therefore, the good Christian didn’t complain about his destiny, he took responsibility for it.

This sense of responsibility brought Niebuhr to lead the battle for American intervention in Europe during World War II. This was a split from his earlier years, as well as the pacifists of his time who were still keeping to their ideals. Niebuhr broke from this, stating that a good “Christian realist” acknowledges that certain evils in the world, in this case, Hitler, cannot be bargained with. For the Christian realist, there can be morality in politics depending on the leader in question, especially when it comes to foreign policy, and especially with clearly defined evils such as Hitler. America for Niebuhr did hold a special place in the world, and it was because of this unique position, that America had a responsibility towards liberating Europe from fascist regimes (Fox 199).

It wasn’t until the end of World War II, the bombings in Japan, and the rise of the USSR that Niebuhr realized the irony of the American situation. According to Niebuhr, “Americans weren’t the simple victims of their history. They helped achieve it, they carried the responsibility for it; it wasn’t just a series of natural events” (Fox 245). American history, and consequently its future, was ironic because everything depended on the choice of Americans, and not on actions beyond their control. Niebuhr’s choice in analyzing American history through irony was a pivotal moment in Niebuhr’s career and philosophical development, thus, further analysis and development into Niebuhrien irony is needed.

Niebuhr chose irony and loved the concept of irony because he associated it with God. God was the ultimate judge of humanity, and although He was a judge filled with righteous anger as seen in the Old Testament, in the New Testament, Niebuhr saw a God not simply a damning God, but also one who was the supreme redeemer and forgiver, looking down with a knowing smile. This was how Niebuhr saw America and American politics. He felt that America took itself too seriously, and thought itself too important. For Americans, the United States was beyond the control or confines of History, thus falling into the sin of all men and nations: pride. Therefore, towards the end of his life and career, Niebuhr became critical of American policy, both foreign and domestic, not because he was “anti-American,” but because he felt that the role of the Christian Realist was that of the Prophet: a figure to keep its leaders and the State’s pride in check as to not bring down the wrath of God.

Christian realism depended heavily on irony. However, Niebuhr’s use of irony is neither the classic nor literary sense of the word; rather it takes on a definition similar to that of a paradox. In his classic work on foreign policy, The Irony of American History, Niebuhr stresses that American history, and thus any analysis of foreign policy, must be viewed from an ironic lens, rather than from a pathetic (pathos) or tragic lens. For Niebuhr, American history is neither pathetic nor tragic because “[…] pathos is that element in a historic situation which elicits pity, but neither deserves admiration nor warrants contrition […] The tragic element in a human situation is constituted of conscious choices of evil for the sake of good.” (xxiii). An ironic situation for Niebuhr is one in which the actor bears some responsibility for the situation he may find himself in, thus distinguishing it from pathos where events simply happen without any control. Similarly, this situation differs from tragedy in that the actor’s response requiring any questionable or evil means is linked to an inner weakness or lack of self-understanding rather than a conscious decision of the “ends justifying the means.” Added to his analysis is a sense of ironic humor in America’s situation, again largely due to his religious belief that God is not only the supreme judge but also the divine redeemer; capable of simultaneously judging and laughing at man’s inability to see his own limits.

Niebuhr’s irony stems of course, from his religious beliefs, and more specifically, his understanding of the world as a Christian. Throughout his life, he analyzed the paradox of Christian life: trying to incorporate the Christian ideal of love or agape, which was by definition individualistic, with the social ideal of justice, which deals with seeking to blend common interests together. “Love was the highest ideal for the individual, but justice was the maximum goal of the society” (Holder 34). Thus, Niebuhr saw the world and foreign policy through this paradoxical lens of two competing interests that had to be brought together. Continuing on the paradoxical analysis of society, Niebuhr’s understanding of human nature was dualistic and seemingly contradictory.

During his time, Niebuhr summarized three basic understandings of human nature and its relation to the world: classical, biblical and modern (Holder 34). The classical view was that of Man differing from other animals through his capacity to reason. Niebuhr’s primary critique against this dualistic approach was how it negatively viewed the physical form of man, his needs, and his desires. By ignoring, denying, or flat out sullying the physical human form was to ignore the entirety of the human experience and its relation to history (Holder 33).

