In his 2015 book, The Rise of the Right to Know, Michael Schudson argues that an important driver for that rise, in the post-World War II United States, was “a general shift to a more critical culture in…society” (p. 109). I think Schudson’s narrative is Panglossian, even within the chronology he covers, but let me attempt to provide his full argument before I offer a refutation.

In his 2015 book, The Rise of the Right to Know, Michael Schudson argues that an important driver for that rise, in the post-World War II United States, was “a general shift to a more critical culture in…society” (p. 109). I think Schudson’s narrative is Panglossian, even within the chronology he covers, but let me attempt to provide his full argument before I offer a refutation.

I.

Schudson bases his “critical culture” thesis on postwar developments in higher education. First, according to Schudson, there are the facts of increased affluence and growing college attendance. Second, with attendance and affluence came the fact that “a large majority of students majored in the liberal arts.” Third, “a restive faculty” in this era were encouraged to be creative and “increasingly rewarded [for] orginality.” Schudson assumes that faculty then either served as exemplars for hungry young knowledge seekers, or brought this creativity to the classroom. For the purposes of his overall argument, Schudson forwards that these three factors resulted in an undergraduate student population “encouraged to develop skills in critical thinking and [that] learned to read against the grain of assigned texts.” This “educational revolution” (using the phrase coined by Talcott Parsons in 1971) fostered, Schudson eventually argues, a market for more facts about society and government. These newly minted critical thinkers would also consume the products of investigative journalism that arose in the late 1960s and early 1970s. [1]

If the basis for this line of thinking sounds familiar to you, it may be, according to Schudson, because you are familiar with David P. Baker’s work, The Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global Culture (Stanford, 2014). Baker is a sociologist of education. I hadn’t heard of Baker’s book before Schudson’s citation.

In The Schooled Society Baker forwards an all-encompassing thesis about the power of education, but higher education in particular. Generally, he argues that “the ubiquitous massive growth and spread of education has transformed our world into a schooled society—a wholly new type of society where dimensions of education reach into, and change, nearly every facet of human life.” He adds that “formal education…has become such an extensive undertaking that society is influenced by its logic and ideas more than the other way around, and this has been so for some time.” This education, he continues “transforms individuals…but also produces a widespread culture of education having the legitimate power to construct new types of minds, knowledge, experts, politics, and religions.” The result is a “massive secular faith in education along with frustration at unmet, albeit unrealistic, grand expectations.” At the root of this change is the university, particularly “over the past fifty years by a supercharged form of the research university and mass higher education. The university, then, is “perhaps the single most dynamic creator of cultural understandings in postindustrial society.” [2]

In The Schooled Society Baker forwards an all-encompassing thesis about the power of education, but higher education in particular. Generally, he argues that “the ubiquitous massive growth and spread of education has transformed our world into a schooled society—a wholly new type of society where dimensions of education reach into, and change, nearly every facet of human life.” He adds that “formal education…has become such an extensive undertaking that society is influenced by its logic and ideas more than the other way around, and this has been so for some time.” This education, he continues “transforms individuals…but also produces a widespread culture of education having the legitimate power to construct new types of minds, knowledge, experts, politics, and religions.” The result is a “massive secular faith in education along with frustration at unmet, albeit unrealistic, grand expectations.” At the root of this change is the university, particularly “over the past fifty years by a supercharged form of the research university and mass higher education. The university, then, is “perhaps the single most dynamic creator of cultural understandings in postindustrial society.” [2]

Schudson rests, or begins, his “critical culture” argument on Baker’s book, even while connecting it to names more familiar to USIH readership: Clark Kerr, Thomas Bender, Carl Schorske, Christopher Jencks, David Riesman, and Jamie Cohen-Cole. Schudson uses these scholars to underscore the “growth and transformation of higher education” in the postwar landscape. He wants to show how that octopus has become “a major force of social change.” [3]

