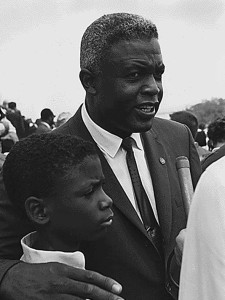

As a follow up to the great Jackie Robinson documentary shown on PBS last week, today I am going to create a brief list of works to read about Jackie Robinson, his legacy, and the America in which he lived. These works provide context for Robinson’s public stature. Jackie Robinson

, as a documentary, provides a fascinating look at American life in the twentieth century. These readings will provide further commentary. As always, feel free to add more in the comments section.

All Eyes Are Upon Us—Jason Sokol’s history of Northeastern liberalism provides wonderful context for Robinson’s career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. In Sokol’s book, he argues that the region that includes New York City, Boston, and New Jersey was forced to come to terms with its own history of racism and discrimination. In All Eyes Are Upon Us, Sokol includes a section on Brooklyn and the arrival of Jackie Robinson in 1947. Here, as with the rest of his book, Sokol frames the Jackie Robinson story within a larger framework of American liberalism and the Northeastern idea of tolerance. In addition, Timothy Thurber’s Republicans and Race offers an excellent primer on African Americans and the Republican Party before and during the period Robinson was politically active. Leah Wright Rigueur’s book, The Loneliness of the Black Republican, as mentioned last week, is indispensable as well.

“The Paul Robeson-Jackie Robinson Saga and a Political Collision” (Journal of Sport History, Vol. 6, No. 2, Summer 1979)—the Jackie Robinson documentary’s second episode featured what might have been Robinson’s most painful moment in the spotlight: his 1949 HUAC testimony against fellow African American celebrity (and athlete—Robeson was as a talented football player at Rutgers in the 1910s) Paul Robeson. While the documentary spends some time on Robinson’s HUAC testimony, it fails to mention Robeson’s starring role in the campaign to desegregate Major League Baseball. During the 1940s, this debate was embraced by American liberals and leftists alike. The prominent  Communist Party-backed newspaper, The Daily Worker, published numerous columns by its sports editor, Lester Rodney, calling for an end to the national pastime being segregated. Robeson himself addressed all the owners of Major League Baseball near the end of 1943, as part of a larger meeting on the issue of desegregation.[1] This piece not only puts Robinson’s testimony in context, but reminds us that Robinson admitted in his autobiography, I Never Had it Made, that he deeply respected Robeson as a person and as a champion for African Americans.[2]

Communist Party-backed newspaper, The Daily Worker, published numerous columns by its sports editor, Lester Rodney, calling for an end to the national pastime being segregated. Robeson himself addressed all the owners of Major League Baseball near the end of 1943, as part of a larger meeting on the issue of desegregation.[1] This piece not only puts Robinson’s testimony in context, but reminds us that Robinson admitted in his autobiography, I Never Had it Made, that he deeply respected Robeson as a person and as a champion for African Americans.[2]

Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson—Timothy M. Gay’s book offers a story not known by many of even the most hardcore of baseball fans. While it is accurate to say that Major League Baseball was segregated from the late nineteenth century until 1947, it would be wrong to say black and white baseball players—especially the professionals of MLB and the Negro Leagues—never interacted and played with each other on a baseball diamond. The book delves into the careers of Negro League, and later Major League, star Satchel Paige—along with the careers of St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Dizzy Dean and Cleveland Indians ace Bob Feller. All three participated in off-season games between Negro League and Major League players. This book shows the ways in which some Americans maneuvered around the color line in the early twentieth century.

I Was Right on Time—Buck O’Neil has become synonymous with the Negro Leagues. As a player there for many years, his stories about interactions with all the great stars of the league have become fodder for many baseball writers. This memoir, I Was Right on Time, is not just his remembrance of the Negro Leagues. It is one man’s journey through a segregated, but slowly changing America—and how that America looked to African Americans living and working in a segmented society.

I Never Had it Made–I would be committing a major error by not adding Jackie Robinson’s autobiography to this list. Not only does he discuss his playing career, but Robinson also discusses his own life of activism and political involvement after his baseball life came to an end. As intellectual historians, I believe it is important to read works like this one—to get a certain context for the middle of the twentieth century that includes race, politics, and even what it meant to deal with life as an American celebrity.

Finally, as an intellectual historian, I do think it intriguing to think about Robinson’s outsized stature within recent American history. In many ways he has, along with Martin Luther King, Jr., entered the hollowed cathedral of America’s newly diverse civil religion. Robinson has come to represent (and the documentary in many ways tried to counter this) a living embodiment of the “American Creed” written about by Gunnar Myrdal in An American Dilemma. The tying together of baseball, Cold War era civil rights rhetoric, and an upstanding citizen in Robinson have left behind the legacy of Jackie Robinson as an icon. Like King and Rosa Parks, Robinson as a symbol may prove–to historians at least–to be less interesting than Robinson the man, but for millions of Americans he is still an inspiration precisely because of his symbolic qualities.

Ronald A. Smith, “The Paul Robeson-Jackie Robinson Saga and a Political Collision,” p. 13.

[2] Smith, 23.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great stuff as usual Robert! Jules Tygiel has written a handful of books on baseball in general, and Jackie Robinson in particular. His biography of Robinson “Baseball’s Great Experiement” is still considered the standard.

I picked up a recent book (after seeing some of its authors on a conference panel) that looks interesting, but I doubt will be widely read (in part because it was self-published), called “42: Essays on the Intersection of Race, Class, Spirituality and Sport in the Jackie Robinson Story.”

I’m sure there are more great books on Robinson, and there definitely are more on the Negro Leagues and African Americans in baseball. How much the deal with intellectual history, I think, depends on how you read and interpret their theses. As you mention, I think Buck O’Neil’s legacy in remembering the Negro Leagues is important and if you read and listen to some of his stories you can explicate a larger philosophy on life and surviving segregated America. See, for example, Joe Posnanski’s “The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O’Neil’s America.”

Thanks for the recommendations. And you’re absolutely right–it really does depend how one reads these how important they are to any intellectual historian. The intersection of sport and intellectual history is important to getting at so many themes in American history, such as race, gender, regionalism, etc.