Though the classical view of human nature had many a fault, it paled in comparison to the naive and dangerously erroneous modern understanding of human nature which was held by his contemporaries. “For Niebuhr, the modern view of humanity was an amalgam of the worst feature of the classical view – its materialism – with the freedom of the Renaissance and a strong tinge of the romantic that exalted the “natural” state of human embodiment and emotion” (Holder 34). It was basically a combination of the two worst factors in understanding human nature: an obsession with things (materialism) with the naive view of the “natural man” (that he is ultimately good). For Niebuhr, this combination of philosophies showed a complete misunderstanding of human history. History and society were proving modernity wrong. Man is not

inherently good and progress shouldn’t always be associated with materialism.

Only through a biblical understanding of human nature and history, could man truly understand his place in the world and ultimately history. It shouldn’t be surprising that Niebuhr favored this approach to the classical or modern counterparts when discussing human nature, given his deeply held religious beliefs. It was the biblical approach best expressed in his works such as The Nature and Destiny of Man Vol I & II or Faith and History, according to Niebuhr, that resolved, at least partially, the paradox that is human existence. It was only through the biblical view which “respected both humanity’s limitations and transcendent qualities” (Holder 34). Man is finite because he is physical, but he is able to partially obtain infinity through the ability of self-transcendence, but only when he admits his own finiteness. This is the paradox of the human condition (Holder 34). It is this relationship, that man is both limited by his physical mortality, yet unlimited by his ability to partially attain infinity through God’s Grace, which gives man his uniqueness: the ability for greatness, for freedom, but also for evil. This paradox of being both finite and free, leads man to its greatest sin (5) : pride.

The sin of pride stems from man’s understanding of how finite and limited he is, causing him severe anxiety about his place in the universe. Thus, this combination of self-limitation and anxiety leads man to the sin because he tries overcome his finiteness through rebellion against the natural order and God’s will; or in other words, try to make himself important enough to control or shape history. In a Niebuhrien understanding of Christianity, man is truly free, but this freedom is ultimately used to try to surpass man’s finiteness.

The paradox of freedom/sin led Niebuhr to see, and more importantly, understand the world through the lens of irony. As discussed earlier, Niebuhr’s use of irony was very specific and though similar to tragedy, it was decidedly different. For Niebuhr, irony was “apparently fortuitous incongruities in life which are discovered, upon closer examination, to be not merely fortuitous” (Irony xxiv). Though this is a simple statement and seems to explain niebuhrien irony plainly, Niebuhr’s definition holds various subtleties that need to be explained.

The ironic situation for Niebuhr was one in which events or circumstances at first seem random, but upon further analysis, it is later revealed that the two events were related. This is not to be confused with chance or luck. Irony, for Niebuhr, was above all a lack of understanding and self-awareness. This could be interpreted as being tragic or pessimistic if it were not for the very close religious associations Niebuhr placed with irony. The pivotal feature of irony is humor, and though man is incapable of recognizing the connected events due to his finiteness, God, being simultaneously removed from and apart of humanity, is able to do so, evoking “a wry sense of chagrin at the way the human condition works itself out in history, that the tendency of humanity to overreach is both predictable and comedic” (Holder 39). Thus, history, and the human condition is ironic and ultimately positive for though man sins by continuing to overreach and rebel against Nature and God, God expects this, and looks down with a knowing smile, ultimately in love and humor, not necessarily judgment.

Niebuhr felt America was the best example of irony. Prior to the twentieth century, and similar to today, America was able to conduct its business in its hemisphere without worrying about interference from other powers. America was her own master. This all changed though in the middle of the twentieth century when America became a global superpower; and though it was, and arguably still is, a great power in the world, by being placed into the center of the world stage, the United States is less in control of its destiny than before (Holder 39). America’s rise to power in the mid-20th century was not mere happenstance. It was a combination of fortuitous events (large material wealth and resources) and policy decisions (entering World War II) that put America into the limelight of the world stage. America’s irony stems from this moment: it was no longer a regional power with no responsibility to the world; it was now a world power leading others, a difficult task, and one in which Niebuhr felt the US was not ready.

