Nearly three months after seeing his church burn, Samuel Willard returned to the pulpit. By spring 1676, King Philip’s War had ravaged a dozen New England frontier towns and tradeposts like Willard’s Groton. Willard, a 36-year-old Puritan clergyman, discovered that his well-fortified home was one of the few to withstand repeated attacks. The church, however, was lost.

So, with wife Abigail, Willard joined roughly 300 of their neighbors, also in flight from the raiders. Hastily resettled in Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood, Willard seized the chance to preach the artillery election sermon on Monday, 5 June 1676. Since the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company’s 1638 charter, the annual event doubled as a roll call of colonial power brokers, with the royal governor, newly minted officers, and local gentry all lining the pews. The militia swept through the city, paused for prayer and Willard’s sermon, then capped the festivities with a feast at Faneuil Hall. Still mourning Groton’s loss, what could the refugee clergyman say to the soldiers? What were the words that Samuel Willard carried from and to war?

Local trauma stained Willard’s new text, and gave his sermon metaphors extra force. “The heart of man is a little Kingdom, or Dynasty which owes Fealty to the Crown and Empire of Heaven, understanding, will, Affection, and all their Operations are to be employed in Gods Service,” Willard preached. “The keeping of the heart here required implies, and intends both danger and duty.” In his sermon, published as The Heart Garrisoned, Willard sketched the ideal Christian fighter for his audience to emulate. “Get the Heart and Spirit of a Souldier,” he instructed, directing the militia to develop qualities of prudence, fortitude, hardiness, fear, sobriety, and fidelity. Crafting his acknowledgments for the “train-bands’” service, Willard ended the lesson on a typically providentialist note. “Remember, if you are Christians, you are bound for Heaven, your way lies through the Enemies Country, and you have a great Charge to carry with you… a Soul given up to God, & devoted to his Service,” Willard wrote. “Heaven is a prize reserved for him that keeps his heart.” Two years later, Samuel Willard stepped in to lead Boston’s Third Church (and then Harvard), while many of his former parishioners left to rebuild Groton.

The artillery election sermon stayed on the city books, held every first Monday in June for the next few centuries. Boston militia members heard radical variations on the themes of Christian patriotism and republican duty. Sometimes, preachers froze in the face of a regular cultural prompt. (Intellectual history goldmine, researching a reinvented religious tradition still in colonial process!) Roughly 15 minutes into his 1674 sermon, for example, Joshua Moodey sputtered that his discourse would be “a Divinity-Lecture to such, i.e. Military-Divinity, or Divinity Souldiery.” In the end, Moodey went with a fairly modernish term for the day: “souldiery spiritualized.”

The artillery election sermon stayed on the city books, held every first Monday in June for the next few centuries. Boston militia members heard radical variations on the themes of Christian patriotism and republican duty. Sometimes, preachers froze in the face of a regular cultural prompt. (Intellectual history goldmine, researching a reinvented religious tradition still in colonial process!) Roughly 15 minutes into his 1674 sermon, for example, Joshua Moodey sputtered that his discourse would be “a Divinity-Lecture to such, i.e. Military-Divinity, or Divinity Souldiery.” In the end, Moodey went with a fairly modernish term for the day: “souldiery spiritualized.”

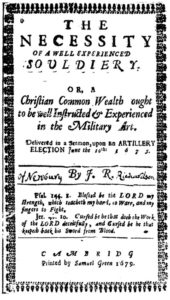

Other clergymen relished the chance to issue reforms. Urian Oakes, briefly a Harvard president, took a swipe at the militia members who enjoyed rowdy “training-days” and “excessive drinking” in 1677. “Please God, if you would engage Him on your Side, to govern Time and Chance to your advantage,” Oakes chided. As the 1670s gave way, J.R. Richardson adopted a sterner approach. “A Christian people ought to be Conscientiously Trained up and experienced in Military skill

,” he preached to the election-day crowd. “There is a Civil as well as Spiritual Warfare that a Christian must be exercised in.” The militia, to Richardson and others, underscored the natural duty of a Christian commonwealth and of an obedient colonist.

These were some of the ideas that Samuel Willard and his peers carried from and to war. As a forgotten rite and understudied corner of America’s history of religion—much like fast days and thanksgiving sermons—artillery election orations deserve sharper scrutiny. This summer, when I’m not at work researching early American women thinkers

(stay tuned for a biographical panorama!) I’m wading through this reading material: the annual artillery sermons of 1638-1916, heard by the Boston militia and recorded in various Proceedings and company histories. You’ve read a quick sample of the kinds of 17th-century texts that I’m dealing with here. Taken together, I’m curious to see 1) how early American religion shaped cultural ideas of the “Christian soldier” and “Church militant”; 2) how Civil War and global conflict changed religious messages to/from the militia over time; 3) whether looking at organized faith operating in this kind of space (annual, interdenominational, urban) alters what we (think we) know of national religious formation; and finally 4) whether doing a “small-batch” early American intellectual history project like this one (with a very local, print-culture focus) can recover some lost rites of modern thought.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

R. Todd Romero provides a brief synthesis of scholarship on New England artillery sermons halfway into his Making War and Minting Christians , but I still yearn for more. For instance, did postwar sermons and veteran audiences reconfigure gubernatorial politics? What about Boston orations during eighteenth-century imperial wars? A compelling post.

Thanks, Cory, I will take a look at Romero’s work. Scholars have used c18 sermons to demonstrate revolutionary “spirit” in action, and the c19 sermons are equally fascinating, especially those given in the wake of the Civil War. Also, I like your idea of tracing the arc of gubernatorial politics, given that the Mass. Constitution of 1780 debates included talk of whether/not the governor could appoint militia officers. To round out that executive layer of the story, it’s worth delving into the political affiliations (if traceable) of the artillery officers. More research required!