Kerr is used to give Schudson fundamental numbers about increased student enrollments and federal research dollars. Bender and Schorske help Schudson argue for “a narrowing of the variety of institutional missions” such that there came into being “a single national system of ‘higher education’ with research universities at the top, setting the standards and…the pace” for all other institutions. Jencks and Riesman buttress, in Schudson’s hands, Bender and Schorske by showing that faculty more than presidents or boards of trustees in causing institutional quality to be “measured on a single gradient”—i.e. deference to a “small set of PhD-granting institutions.” Schudson the uses Bender and Cohen-Cole to argue that science and the scientific ethos set the standards for “critical inquiry,” displacing the formerly ascendant humanities. This also caused a shift in subjects studied, in favor of the present period and the United States—but all under the broad ethos of science.[4]

Schudson caps the scholarly underpinnings of his “critical culture” argument with Cohen-Cole. The former wholeheartedly buys the latter’s thesis that “the ‘open-minded self’ became the model person in academic society”—that “open-mindedness came to be seen as a core attribute of citizens” during the Cold War. This set up a dichotomy in relation to the vision of the Soviet Union as a “closed” society. Using the 1945 Harvard “Red Book” as the pivot point, a new model of “general education” would supersede the old paradigm of a shared, common knowledge. At the center of this new general education was the scientific ethos, seen then as organized around the “shared skills of effective thinking, judgment, communication, and the ability to ‘discriminate among values’.” [5]

Schudson caps the scholarly underpinnings of his “critical culture” argument with Cohen-Cole. The former wholeheartedly buys the latter’s thesis that “the ‘open-minded self’ became the model person in academic society”—that “open-mindedness came to be seen as a core attribute of citizens” during the Cold War. This set up a dichotomy in relation to the vision of the Soviet Union as a “closed” society. Using the 1945 Harvard “Red Book” as the pivot point, a new model of “general education” would supersede the old paradigm of a shared, common knowledge. At the center of this new general education was the scientific ethos, seen then as organized around the “shared skills of effective thinking, judgment, communication, and the ability to ‘discriminate among values’.” [5]

Having mixed together this scholarly foundation about changes in academia, Schudson kneads it further. He acknowledges that these historical transformations (“from religious to secular, from recitation and drill to critical inquiry, ..to the promotion of ‘the power of independent inquiry'”, etc.) began in the late nineteenth century. But he believes it all “accelerated greatly after 1945.”[6] And then he ties it all together in a singular grand statement—one that will interest every single intellectual historian and which provides a key assumption for his entire book:

And it makes sense to me, even though I cannot demonstrate it, that the changes in higher education undergird every postwar development in greater openness, greater criticism, freer dissent, and a presumption that there is a right to know in democratic culture, if not in the U.S. Constitution. …Meanwhile, and perhaps most important of all, what a college degree had come to stand for by the 1960s was experience in and a belief in critical thinking. Academic culture itself, like journalism, adopted “adversarial” habits.[7]

II.

There is obviously a lot to unpack in that passage. My first reaction, during a reading for a review that will appear in American Studies Journal this summer, was that Schudson’s view of higher education and its effects was, well, Panglossian. However, I didn’t mention higher education in my relatively brief review for couple of reasons. First, there is a lot to like in Schudson’s book. And I wanted to relay those positives to my review readers. Second, I critiqued a larger omission (i.e. anti-intellectualism and the anti-knowledge establishment) that helps explain why I feel that Schudson’s thesis was optimistic. Third, I wanted to dwell further on Schudson’s arguments about higher education and larger “critical culture”—which is I’m writing today.

Now that I’ve had plenty of time for dwelling, I do not find either narrative compelling. I find the larger “critical culture” argument plain wrong, but I have sympathies for viewing higher education as a positive force, as a vanguard, for efforts to create critical culture. I am unconvinced in relation to the time frame Schudson addresses in his book, but also in how he leaves his argument as still applicable for the present.