Though all nations and peoples sinned, Niebuhr felt that world powers, especially imperial powers, including the United States, more easily committed the sin of pride, and thus irony was present due to their attempt to control the course of history. Great powers, including the US, feel that through economical, political, or military policy, world and historical events can be changed and more importantly controlled. However, what is never taken into account, are the often disastrous consequences of these policies. When these policies fail, and fail miserably, nations will then try to go into overdrive to “ever more frantically assert control, and to seek ever more extraordinary methods by which to control historical processes” (Holder 39). Niebuhr felt that the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century were nothing but the consequences of this vain attempt at control. Thus for Niebuhr, in order for America to escape this ironic situation, it must acknowledge this irony and the underlying paradoxes of American thought; however, by doing so would be to affront the very values and ideals that Americans are comforted by and firmly believe in. Of course this acknowledgement is never easy, and is rarely done by many Americans, especially its politicians, after all, who would elect a president who would openly criticize his or her own country? One president who openly praised and boasted America’s place in the world and specifically its exceptionalism was George W. Bush allowing me to present the next portion of this article, that of Bush’s analysis or understanding of American history.

Bush’s view was by no means unique; nevertheless his analysis fell into the critique outlined by Niebuhr’s work These critiques targeting the problematic belief in American Exceptionalism, the belief in controlling historic forces, the false promise of simple solutions and a lack of understanding in regards to the limits and constraints of power. (Bacevich Introduction) Throughout his eight years in office and the two military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, Bush’s foreign policy decisions and understanding of the world were completely out of sync with a Christian realist analysis of the world. Unable to see past the glory of the “[…] largest, freest, and most prosperous nation in the world […]” Bush’s analysis brought about what is known as the Bush Doctrine (Charge 286). This doctrine in which there is no distinction between terrorists and the nations that harbor them, which starts preemptive strikes in perceived enemies before they can attack the US or before these enemies can fully materialize, and which promotes and advances liberty goes against the major points and criteria for what Niebuhr would have considered “good foreign policy” (Decision Points 396-397).

This foreign policy admittedly and understandably was greatly shaped by the September 11th, 2001 attacks. However Bush’s personal religious beliefs also influenced this doctrine which from an exterior point of view demonstrates a striking contrast between Bush and Niebuhr. Both men were deeply religious and found personal comfort in Christianity. Niebuhr himself was one of the most referenced theologians of the first half of the 20th century and was a protestant minister as well as political philosopher. Though he never proselytized in his political discourses, Niebuhr’s “Christian realist” perspective of man and history made it difficult, even impossible to separate his political beliefs from his religious ones. Bush, on the other hand, has publicly acknowledged the importance of his faith in his personal and more importantly, his professional life, stating in his memoir before becoming president that his political ambitions were very much the influence of Divine Providence (Charge 19) as well as naming Jesus Christ as his favorite political philosopher during the 1999 primary debates (Decision Points 71).

As previously stated, the Bush Doctrine’s initial foundation was the September 11th, 2001 attacks. In his memoirs, Decision Points, Bush reveals his personal feelings on the morning of the attack, stating “my first reaction was outrage. Someone had dared attack the USA” (Decision Points 127). This response is telling from a Niebuhrien perspective due to Bush’s outrage at the audacity of someone attacking the USA and implies that the United States is somehow out of reach of what otherwise “traditional” states would be subjected to. This reaction was, and is quite common for most Americans today, and it reveals what Niebuhr called the “messianic” or “innocent” dreams of the nation (Irony 71). This attitude of perceived innocence and American Exceptionalism with the US being “the greatest nation in the world” stems from America’s puritan heritage where the founders wanted to establish a new Israel. This was meant to be a promised land for the chosen people to lead as a shining example breaking away from the shackles of sin, strife, and corruption of the old continent. However, as Niebuhr states, “[s]uch Messianic dreams, though fortunately not corrupted by the lust of power, are of course not free of moral pride which creates a hazard to their realization” (Irony 71). Thus, any attack against the United States is not just an attack against a sovereign state, but against God’s chosen people as well.

