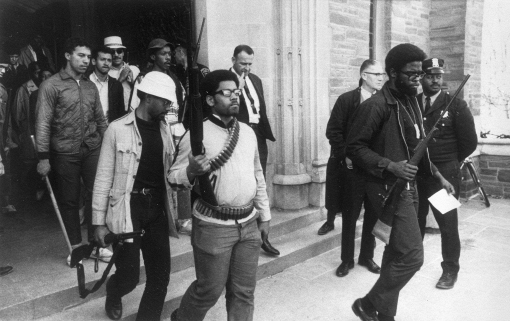

Cornell students leaving Willard Straight Hall at the end of its occupation, April, 1969.

,” Nathan Heller’s account of student activism at Oberlin College in the current issue of The New Yorker, has been the source of much conversation online over the last few days. Though the piece shares some annoying tics of the evergreen “what’s gone wrong at our college campuses?” genre, Heller at least tries to be relatively even-handed in his reporting, talking at length with students, faculty, and the college president.

But I have been struck by – and annoyed at – the ways in which the discussion of Oberlin and the Heller piece – like earlier discussions about events at Yale and the University of Missouri – has fallen into very old patterns of talking about a very old kind of student behavior. So, at the risk of stepping into the professional turf of Andrew Hartman and L.D. Burnett, here are some of my thoughts on this.

Students’ revolting against college and university authority is a very old phenomenon in American academic life. Indeed, such behavior goes back at least to the beginnings of the modern American university.[1] For at least the last fifty years, one of the forms that such student behavior has taken is political organizing against the reigning vision of college education. Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement (1964-65) was, among other things, a critique of the “multiversity,” UC President Clark Kerr’s vision of modern higher education. At Cornell, in April 1969, members of the Afro-American Society occupied the student union, Willard Straight Hall, making a series of demands to improve the lot of African Americans students on campus and to increase the number of African American faculty. The occupation may be best remembered today for the Pulitzer Prize winning photograph of the students leaving Willard Straight Hall at the end of the occupation, brandishing guns.[2] Before, during, and after the occupation, the Cornell administration tried to accommodate at least some of the demands of the AAS. Out of the protests eventually grew a Black studies program. In the 1980s, the struggle over the Western Civilization requirement became a flashpoint at Stanford, leading to its own share of protests (this is the subject of an award-winning dissertation and forthcoming book by our own L.D. Burnett).

Events at Berkeley, Cornell, and Stanford divided both students and faculty, often bitterly. And each of these events became powerful political symbols beyond campus. Especially off campus, these events have tended to evoke a louder response from those upset by them than from those sympathetic to student protestors. And the response has tended to be similar in each case. The students are spoken of as privileged and ungrateful. Their behavior and demands are treated as threats to the very existence of liberal education and a threat to society at large. Back in 1966, Reagan made this sort of response to events at Berkeley one of the major themes of his successful California gubernatorial campaign.

Half a century into this long history, it’s a wonder that events like those at Oberlin continue to evoke apocalyptic fears. Over those five decades, American colleges and universities have faced – and continue to face –a variety of real threats. But such student protests have somehow never managed to destroy American higher education. Yet, we predictably continue to get pieces like Rod Dreher’s response

, at The American Conservative, to the Heller article on Oberlin, which see events on that campus as a brand new sort of outrage.

Dreher’s piece also has another common feature of hysterical responses to students behaving like, well, students: the presumptively new awfulness on campus reflects larger new and horrible things taking place in American culture as a whole. But I’ll let Dreher “explain”:

There’s a part of me that takes pleasure in the irrationality of the contemporary cultural left destroying itself. But these are actual lives here, and institutions that people now gone have loved, and took generations to build. All being dismembered by ideology and pathology. This doesn’t just happen, though, and Oberlin is not the only school like this. This sickness says something about the American ruling class. Only because he takes his cues from a culture like this could a President of the United States order every public school in the country to let boys who think they are girls use the locker room. The backlash in this country when it all starts to come apart is going to be a terrible thing to behold. If you’ve read your Dostoevsky, and if you know your early 20th century history, you know where this kind of thing went in Russia.

[Thanks, Obama!]

The long history of students attacking the institutions in which they find themselves should remind us that such demands are not signs of the end of the world – or even the end of liberal education. But it should also suggest that what is really most interesting about particular protests are likely to be local factors, in both place and time. Events at Oberlin this past year echo – in many ways – events at other, very different campuses, like the University of Missouri and Yale. But they are also distinct to Oberlin. There are probably new and interesting things going on, but we will only see them if we’re willing to stop being shocked and surprised at the mere fact of students behaving like students.

Being willing to look in detail at what’s happening on the ground at a particular institution at a particular time is, I think, necessary to draw actually well-founded conclusions about the broader implications of such events. Doing so also involves rejecting the strong tendency to, instead, simply put events like those at Oberlin in the service of some larger narrative, about free speech, “identity politics,” the supposedly feckless faculty, privileged and immature students, the decline of our colleges and universities, or even the politics of Israel / Palestine. Colleges, especially small liberal arts colleges, really are communities. And taking them seriously as such, rather than treating them as chits in one or another culture war, is a necessary first step in understanding and resolving tensions like those that appeared this year at Oberlin.

