The story of William Henry Harrison’s run for president in 1840 holds a special place in the history of American presidential elections. Not only did Harrison die after a month in office, his ‘log cabin and hard cider’ campaign, run by the Whig party, still stands out as a uniquely rambunctious episode. Preferring a former general and Indian fighter for a second consecutive time over the more celebrated personas the party boasted, such as Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, the Whig party was determined to battle the Jacksonians on their own terms. They not only chose to run with a former military man, they set out to match the Democrats in cultivating a broad populist appeal. And indeed, the Whig machine under the direction of the illustrious Thurlow Weed unleashed an energetic campaign unrivaled in the scope of its mobilization until then in the history of presidential elections. Not surprisingly the 1840 elections witnessed the highest turnout until then in the history of presidential elections: more than 80%.

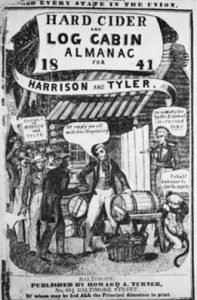

To the great delight of the Whig campaigners—a story they relished telling time and again—it was conversely a Jacksonian Democrat who provided them with their most famous piece of propaganda material for their 1840 presidential campaign. Casting Harrison as an old man best fit for retirement, a reporter for the Jacksonian Baltimore Republican exclaimed “Give him a barrel of hard cider and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him and my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in a log cabin by the side of a ‘sea coal’ fire.” Whig campaigners pounced on this jest, turning it on its head. Whigs used the ‘log cabin and hard cider’ symbolism, as they contrasted the image of their purported rough-and-tumble frontier candidate, Harrison, with the supposedly aristocratically inclined Democratic candidate and current president, Marin Van Buren. While Harrison spent his days drinking hard cider in a crude log cabin, so the story went, Van Buren lived lavishly in his Washington palace, wasting public funds on such luxury items as Champaign.

While scholars had traditionally looked to the language and theatrics of the ‘log cabin’ campaign as emblematic of the changes in American society and culture by 1840, more recently historians have tended to underplay the significance of the campaign. For earlier scholars it marked a watershed moment in the history of the United States as a fully fledged democracy, while recent scholarship has tended to interpret it as a gimmicky sideshow. This seems part of a general inclination to view the Whig/Democratic political divide as more significant then past historians had. While ‘consensus’ and ‘symbol and myth’ scholars in the 50s and 60 construed American political history as offering contemporaries a very limited array of ideas (1), today historians prefer to cast political struggles of the past, and especially the Whig and Democratic parties, also known as the second party system, as offering voters very different political avenues to choose from. Furthermore, it seems that recent histories tend to pick their horses in such narratives, sympathizing with one side or the other much more than they had in earlier times—with the exception of Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s The Age of Jackson (1945). While Sean Wilentz’s The Rise of American Democracy (2005) seems to side with the Democrats, the competing synthesis of the period, Daniel Walker Howe’s What Hath God Wrought (2007) seems much more partial to Whig politics. Both of course do not pay much attention to the log cabin campaign. While Wilentz seems to view it narrowly as a useful campaign strategy and a facade for a Whig Party that would do anything to win, Howe suggests that we look beyond the antics and listen to the well-articulated agenda Whigs promoted over that very campaign. Indeed, both want us to regard the party system of the period as indispensable for understanding the course of American history.

After reading the recent roundtable about Andrew Hartman’s book on the Culture Wars, A War for the Soul of America, it occurred to me that writing history during the heyday of the Culture Wars might explain this historiographic trend. This might sound a bit ironic, for one would think that historians would take cultural effusions in history seriously during heightened periods of culture clashes, such as the Culture Wars. However, one of the effects of such culture struggles is a creation of a seemingly well-understood arena of conflict in which either side easily recognizes friend and foe. In this vein, during the Culture Wars the political party system tended to align with the cultural divide and became an extension of it, and vice versa. Thus, conventional politics might seem during intense periods of culture conflicts as more significant than they appear at other times, when alignments are not so transparent. Thus it would make sense that observing history in the 50s and 60s, historians would allow themselves more leeway to interpret the political rifts of past centuries as less consequential than they appeared to contemporaries. Indeed, even at times as ‘much ado about nothing’. By contrast, more recent histories would tend to cast the high-pitched political struggles of the 1830s and 1840s as substantive debates in which each side held and promoted very different agendas with crucial implications for American history.

This of course holds true so long as historians view contemporary politics as consequential. Indeed, when the long-time Marxist Alexander Saxton released his political history of the period The Rise and Fall of the White Republic in 1990—also during the Culture Wars—he probably did not think that the Democratic and Republican parties of his time offered much in the way of alternatives. Not surprisingly, in his account of the Whig/Democratic conflicts he cast both as first and foremost advocating for white supremacy. Though he remained true to Marxist analysis by interpreting the Whigs and Democrats as to some degree corresponding to class conflict in the period, he highlighted the extent to which mainstream popular culture from the period underscored the agenda in common to both parties—western expansion and white supremacy. (2)

[1] Perhaps the best examples from each school are Louis Hartz, The Liberal Tradition in America (1955) for consensus history and John William Ward, Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age (1955) for symbol and myth.

[2] Historians influenced my Marxism tend to view the Jacksonians as representative of the working class and often have more sympathy for them, see the case of Charles Sellers The Market Revolution (1991). Saxton to a certain degree avoided that inclination by stressing race as a no less crucial category.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I wonder how David Greenberg covers*, or might cover, this topic in his new book, The Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency? If he didn’t cover this, it might make an interesting reverse-chronological sequel for him. – TL

*Looking at his book promo materials, it appears he only goes back to Theodore Roosevelt. And I don’t know how much he covers campaigns, if at all.

I always like to say that my favorite president is Harrison. Though personally he did plenty of damage, as president he didn’t have time to do much damage.