With over two hundred years of reaffirmed belief in America’s unique standing in the world, it is not surprising that the Bush doctrine wished to expressly and specifically punish those who would dare attack God’s chosen people. Whereas in the past, terrorist cells were specifically targeted for the actions of a few, under the Bush doctrine, the actions of a few became the responsibility of all. Where previously attacking specific terrorist cells or organizations was the norm, it is now common to launch a “War on Terror,” holding governments equally as responsible for terrorist actions as the cells and organizations themselves. This attitude and approach is just a continuation of American Exceptionalism. However, it must be understood that Niebuhr in no way refuted America’s unique, here to mean simply unique and not necessarily better, past. To do so would mean that America’s past and current situation were tragic or pathetic depending on the point of view. For Niebuhr, America’s Messianic past and idealism were ironic because they were partially merited. The Forefathers were able to keep tyranny and an extreme abuse of power at bay, not because of America’s inherent or intrinsic “goodness” as would past and present politicians would lead us to believe, but because of a variety of factors ranging from lack of a feudalistic or classic social structure to vast and abundant natural resources and land. The danger for Niebuhr, which Bush did not avoid, is when this exceptionalism and Messianic attitude is taken literally and out of context. Thus, specific threats i.e.: terrorist cells/organizations, become a larger, seemingly unending conflict against terror in general, all because of an attitude where America is the light and beacon of the world, destined to lead.

Naturally, this light must shine and for Bush, it did via the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Before launching these two wars, Bush affirmed the heavy heart with which he decided to send American troops. Nevertheless, he compares himself to Abraham Lincoln when, while looking at a painting of the 16th president, he states “After the attack, [the painting] took on a deeper meaning. The painting reminded me of Lincoln’s clarity of purpose: He waged war for a necessary and noble cause” (Decision Points 183). By putting in this passage, it is clear that Bush thought himself in a situation similar to Lincoln’s where this particular conflict was equally as just as the civil war. This, along with Bush’s constant defense of the need to remove Saddam Hussein from power reveals another Niebuhrian critique: man’s desire to control historic forces. Upon talking about the perplexities of modern culture, America’s economic and military strength in relation to other western powers, Niebuhr stated that, “[t]he perplexity arises from the fact that men have been pre-occupied with man’s capacity to master historical forces and have forgotten that the same man, including the collective man embodied in power nations, is also a creature of these historical forces” (Irony 140). Or to put it another way, man, and specifically leaders, are so enamored with the idea of controlling historic forces, that they forget that they are as much a product of these forces as in control of them. By Bush trying to ensure the security of the world through Saddam Hussein’s removal from power, he failed to take into account other factors that would affect the chances of success or failure in such a campaign. This brings me to my next and final points: Bush’s misinterpretation of the limits of power and the allure of simple solutions.

In his 2001 address to congress, Bush stated that “Americans should not expect one battle, but a lengthy campaign, unlike any other we have ever seen […] Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists” (Decision Points 192). This statement sums up the two Niebuhrien critiques left to discuss. Though Bush was absolutely correct in assessing the difficulties in waging such a war, he still didn’t understand the consequences of what pure military power would bring about. For Niebuhr:

Men and nations must use their power with the purpose of making it an instrument of justice and a servant of interests broader than their own. Yet they must be ready to use it though they become aware that the power of a particular nation or individual, even when under strong religious and social sanctions, is never so used that there is a perfect coincidence between the value which justifies it and the interests of the wielder of it. (Irony 40)

Though Bush’s use of power was “correctly” used as it was used for national and international interests, the potential consequences of it were not taken into consideration. The largest consequence being the overuse of power which in turn instigates issues and creates more problems. These unforeseen consequences are closely linked with the final Niebuhrien critique, that being of over simplified analysis and solutions.

