Monday and Tuesday of this week, PBS premieres a new Ken Burns miniseries, Jackie Robinson. I am excited by the prospect of a new work on Robinson’s life, primarily due to the tantalizing hope that Burns will spend time on Robinson’s post-baseball public life—and, according to this review in the New York Times, it looks like it will. Jackie Robinson led a publicly engaged life after his baseball career ended in 1956. In short, Mr. Robinson transitioned from baseball to, through a nationally syndicated column, the life of a public intellectual.

Robinson’s career, once he was called up to the majors in April, 1947, was never as easy as that of most American athletes. He always served as a representative of African Americans in public life. Recall, for instance, his testimony against Paul Robeson in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1949. Robinson deplored Robeson’s comments about African Americans not fighting the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. Robinson would later regret his dismissal of Robeson in his autobiography, I Never Had It Made. Robinson would have other public avenues to express his political and social beliefs. His column, titled “Jackie Robinson Says,” started when his career with the Brooklyn Dodgers took off in 1947. After his playing days were over, Robinson took on a wide variety of issues affecting not just African Americans but the American people in general.

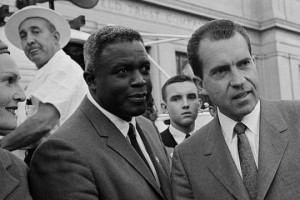

Jackie Robinson’s stalwart Republicanism is also important to keep in mind here. Robinson’s support for the Grand Old Party was part of a long African American political tradition, stretching back to the Reconstruction era, of backing the party of Lincoln. This  was not blind obedience to the Republican Party. Instead, Robinson (like many other African American voters) weighed carefully the choices they had between the Republican and Democratic Parties. From the New Deal era of the 1930s until the nomination of Barry Goldwater by the GOP in 1964, both parties included strategists who debated the need for their party to get the African American vote and, by extension, key battleground states in national elections.

was not blind obedience to the Republican Party. Instead, Robinson (like many other African American voters) weighed carefully the choices they had between the Republican and Democratic Parties. From the New Deal era of the 1930s until the nomination of Barry Goldwater by the GOP in 1964, both parties included strategists who debated the need for their party to get the African American vote and, by extension, key battleground states in national elections.

Robinson’s support for the Republican Party—tempered by a skepticism about its right-wing—were given full voice during the 1964 campaign. As Leah Wright Rigueur, historian and author of the fantastic book The Loneliness of the Black Republican, has argued, Robinson played a major role in the anti-Goldwater backlash within both the Republican Party and the African American community that gained steamed in the fall of 1964. Robinson, in several of his columns in the fall of 1964, warned of what would happen to the Republican Party if they embraced Goldwater. His support for the Republican Party, tempered by a willingness to criticize the party on issues of race, is something Rigueur emphasizes in her book.

Also, Robinson expressed skepticism about the Democratic Party’s leadership on civil rights. He expressed dissatisfaction with President Kennedy, for instance, on his leadership on civil rights in a 1963 column. “We are not as concerned about the top-level appointments for the Thurgood Marshalls and Robert Weavers, no matter how highly we regard them personally, as we are about the continuing day-to-day discriminations in jobs, housing and politics which confront the Negro masses,” he wrote in 1963.[1] Robinson’s example as a columnist in the Chicago Defender (and syndicated elsewhere) brings to mind the diversity of thought among African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s who worried about both Southern segregationists in the Democratic Party and right-wing conservatives in the Republican Party, seen as the two biggest threats to civil rights legislation in Washington.[2]

Robinson also had no qualms about criticizing African American civil rights leaders. For example, he expressed astonishment with Martin Luther King Jr.’s stance on the Vietnam War in 1967. Robinson argued, “I know that our country is not always right  and that, in fact, on the domestic front, our country has been and is so terribly wrong with respect to its treatment of the Negro,” he wrote. But continuing, Robinson stated, “But, Martin, aren’t you being unfair when you place all the burden of blame upon America and none upon the Communist forces we are fighting.”[3] Robinson’s column was a place for him to critique—not due to personal avarice but through genuine concern—civil rights leaders throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

and that, in fact, on the domestic front, our country has been and is so terribly wrong with respect to its treatment of the Negro,” he wrote. But continuing, Robinson stated, “But, Martin, aren’t you being unfair when you place all the burden of blame upon America and none upon the Communist forces we are fighting.”[3] Robinson’s column was a place for him to critique—not due to personal avarice but through genuine concern—civil rights leaders throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

This is a small sampling of the issues Robinson wrote about in his “Jackie Robinson Says” columns. The former baseball star tackled civil rights, the Cold War, and national politics during an era of American history where all three of those issues caused a multitude of national crises. Robinson deserves to be remembered not just for his playing career, but for his willingness to stay in the public spotlight and talk about issues of race and American democracy.

[1] “Jackie Robinson Says,” Chicago Defender, June 30, 1962, p.8.

[2] For example, Martin Luther King, Jr. expressed frustration with the GOP for nominating Goldwater on numerous occasions. From Where Do We Go From Here: “Its 1964 disaster with Goldwater, in which fewer than 6 percent of Negroes voted Republican, indicates that the illustrious ghost of Abraham Lincoln is not sufficient for winning Negro confidence, not so long as the party fails to shrink the influence of its ultra-right wing (155).”

[3] Jackie Robinson, “An Open Letter to Dr. Martin L. King,” The Chicago Defender, May 13, 1967, p. 10.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Robert,

Are you aware of any comments/columns penned by Robinson concerning evolution (or, for that matter, any articles/books that discuss the evolution debates of the twentieth century within African-American communities)?

Mark

You know, I saw your question earlier today and did a little bit of research. So far I’ve not found anything from Robinson about evolution–but as for evolution within the African American community, I’m definitely not done looking. I’ll try to dig up something in the next few days, at the latest.

Fascinating post, Robert! Thanks for illuminating this part of Jackie Robinson’s life. Do we have any sense of the letters to the editor/comments that Robinson received as a columnist?

Not off the top of my head–but the Chicago Defender’s archives are accessible through ProQuest. It would take a little bit of time, but one could search through that database to find that information.

What I’ve gleaned so far is, at least in some of the letters to the editor I’ve glanced at, is support for Robinson. But I’m keen to look deeper into that–especially around 1966-67, when Robinson criticizes aspects of the Black Power movement. Black newspapers in the late 1960s were often critical of both MLK’s anti-war stance and the rise of Black Power. It’s something I definitely want to look into down the road.

Robert, funny that you should mention ProQuest! A couple of us USIH-ers met at OAH with the ProQuest developer who designed its “History Vault” database sets. He was interested in finding out from historians themselves (rather than, say, librarians, which is usually who ProQuest people interface with) what would be most useful/helpful in arranging/expanding those databases, and also wanted to know our thoughts on how to get the word out to historians who may not know all that is available. So I think some blog posts are coming here and elsewhere — but I would be very interested to know about your experiences in finding/using the archives available through ProQuest. (I believe they have NAACP archives, SNCC — a whole bunch of stuff.)