On a larger postwar “critical culture,” first, Schudson does not examine enough cultural institutions or higher education institutions to prove this point. He admits the latter in the paragraph above, but doesn’t really admit the former in the rest of the book. He relays the phrase and assumes it, but only defines it, historically, in relation to politics, political culture, and journalism. In my own formal review I didn’t criticize Schudson’s thesis in relation to those topics because it is objectively true that all three aspired toward more transparency in the 1945-1980 period. Schudson has convinced me of that. But those positive transformations will not necessarily result in a more critical culture. And Schudson knows it, hence the side argument about higher education. He felt the need to buttress his larger assertion.

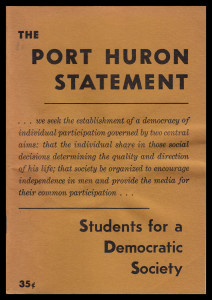

When one looks closer at higher education, during Schudson’s period of study (1945-1980), I still find his argument unconvincing or mixed at best. On students, evidence abounds of students and administrators criticizing the motives of students. One need only look at the Port Huron Statement, produced in 1962 by Students for a Democratic Society, for evidence to the contrary. The authors of that statement asked that cultural and educational institutions “be generally organized with the well-being and dignity of man as the essential measure of success.”[8] Let’s attend to their criticism of education, as articulated by the primary author, Tom Hayden, relative to the 1950s and early 1960s. What follows is a long (apologies!) but edited excerpt—bolds mine to emphasize analysis at odds with Schudson:

When one looks closer at higher education, during Schudson’s period of study (1945-1980), I still find his argument unconvincing or mixed at best. On students, evidence abounds of students and administrators criticizing the motives of students. One need only look at the Port Huron Statement, produced in 1962 by Students for a Democratic Society, for evidence to the contrary. The authors of that statement asked that cultural and educational institutions “be generally organized with the well-being and dignity of man as the essential measure of success.”[8] Let’s attend to their criticism of education, as articulated by the primary author, Tom Hayden, relative to the 1950s and early 1960s. What follows is a long (apologies!) but edited excerpt—bolds mine to emphasize analysis at odds with Schudson:

If student movements for change are rarities still on the campus scene, what is commonplace there? The real campus, the familiar campus, is a place of private people, engaged in their notorious “inner emigration.” It is a place of commitment to business-as-usual, getting ahead, playing it cool. It is a place of mass affirmation of the Twist, but mass reluctance toward the controversial public stance. Rules are accepted as “inevitable”, bureaucracy as “just circumstances”, irrelevance as “scholarship”, selflessness as “martyrdom”, politics as “just another way to make people, and an unprofitable one, too.”

Almost no students value activity as a citizen. Passive in public, they are hardly more idealistic in arranging their private lives: Gallup concludes they will settle for “low success, and won’t risk high failure.” There is not much willingness to take risks (not even in business), no setting of dangerous goals, no real conception of personal identity except one manufactured in the image of others, no real urge for personal fulfillment except to be almost as successful as the very successful people. Attention is being paid to social status (the quality of shirt collars, meeting people, getting wives or husbands, making solid contacts for later on); much too, is paid to academic status (grades, honors, the med school rat-race). But neglected generally is real intellectual status, the personal cultivation of the mind.

“Students don’t even give a damn about the apathy,” one has said. …

Under these conditions university life loses all relevance to some. Four hundred thousand of our classmates leave college every year.

But apathy is not simply an attitude; it is a product of social institutions, and of the structure and organization of higher education itself. …The bounds and style of controversy are delimited before controversy begins. The university “prepares” the student for “citizenship” through perpetual rehearsals and, usually, through emasculation of what creative spirit there is in the individual.