In the Bush doctrine, guilt is equated with terrorist actions to not only the specific cell or organization, but to the country harboring them as well. This demonstrates an oversimplification in understanding “non-technological societies” as Niebuhr would have described. Such an analysis fails to take into consideration the local culture, history, or political organization of these countries and places blame on all. In certain countries or areas, it is very unlikely that groups or politically active people will act against leaders with ties to terrorist cells for fear of political or physical retribution. Similarly, changing the targets from specific cell organizations to a global “war on terror” over simplifies the enemy without taking into account the various differences between different types of terrorism. Even more so, it implies a war with no theoretical end. The paradox is that by having a war on terror, terror can never be ultimately eradicated because by always looking for potential threats, fear or terror can never be fully erased.

This oversimplification of the problem led of course to an oversimplification of solutions. The final part of the Bush Doctrine was to spread liberty and hope, via a western democratic model, with the ultimate goal of protecting America’s national security; the logic being: the more democratic or “liberated” nations that exist in the world, the less enemies America would have. Unfortunately, such a goal ignores the cultural specificities of non-western nations. What Bush failed to take into consideration, which Niebuhr had summed up perfectly even though he had been referring to the Cold War struggle was that:

Many of the values of [a] democratic society which are most highly prized in the West are, therefore, neither understood nor desired outside of the orbit of western society […] But even if they did understand [western values], they cannot be expected to feel the loss of liberty with the same sense of grievous deprivation as in the West. (Irony. 126)

In other words, western institutions and values cannot be expected to be transposed or transferred to a non-western context without expecting to meet some form of resistance. To do so ignores cultural and historical aspects of said culture resulting in unforeseen consequences, such as the sharp rise in sectarian violence in 2006 in Iraq and the historic difficulty of any power to maintain a presence in Afghanistan.

Of course, the explanation for the use of the Bush doctrine isn’t universally agreed upon. Though Bush proclaimed justification for primarily religious and humanitarian reasons, not everyone agreed with these justifications. There are of course a plethora of reasons for Iraq war depending on who is asked. Ranging in reasons from perceived failures and incomplete achievements of the 1990’s Gulf War to bi-partisan support following the September 11th attacks (6) there is an array of reasons given for the war in Iraq (Hanson). What is interesting to note however, is that regardless of the political leanings of the critics, pundits, or political scientists, oil was and is considered, by many, to be the primary factor for the invasion in Iraq regardless of Bush’s alleged religious or humanitarian reasons.

The CNN columnist, Antonia Juhasz, was very critical of the Iraq war, stating that the primary reason was for economic interests, mainly due to large oil reserves. She states “[b]efore the 2003 invasion, Iraq’s domestic oil industry was fully nationalized and closed to Western oil companies. A decade of war later, it is largely privatized and utterly dominated by foreign firms” (“Why”). Juhasz continues on throughout the article by stating that the humanitarian and religious reasons professed by Bush were nothing more than a façade. The real reasons for the invasion were economic in nature, and for the profit, not of the abused citizens of Iraq, but for American and other western oil companies.

On the other end of the ideological spectrum, Victor Hanson, Professor emeritus at the University of California and contributor to the National Review claims that oil was indeed a major contributor to the Iraq invasion, however, his reasoning and analyses were nowhere near as critical as Juhasz. For Hanson, American interest in Iraqi oil was not for America’s economic prosperity, rather it was an issue of global security. He argues, “[i]nstead, oil was an issue because Iraq’s oil revenues meant that Saddam would always have the resources to foment trouble in the region, would always be difficult to remove through internal opposition, and would always use petrodollar influence to undermine U.N. resolutions, seek to spike world oil prices, or distort Western solidarity…” (“Why did we Invade Iraq?”) Thus, for Hanson, Iraq was too dangerous to be in charge of its own oil reserve, and global security demanded American intervention.

