Last week I blogged about what I suggested was a disappearing character type: the psychopath as cultural rebel. This week I wanted to briefly respond to the very interesting comment thread that followed. In particular, I wanted to address Ray Haberski’s comment:

Last week I blogged about what I suggested was a disappearing character type: the psychopath as cultural rebel. This week I wanted to briefly respond to the very interesting comment thread that followed. In particular, I wanted to address Ray Haberski’s comment:

I wonder if I am thinking about your type in a different way. I find the intellectual psychopathic hero quite alive and well–see American Psycho, Fight Club, most of Tarantino’s films, the Dark Knight (to some degree), and Dexter.

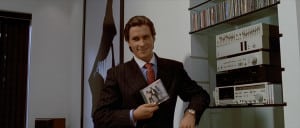

Clearly Americans still love psychopathic characters. But there’s an essential difference between the figures I wrote about last week, e.g., Mailer’s White Negro and Styron’s Nat Turner, on the one hand, and, say, American Psycho

‘s Patrick Bateman, on the other. The former are rebels, whose psychopathy was an expression of their rejection of the dominant culture. Patrick Bateman is precisely the opposite, a Wall Street master-of-the-universe, whose psychopathy is an expression of that dominant culture. Bateman’s psychopathy suggests that psychopaths run America.

As Dwight Garner recently noted in the New York Times, when Bret Easton Ellis published American Psycho in 1991, the book was met with outrage and overwhelming critical disdain. It was seen as crude and over-the-top. But in part due to Mary Harron’s extraordinarily effective film adaption of American Psycho (2000), the book has retroactively become a hit. It’s now been adapted into a musical. And the key to the movie – and the changing fortune of American Psycho – is that we have come to see that “American Psycho looks a lot like us.”

In 1999, just before Harron’s movie revitalized American Psycho, The Sopranos debuted on HBO, bringing us, in Tony Soprano, another arguably psychopathic character whose life was an allegory of mainstream American success. The Sopranos were not rebels, but rather upper middle-class New Jersey suburbanites. And Tony was in many ways a traditionalist, running a family business in the face of changing times.

Dexter and Tarantino’s psychopathic characters — say Lt. Aldo Rain (Brad Pitt) and his men in Inglourious Basterds (2009)) – are somewhat different from Patrick Bateman and Tony Soprano. They are closer to rebels. They’re certainly not representatives of anything that looks like the establishment…or rather to the extent that they are – the Basterds are in the military; Dexter Morgan is a police blood-spatter expert – their looks are deceiving. But their psychopathy is in the service of order and the good. Dexter only kills fellow psychopaths. Aldo Rain and the Basterds play a key role in ridding the world of Nazism. They are much more the cultural offspring of Dirty Harry than of the White Negro.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks, Ben! I always enjoy our conversations at the blog. So I bet you are also at work tracing how the rise of the blockbuster in the 1970s and 1980s buried whatever residual effects hip culture might have had on American film. At least our buddy J. Hoberman argued (and Jefferson Cowie echoes) that law and order entered American film with Dirty Harry and Star Wars and never left.

I have to end with a plug for my favorite psychopath in movies, Javier Bardem’s Anton Chigurh, who makes Woody Harrelson (famous for his psychopath NBK) look meek in No Country for Old Men.

Great piece. I would be interested in seeing how you think that these cultural critiques [though sadly with comic figures such as Deadpool (clearly psychopathic) and the Punisher (arguably such) missing] complicate discusssions of morality and ethics such as R.J. Smith’s The Psychopath as Moral Agent (1984) and more recent questions of psychopathy as supra-moralistic based on their observed higher levels of rationality.