… Further, academia includes a radical separation of student from the material of study. That which is studied, the social reality, is “objectified” to sterility, dividing the student from life — just as he is restrained in active involvement by the deans controlling student government. The specialization of function and knowledge, admittedly necessary to our complex technological and social structure, has produced and exaggerated compartmentalization of study and understanding. This has contributed to: an overly parochial view, by faculty, of the role of its research and scholarship; a discontinuous and truncated understanding, by students, of the surrounding social order; a loss of personal attachment, by nearly all, to the worth of study as a humanistic enterprise.

There is, finally, the cumbersome academic bureaucracy extending throughout the academic as well as extracurricular structures, contributing to the sense of outer complexity and inner powerlessness that transforms so many students from honest searching to ratification of convention and, worse, to a numbness of present and future catastrophes. The size and financing systems of the university enhance the permanent trusteeship of the administrative bureaucracy, their power leading to a shift to the value standards of business and administrative mentality within the university. Huge foundations and other private financial interests shape under-financed colleges and universities, not only making them more commercial, but less disposed to diagnose society critically, less open to dissent. Many social and physical scientists, neglecting the liberating heritage of higher learning, develop “human relations” or morale-producing” techniques for the corporate economy, while others exercise their intellectual skills to accelerate the arms race.

Tragically, the university could serve as a significant source of social criticism and an initiator of new modes and molders of attitudes. But the actual intellectual effect of the college experience is hardly distinguishable from that of any other communications channel — say, a television set — passing on the stock truths of the day. Students leave college somewhat more “tolerant” than when they arrived, but basically unchallenged in their values and political orientations. With administrators ordering the institutions, and faculty the curriculum, the student learns by his isolation to accept elite rule within the university, which prepares him to accept later forms of minority control. The real function of the educational system — as opposed to its more rhetorical function of “searching for truth” — is to impart the key information and styles that will help the student get by, modestly but comfortably, in the big society beyond. [9]

Do we take the “Port Huron Statement” at its word? Of course not. Was it a carefully researched sociological study reflective of the students of its day? No. It was produced by a minority of students, probably all white males, early in the 1960s, and written from a certain political vantage point (i.e. those desiring revolutionary changes).[10] Of course Tom Hayden was an intellectual and an activist—not representative of the common run of college students in his day. Yet, fueled by the “Port Huron Statement,” SDS did things outside of, and about, academia to bring about the sentiments expressed in the manifesto. Although the organization grew slowly, it exploded around 1965 when anti-war sentiment escalated. It counted 2500 members in December 1964, but 25000 by October 1966.[11]

Although the group’s leadership and focus changed by 1966, the popular group’s criticism of universities did not. Note this passage from Geoff Bailey’s 2003 history of SDS (bolds mine):

The paper that defined the new direction for SDS was written by Carl Davidson and was titled, “A Student Syndicalist Movement: University Reform Revisited.” The paper took up the criticisms of the university that had been part of the Port Huron Statement and developed them in a much more radical direction. The universities “produce the know-how that enables the corporate state to expand, to grow and to exploit more efficiently and extensively both in our own country and in the Third World,” wrote Davidson. “Without them, it would be difficult to produce the kind of men that can create, sustain, tolerate and ignore situations like Watts, Mississippi and Vietnam.”22 A radical student movement that focused on student control of the universities, Davidson argued, could be the basis for a new radical movement for much wider social transformation. [12]

Even apart from this evidence offered about SDS in the 1960s, I know of no other historian of higher education that support’s Schudson’s thesis. None of those historians has clearly attributed the creation of a larger “critical culture” in the U.S. to higher education.[13]

III.

With something of counter narrative in hand from primary sources, we can suspect that higher education, while perhaps participating in the broader movement to create David Baker’s “schooled society,” did not also unambiguously foster the creation of a “critical culture” in the 1960s.