The justifications and rationales for the Iraq war are numerous and can be defended on all sides of the ideological spectrum. However, regardless of the “real” reasons for the Iraq invasion, Bush’s personal religious convictions in deciding to intervene cannot be ignored. When Bush was told that he was a “servant of God” and how he was needed “for such a time like this [after 9/11],” Bush did not argue stating “I accept the responsibility” (Preston 603). Though the role of religion in American politics is nothing new, it seems that no other president was as open about his faith, and the importance of this faith in personal and political decisions. As Preston states in his analysis of religion on American politics,

Bush himself spoke of his own faith in similar terms – openly and unabashedly – perhaps more than any president before him. Just as he relied on religion to shape America’s response to the 9/11 attacks, he used it to frame other aspects of policy, both foreign and domestic. (Preston 609)

Regardless of the ideological lens through which one wishes to analyze Bush’s foreign or domestic policy, the importance of Bush’s personal faith cannot be denied. To do so would mean refuting the real-world consequences of Bush’s foreign policy, leading to my conclusion.

We are living with the consequences of that faith and that ideological lens even though Bush has been out of office since January 2009. American troops are still deployed and active in both Iraq and Afghanistan with no real pull-out date in sight. With Niebuhr becoming fashionable again thanks to President Barack Obama, hopefully the weaknesses and fallacies of the Bush doctrine will be corrected or improved. Accomplishing such a goal would involve resolving the irony of the Bush doctrine, and to an extent the irony of the American situation. Ending this irony would mean acknoweldging that Americans are to a certain degree, masters of their destiny. It would also mean however, that by being head of the international order, implies certain restraints and responsibilities, limiting the very destiny they wish to control. To truly break free from this constraint, and thus from the irony of the American situation, Americans would have to give up the very thing that has been paramount to their national and historical identity: being exceptional.

Bibliography

Bacevich, Andrew. 2008 “Introduction.” Introduction. The Irony of American History. (Chicago: Chicago University Press) Kindle File.

Brooks, David. Apr. 2007 “Obama, Gospel, and Verse” (New YorK: The New York Times) Web.13 Aug. 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/26/opinion/26brooks.html?_r=0

Bush, George. 2000 A Charge to Keep. Trans. Michèle Garène, Sylvie Lafon. (Paris: Odile Jacob) Print.

Bush, George. 2010 Decision Points. (New York : Crown) Print.

Fox, Richard. 1996 Reinhold Niebuhr: A Biography. (New York: Cornell University Press) Print.

“Global Public Opinion in the Bush Years (2001-2008)” Dec. 2008 (Pew Research and Global Attitude Project, Pew Research) Web. 15 Jun 2014. http://www.pewglobal.org/2008/12/18/global-public-opinion-in-the-bush-years-2001-2008/

Hanson, Victor Davis. 26. Mar 2013 “Why Did We Invade Iraq?” (The National Review) Web. 19 Jul. 2014. http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/343870/why-did-we-invade-iraq-victor-davis-hanson

Holder, Ward. Josephson, Peter. 2012 The Irony of Barack Obama (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Co.) Kindle File.

Juhasz, Antonia. 15 Apr. 2013 “Why the war in Iraq was fought for Big Oil.” (CNN.com,

Turner Broadcasting System, Inc.) Web. 19 Jul. 2014. http://edition.cnn.com/2013/03/19/opinion/iraq-war-oil-juhasz/

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 1926 “Henry Ford and Industrial Autocracy.” The Christian Century

43 (November 4, 1926):1355. Cited in Holder. Josephson. The Irony of Barack Obama. (Burlington; Ashgate Publishing Co.) Kindle File.

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 1952 The Irony of American History (Chicago: Chicago University Press.) Kindle File.

Preston, Andrew. 2012 Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith (New York: First Anchor Books) Print.

Schwartz, John. Nov 2010 “US to Drop Color-Coded Terror Alerts.” (New York: New York Times) Web.15 Jun 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/25/us/25colors.html

“Terrorist Attacks in the U.S. or Against Americans” 2014 (Infoplease.com, Pearson Education Inc.) Web. 15 Jul 2014. http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0001454.html

“Traveler Information.” (Transportation Security Administration) http://www.tsa.gov/traveler-information

Notes

(1) Terrorism was by no means a new enemy. America had known various domestic terrorist attacks in its history, including, but not limited to the Oklahoma City Bombings in the mid-nineties. What made this attack “different’ for most Americans, was its death toll, the fact that it was a foreign enemy no average citizen had heard of/known about, and the methods used to enact it.

