As I’ve recently returned from a two-week journey to Israel, I wish I had some profoundish, comparative analysis to serve up this week; but alas, I think Eran long ago covered everything I would have to say on that score.

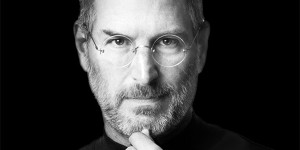

However, I did find some inspiration during my return. As transatlantic flights are good for nothing if not watching movies you would otherwise ignore, I managed to consume four different films between Tel Aviv and Toronto. One of them was the Aaron Sorkin-scripted film Steve Jobs.

Eran has told me that he recalls someone claiming that Nietzsche once said something to the effect that everyone in their life has basically one good idea, which they then spend the rest of their life developing and recycling.[1]

This certainly holds true in Aaron Sorkin’s case, whose one idea was, of course, talking while walking. And in that regard – in being both entertaining and irritatingly unrealistic at the same time – Steve Jobs is exactly what you would expect.

Yet there is another core idea in Steve Jobs that some – as we’ve been reminded in this week’s awesome roundtables on Andrew’s book – might regard as the one “great” (as in large rather than good) idea of the 1960s: individualism via consumerism. Jobs’ most significant contribution to American culture, after all, was cultivating the idea that one can purchase and posture their way to creative genius. This is particularly emphasized in the final act of the film, as we watch the various characters comment on the “Think Different” campaign of the iMac launch. To be fair, there is voice given to how ridiculous and ironic that campaign was; Jobs’ daughter, for instance, is particularly unimpressed. Nonetheless, in the final minutes of the film, Jobs’ redemption (which unfortunately you sense is always coming, despite the rest of the movie establishing his indisputable status as a complete jerk) unfolds to the backdrop, quite literately, of the evocation of the supposed giants of individualism, from Albert Einstein to Martin Luther King. Thus we are presented with the rankly offensive suggestion that anything Jobs was involved in partook in any way with the extreme righteousness and bravery of someone like King.

Yet not all of the figures recruited for the publicity campaign seem inappropriate. Bob Dylan, who is referred to explicitly several times during the film, seems a particularly apt choice. Watching all the characters in the movie struggling to align their orbit with Jobs’ motivations and/or mythical sense of decency reminded me of the frustrations experienced by Dylan acolytes so brilliantly explored by Kathryn Lofton at the 2014 S-USIH conference. Both Dylan and Jobs are widely regarded as geniuses that channeled the zeitgeist of the future Cool Kids of the country, providing new generations with ways to feel as though they existed outside the prison of American mediocrity while actually helping ensure that it flourished like never before. They also both seemed to go out of their way to be unlikable and perhaps even unlovable, refusing to unambiguously sign up for any cause that did not revolve around them doing whatever the fuck they wanted to do. But gee, Sorkin seems to suggest, isn’t that why we love them after all? Oh Steve, so stubborn and so obsessive! But I guess the brilliance that moves us all forward just cannot be purchased with any currency short of sociopathy.

And yet there are some differences between Dylan and Jobs. Dylan did not emphatically insist on the importance of what he was doing, or speak in terms remarkably adaptable to an Aaron Sorkin script about changing the world or “inventing the future.” On the contrary, what made Dylan so inscrutable was his unwillingness to embrace or acknowledge why other people thought what he did was so important. I am reminded of a moment in the excellent documentary on Dylan, No Direction Home, when Joan Baez recalled praising his lyrics while he shrugged and said he didn’t even know what they meant! Jobs, on the other hand, always knew what his products meant; or at the least, he knew they were super cool.

And yet they still have enough in common to speculate that both of them represent variations on a theme. (The most trivial of these perhaps being, humorously, that Jobs also dated Joan Baez.) Might I suggest that this could be the jumping off point for an ambitious project? I already have the title – Think Different: A History of Individualism and the American Asshole.

[1] Note that we have no idea whether this is true or not. Do you?

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I appreciate the amusing parallels, but there might be a difference in terms of audience and agency, though. Two things occur to me: for all his dominating influence, Dylan was still an option of individual taste. If you didn’t like his music, there wasn’t a whole industry working on forcing you to change your mind. If you loved his songs, it was because they did things to your heart/soul/psyche or whatever, beyond the pleasure of the audio experience. But Dylan left that with you, as your individual share in the deal. Jobs seems different, creating a kind of globe-spanning consumer/commercial universe that was/is difficult to get outside of, as the alternatives for computer, IT, phone, etc became whittled down rather than expanded. Dylan’s “The Times They Are a’ Changin'” sounds like a song from its era, but it’s not dead or even irrelevant. The candy-colored iMac is now just plastic and metal junk, however.

Robin: You’re making me SO glad that I haven’t seen Steve Jobs. Oh, and sociopathological deviancy doesn’t matter so long as profits result! – TL

And it occurs to me that Jobs’ life was just another Silicon Valley riff on Thomas Frank’s Conquest of Cool. – TL

I am with Tim: this post reiterates for me why I will never see watch this film. Regarding Dylan, there’s another very important difference: he did not play the game of authenticity and was quite the chameleon, almost a postmodern avant la lettrre. While Jobs is quite the opposite. Todd Haynes’s beeautiful fictionalization of Dylan in his movie I’m Not There does an excellent job in showing Dylan’s ever shifting ways (and it deserves to be seen just for how it reimagines the biopic form, subverting the typically tedious telelological narrative that presents us the historical character’s inner conflicts and mishaps to tconclude in a resolution of redemption.

@Tim & Kahlil: Indeed, not seeing the film is the course of action I would recommend! And you’re totally right Kahlil; I thought of also mentioning how Dylan actively rejected the mantle of authenticity thrust upon him all the time, infuriating his fans, which was the opposite of what Jobs did, insisting on his purity until the end.

@Martin: I also agree with you and, although I dislike both Jobs and Dylan, ultimately I have a lot more respect for Dylan – because by refusing to participate in his own deification, he did not so actively help to build the ideology of individualism via consumerism.

As cries of sell out, traitor, and, even, Judas, rained down on Bob Dylan and the Hawks on some of the great stages of the world, Allen Ginsberg, from the perspective of a poet, explained what ws happening: “Dylan has sold out to God. That is to say, his command was to spread his beauty as widely as possible. It was an artistic challenge to see if great art can be done on a jukebox.”

As for Dylan, he was more than equal to the task.