Indeed, on Baker, I haven’t read all of the book (yet!), but I can find no instance of him arguing that a larger “critical culture” results from a “schooled society.” Baker notes that an “academic driven epistemology” has resulted in school curricula that emphasizes “the culture of cognition, ” “the culture of science,” and “universalism.” The first, which I think comes closest to Schudson’s argument, is said by Baker to foster “mental problem-solving, effortful reasoning, abstraction and higher-order thinking, and the active use of intelligence.” These being the “explicit, overarching epistemological leitmotif of modern education,” have intensified in “importance both within and without schools and universities.” [14]

This could lay the groundwork for a “critical culture” in they future, but the “culture of cognition” is not indicated by Baker to be in substantial existence even in advanced societies. Those are currently curricular goals and objectives. So Baker, it seems, as a theorist of the recent past and present, doesn’t really support Schudson’s historical argument (particuarly in the 1945-1980 period). I offer that provisionally as I continue my reading in The Schooled Society.

What of other cultural institutions? If a “critical culture” existed in the United States, how was it fostered? Was it nurtured by the imparting of critical thinking skills, or by the dissemination of information? And, the last and biggest question of all: What of all the factors and institutions that inhibited the creation of a critical culture in the postwar era? What of the powers of what some scholars subsume under ‘anti-intellectualism’? Or conservative think thanks? Or agnotology?

Apart from the faulty power Schudson gives to higher education, it is his underestimation of the forces arrayed against deep, substantial, and engaged criticism that make his thesis Panglossian. – TL

————————————–

[1] Michael Schudson, The Rise of the Right to Know (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2015), 109-10, 170-176, 303n11

[2] David P. Baker, The Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global Culture (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2014), xi, xii, xiv (bolds mine).

[3] Schudson, 170, 303n11, 311n62-70. Schudson incorrectly cites Baker’s name as “Brady” in the text.

[4] Ibid., 170-173.

[5] Ibid., 173-174

[6] Ibid., 175

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Port Huron Statement of the Students for a Democratic Society” (June 1962).

[9] Ibid.

[10] I’ve never looked into the demographics of attendees nor the writing process at that June 1962 meeting.

[11] Geoff Bailey, “The Rise and Fall of SDS,” International Socialist Review 31 (Sept-Oct 2003). Available here

.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Not Roger Geiger’s The History of American Higher Education (2015), nor his forthcoming book on the same (mentioned in final paragraph), nor Julie Ruben’s The Making of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality (1996).

[14] Baker, 190-191.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Tim, thanks for this post. So much to unpack here — besides what you have unpacked already!

One thing that strikes me in your description of both Schudson’s and Baker’s argument is the division between “the university” and “society,” or “the university” and “culture.” I understand that’s it’s a heuristic division, believe me — but I think it often gets in the way of seeing the underlying unifying (though certainly not uniform) sensibilities of a time. Perhaps part of the difficulty with Schudson’s causal argument (and maybe Baker’s too) lies in looking at changes in/to the university as the source of particular changes in the broader culture, rather than as symptomatic of deeper general shifts that are for various reasons particularly visible/salient in the university.

On the connection between “critical thinking,” a scientific outlook, and the relative devalorization of the humanities within the university — well, yes and no, I think. The changed conception of the ideal modal self that Jamie Cohen Cole traces is certainly there — from “genius” to “creativity” and “open-mindedness.” At the same time, though it was described in different terms, the elective system, Charles W. Eliot’s great curricular gift to us all, aimed at cultivating the deliberative judgment and critical capacities of students through the exercise of choice. The act of choosing was educative (following John Stuart Mill here), particularly and crucially for citizens in a deliberative democracy. So there’s a sense in which, even in the supposed heyday of the humanities, a university education was as much about “transferrable skills” as content. (I have written about this in an op ed which is now in the hands of an editor — if it gets published I’ll post a link. If it doesn’t get published, I’ll post it here at the blog instead.) But of course the elective system fits within the “changes since the late 19th century” idea of Schudson, and fits also within the rise of “scientific democracy” that Jewett has identified.

LD: Thanks for the comment! I had been wondering if anyone would have the patience to wade through my post.