(2) The Department of Homeland Security used to analyze terror threats based on various color codes. Red meaning that the US was on full alert with an imminent terrorist attack. This color code has since been revised for various reasons, including its vague definition of threats and criticisms of using the fear from potential enemy threats for political means.

(3) The peak of Bush’s domestic popularity was immediately after September 11th, where he held a 90% approval rating. This rating declined significantly throughout his two terms. (“Presidential Approval Ratings – George Bush” Gallup Gallup, Inc. 2014 Web. 15 Jun 2014) Internationally, Bush never benefited from such high numbers, even after the September 11th tragedies. Similarly, his approval ratings, be they negative or positive, were greatly influenced by the culture and country questioned.

(4) The critiques summarized here are largely due to Holder and Josephson who brilliant summarized Niebuhr’s original article. For a more detailed analysis, see The Irony of Barack Obama.

(5) Though sin has a deeply religious meaning, its importance to Niebuhr, and the consequences of sin that played out in human nature, and consequently, foreign policy, cannot be stressed enough. Niebuhr felt that part of modernity’s lack of understanding of history and world events was due to its refusal to admit that man, throughout time, has sinned, sins, and will sin.

(6) Victor Davis Hanson gives six reasons for why the US invaded Iraq in a perspective piece analyzing the consequences of the Iraq War 10 years later. The article primarily defends the Bush administration’s approach to the war by stating that the US, specifically the media and general population “derives from the general amnesia over why [the US] invaded.”

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

James, thank you so much for this rich essay. We have a few posts at the blog that continue to get a great deal of traffic, years after they originally went up, because they offer a primer or summary of an important issue/topic. I think your guided tour through the thought of Niebuhr on irony and sin will be a favorite destination for readers for a long time.

I am mulling over the possibilities of viewing de facto American exceptionalism (America as head of the world order, America’s fate on 9/11 as “consequently” leading the world into new territory) as an exceptionalism of accidents, not essence — I mean the possibilities for America, or Americans, and the rest of the world that is at present living with the accidental prominence of this country.

Maybe even “accidental” American exceptionalism doesn’t fit particularly well within the Niebuhrian vision — or, to go barreling back past Augustine and straight to Paul — of the problem of sin: its universality (“for all have sinned, and fall short of the glory,” etc, etc). But of course one of the consequences of Christological debates in the Western church was the affirmation that sin is not essential to human nature, but rather an “accident” whose effects human nature, unaided, cannot escape.

So, then, whence cometh our help? (This is more an observation than a question, but if the author or anyone else wishes to hazard a speculative answer, along Niebuhrean lines or your own, that would be delightful and interesting.)

A lot to mull over here, and I haven’t quite finished the piece.

Re American exceptionalism and “America’s puritan heritage where the founders wanted to establish a new Israel. This was meant to be a promised land for the chosen people to lead as a shining example breaking away from the shackles of sin, strife, and corruption of the old continent….”

That has indeed been a persistent theme or undertone in U.S. history; however, Americans are, arguably, not the only ones to have seen themselves, at one time or another, as a chosen people. The medievalist Joseph Strayer contended that there was “a cult of the kingdom” in late-medieval France (c.1300) that included the view that “like the Israelites of old the French were a chosen people, deserving and enjoying divine favor.” (Strayer, On the Medieval Origins of the Modern State, 1970, p.56). Fast forward several centuries to the French Revolution and one sees, in some quarters, the notion of France as beacon of republicanism and enlightenment with, in the views of some political groups (notably the Brissotins), a responsibility to spread, if necessary by force, its revolutionary ideals to the rest of Europe and/or the world.

Admittedly this has nothing to do with Niebuhr, but especially since the author of this essay is French, or at least is based in France, I thought, in the what-the-heck spirit of blog commenting, that I might as well toss it out, for whatever it might be worth.

Perhaps, later on, I will have something to say that is more directly related to the main topic of the essay (or perhaps not…).