___________________________________________

[1] See Chapter 2 of Mark Carnes’s Minds on Fire (2014) for a nice, short history of what he calls “subversive play” as a perceived threat on American college campuses.

[2] According to Ian Wilhelm, in an excellent but unfortunately paywalled recent Chronicle of Higher Ed piece on the Cornell events, they had begun the occupation unarmed, but had acquired guns after white fraternity members had threatened to disrupt the occupation by force.

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Ben, thanks for this great post. No worries on turf — much like the Mad Hatter’s tea party, there is plenty of room for everybody here, though the table is a bit of a mess.

I’m working on a freelance piece now re: the history of the “kids these days” higher ed declension narrative, a staple of magazine feature writing for decades. So I won’t go into too much detail here, except to point out that the Heller piece was a particularly notable example of the ad hoc anthropological mode that this writing frequently takes, especially when it comes to discussing events at elite universities. That mode delivers certain pleasures to the reader — and a certain status to the writer. But it also exoticizes and sensationalizes its subjects and their “habitat” and their social rituals. Not that Oberlin wouldn’t be a somewhat exotic “habitat” for many readers — but maybe not that far beyond the pale for New Yorker subscribers. Indeed, what this piece shows in its best moments is what a strange environment an elite college can be for first-generation students or students from underprivileged backgrounds or underrepresented groups. But those insights are visible in some places only through an almost imperceptibly thin but still unmistakably visible tissue of disdain. Again, though, that’s one of the satisfactions this genre can offer to both readers and authors — the reassurance that wisdom rests with the observers, not with the observed. “Sophomores are shockingly sophomoric; film at 11.”

Oh yes, middle-class conservatives and the petit bourgeois railing against the savage decadence of those footloose and fancy-free college kids. But they are *above* it all because they are *outside* of it. Sigh. – TL

LD – The “kids these days” piece sounds amazing. Can’t wait to read it.

LD, I think you capture very well here the general aesthetics and politics of this often annoying subgenre. What I enjoyed from the Heller piece is how at the same time that it does offer instants of that moralistic sensationalism it opens itself up to subverting that logic and its inherent paternalism, particularly through the inclusion of students’ voices and the discussion of class and race and the limits of higher ed institutions in general.

From the first paragraph (which is all I’ve read of it) of the Nathan Heller article:

A year earlier, a black boy with a pellet gun named Tamir Rice was killed by a police officer thirty miles east of Oberlin’s campus, and the death seemed to instantiate what students had been hearing in the classroom and across the widening horizons of their lives.

You know what *really* marks the collapse of Western civilization and liberal education etc etc [insert ‘trademark’ logos]?

It’s not Oberlin students complaining about the sushi. It’s not a transgender student using a particular bathroom. No, it’s the fact that the word “instantiate” appears in the opening paragraph of an article in The New Yorker. The entire staff of the mid-20th-century New Yorker — minus those who may still be alive — must be twirling in its graves.

Really? Is this the place to bring one’s Macdonaldesque cultural airs?

Of course we’re being tongue-in-cheek here — at least I hope so.

Sorry. I’m not the best at reading tongue-and-cheek in two dimensions. I come here too often with my no-sense-of-humor hat on.

Well, actually, Tim…

I’m kidding.

A certain lightness of heart is hard to come by these days. It’s hard not to feel dread and despair about the state of the body politic today, or the state of the university, or the state of pretty much anything at all — and we’re all collectively showing the strain.

I am reminded of Dickens’s description of a catch crustaceans (don’t remember if it was lobsters or crabs) in David Copperfield: the critters were all piled on top of each other in the trap together, alike doomed, but — or, and — indiscriminately pinching anything within reach in a demonstration of general ire. That’s what the current moment feels like sometimes. And of course sometimes it’s important — or at least it seems important — to get right in the middle, clawing and scuttling with the best (and worst) of them…but strategically, if possible, though there is no telling what will hit a nerve and what won’t, or what effect it will have. (Judging from my own blog traffic/feedback since yesterday morning, I hit a few nerves!) Sometimes it’s a good thing just to be reminded that we all still have some fight left in us, even if we are stuck in the hegemonic lobster trap. Where there’s life, there’s hope. And humor too.

Thanks for a fascinating piece Ben. To cautiously generalize the apocalyptical hysteria seems to be infecting our political discourse as well. I really cant understand the the fear I’ve noticed in the last 6 months over this passionate electoral season. I would think which ever side of the electoral divide you are on, heatedly contested primary races would demonstrate the health of our democracy not the first signs of its downfall. For the first time in perhaps a generation larger structural issues are being raised in political campaigns, of course the rhetoric will be heated, but i don’t think we as a nation are flirting with armageddon just yet. I mean this far into the election and no large scale violence (and we had one presidential election already devolve into civil that country survived ) suggests that the Republic will survive 2016. To inject a little flippant humor I’ll become more worried at the first sign of congressional canings. best

I agree with the idea some students have always protested against the established order. IIRC correctly in my day (early 60’s) student activism was splintered: SANE was organizing (http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_national_committee_for_a_sane_nuclear_policy_sane and there were still protests against parietal rules http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1963/10/1/parietal-rules-pdean-monro-and-watson/).

The early 60’s were still in the period where the proportion of (white) high school graduates going to college was rapidly increasing, so there may have been more caution about rocking the boat. What’s different these days is the greater diversity of students and their activism.