On your first paragraph, I think Baker’s book will interest you. For Baker, our schools (K-12, colleges, universities) are, in fact, shaping our culture, society, and institutions in ways that we have not yet fully grasped. Our culture, to him, is less influencing our edu institutions than the other way around.

In that sense, then, if no critical culture has developed, or has been sustained, it is the fault of our schools. Baker’s argument about schools (who mimic university values) valuing a “culture of cognition” has not translated into fostering a “critical culture” beyond. Our edu institutions have not valued *that kind of culture* in relation to any of their curricular choices and requirements.

I look forward to reading your op-ed, wherever it ends up published! – TL

Tim, here is the piece I mentioned. On Lamentations for a Lost Canon. Tried to avoid oversimplification / reductive narrative, but what can you do with 1200 words. Still, this is, broadly, What I Think. YMMV.

Read it. Well done. I glossed it on my FB page, but won’t add it here because my points are off topic. – TL

An interesting post as always, Tim, and your identification of this view as Panglossian seems spot on.

It also seems important to unpack what we mean by “science” in the period between, say, 1930 and 1970. There is some healthy debate out there in the literature that points toward a more pluralistic view of how science is defined in the period, and I hope historians continue to unpack those definitions and meanings.

I would think those definitions would be one lynchpin to assessing whether higher education fostered a more critical or a more complacent outlook among students. We have Jewett’s scientific democrats, Isaac’s operationalists, Hollinger’s cosmopolitans, the religious humanists of the Humanist Manifesto — and that is just covering a certain subset of academics, a good number of whom were identified with the Northeast part of the country, and usually identified with a left-liberal middle way. The spectrum seems wider than that.

Bryan

Thanks for this comment, Bryan. Teasing out the meanings of science would go some way to helping determine if higher education was fostering any kind, if any, of a critical culture. – TL

Tim,

Thank you for the incisive review. I will have to read both Schudson and Baker.

I especially like your point about “other” institutions that either or inhibited or fostered critical culture. Now I wonder whether the buzz over the hetrodox academy isn’t just one such effort to suppress critical thinking in the name of both-sidesism

Being a splitter myself, I would lean away from even seeing, per Bryan, “science” per se (or its variants) as a producer of critical culture. This is because there has been a division of epistemological, methodological, and political styles within the several sciences where some approaches were “critical” in all senses and some less so.

As regards the question of whether the university produced a measure of critical culture or inhibited it — why not say it did both?

If the university produced the architects and apologists of the Vietnam war and of American consumer culture, what would SDS or the Port Huron statement have looked like without the existence of the university? Can’t we see the discussion of the university by SDS as a call for the academy to live up to some sort of ideal of what it supposed to be (in the imagination of SDS)? If so, what was the origin of the idea that the university had been perverted? If I remember correctly, Hollinger has argued the Free Speech movement involved calling for the university to be its true self. Is that right?

Where did folks in the FSM or like Hayden and Davidson or Paul Potter get these ideas of the true university or of true scholarship? What did they read, who did they talk to, which actual physical spaces provided the social and intellectual space for their critiques of the university and of America?

We know some (but not all) of this has the be university from its physical space to the forms of critique it fostered. And by fostered, I don’t mean that “the university” was a unified thing — only that there were spaces in universities which were conducive to critique.

Tim, I also think you make a very good point about the distance between the university and anything outside of it. Even if the university did help foster a form of criticism internally, there’s still a long way to showing that it was the seeds of such criticism (rather than those of other varieties of criticism) that bloomed outside the academy walls.

Thanks Jamie! My sense is that you’re correct about higher ed both fostering and inhibiting critical culture. I meant to convey that above, but didn’t, or at least didn’t clearly.

I’m looking forward to all the articles and books, forthcoming, that help us understand better what we all mean by terms like “critical thinking” and even “critical culture”—where and when it’s inculcated, how it degrades (if ever), etc. – TL