Hello all,

I am the author of this work and I am pleasantly surprised by the responses that I’ve received thus far! I am indeed based in France, but not French (not yet anyway). I’m glad my essay has sparked some conversation and interest.

For convenience’s sake, I will respond in order of comment publication. So to respond to Lora, and I apologize for the brevity of this response but I would say a Niebuhrian response on “whence cometh our help” would simply be: ourselves.

The paradox of human nature is of course that we are a contradiction. We are both apart of, and independent from, Nature. Similarly, we are capable of great creation and destruction. Regardless of American exceptionalism being “accidental” or “ironic” is that, if I had to postulate, and I must confess that my Niebuhrian analyses are often lined with Pragmatism, the origins of American exception are of little importance. Regardless of the origins, we have to live with the consequences of these beliefs. For Niebuhr, avoiding the pitfalls of American exceptionalism would require above all: critical self-reflection and SINCERE contrition before God and His divine Grace.

This was the hard part for many according to Niebuhr, as Sin (i.e. pride) often prevented human beings from seeing the true reasons behind a person’s actions. Otherwise put, even when we do something good, it’s not always as selfless as we often believe or claim.

From a theological point of view, Niebuhr’s understanding of God would not provide the “help” either, as he was critical of God as person belief. God was beyond humanity, even though He was paradoxically apart of it. Of course, it musts be understood that Niebuhr’s theology was never developed as far as other theologians. He preferred to leave such questions to the “real” theologians such as his brother. For Niebuhr, his focus was on the real applications of Christianity in the modern world.

Though Niebuhr’s theology seems to reject any form of outside help on avoiding the pitfalls of American Exceptionalism, a.k.a. pride, one should not fall into despair. Niebuhr was not a cynic and firmly believed in the Grace of God. However, this Grace, ironically would have to be realized through the freedom bestowed upon humanity by God to look inwards and to understand oneself and to be critical of one’s motives in order to achieve true contrition and humility.

I hope, Laura, that this “answers” your question. The short and the long of it is as follows: God’s gift of freedom upon humanity is ultimately our source of both damnation and salvation. Because we are free, we often try to go beyond our means (i.e. become like God) which is the Sin of Pride. Nevertheless, it is in this very freedom where we can find the source of our redemption as we can use it to look inwards uninhibited by society or nature, understand ourselves ultimately to find humility and thus Grace.

As for Louis’s comments:

Your comments are valid, and deep-down some, if not most, French citizens still think that the French civilization is the best of the world. But this type of attitude is exactly what Niebuhr was discussing in The Irony of American History. For Niebuhr, all powerful nations at one point or another, believed in some concept or notion of “exceptionalism” often at the summit of that nation’s power and influence. The “irony” for Niebuhr in terms of America’s understanding of its own place, is its refusal to acknowledge anything other than “moral,” “just,” or “non-political” reasons in any of its actions. European powers have acknowledged, granted a few centuries later, that previous incarnations of these nations were imperial and thus, by definition had ulterior motives than being simple beacons of hope, freedom, knowledge, culture etc. Granted, this point of view comes from a 21st-century perspective where it is easy to pass normative judgements on previous empires and cultures. Where European powers may still try to hide current foreign or domestic policy actions behind a thin veil of “reasonable” justifications (political, economic, or social), they very rarely evoke the heavy-handed, normative, and moral justifications used by the American government (perhaps Dominique de Villepin’s speech at the UN against the American invasion of Iraq is an exception).

For Niebuhr, this is what made, and to a certain extent, continues to make, the US ironic: the US still persists naively, that it is still an innocent nation always on the side of “Good”. European and other powers at least acknowledge that some degree of self-interest is behind their decisions. In order to escape this irony, Niebuhr argued simply that Americans needed to take a better look at its history, and more importantly, a critical analysis of its national identity.

I do apologize for the long responses and hope they have been able to shine some light on Niebuhr and applying him to a 21st-century perspective. I am by no means an “expert” on Niebuhr, as a matter of fact I study John Dewey almost as much as Niebuhr, but I do find his thought fascinating.

Thank you again for your interest! And of course, if you have further questions or comments, I look forward to reading them!