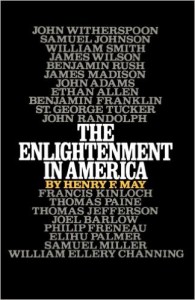

Henry F. May. The Enlightenment in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976)

Classics Review by Drew Maciag

If ever there was a classic of American Intellectual History, Henry May’s Enlightenment in America (EIA) is it. The book won the OAH’s very first Merle Curti Award in 1977 along with the AHA’s Albert Beveridge Award; it was widely reviewed and has been routinely cited for decades; apparently the book never stops selling—my own copy (purchased many years ago) is a ninth printing of the paperback edition! Moreover, it has become one of those benchmark books to which others are compared, and possibly because May got there “fustest with the mostest” he did not get much competition on the topic for a generation.[1] By the 1970s a major study of the subject was long overdue; May observed that although most historians were “partisans of the Enlightenment: of liberalism, progress, and rationality…there is no good book on the Enlightenment in America, indeed, no general book at all.”[2] Coincidentally, three related titles were published at about the same time as EIA, but none equaled May’s book in their impact or longevity of influence.[3]

Yet right from the start EIA (while receiving mostly positive reviews) was criticized for its overly schematized approach, its emphasis on taxonomic classification and its subdivisions of Enlightenment thought, as well as for its nullifying conclusion.[4] May likewise drew fire for assuming that the Enlightenment traveled only from the Old World to the New, that it contained no indigenous American components. Criticisms that increased over time, for instance that May included very few women or that his approach was elitist, had also surfaced early. Perhaps most telling, one reviewer expressed disappointment  over the failure of EIA, despite May’s enormous effort, to offer a more satisfying conclusion. In effect, May’s magnum opus was accused of punching below its weight, of settling for impressive chronicle instead of rising to imaginative insight. Over the years others have testified that the major impression left by EIA was the amount of work that May poured into it—hardly a compliment befitting a classic, yet the feeling is understandable. Because the book was so encyclopedic in its coverage, and because most scholars had a stake in how its iconic subject was portrayed, EIA was always as easy to knock as to praise.

over the failure of EIA, despite May’s enormous effort, to offer a more satisfying conclusion. In effect, May’s magnum opus was accused of punching below its weight, of settling for impressive chronicle instead of rising to imaginative insight. Over the years others have testified that the major impression left by EIA was the amount of work that May poured into it—hardly a compliment befitting a classic, yet the feeling is understandable. Because the book was so encyclopedic in its coverage, and because most scholars had a stake in how its iconic subject was portrayed, EIA was always as easy to knock as to praise.

I think the book deserves both. But since my knocking points are unoriginal let me spend the limited space remaining on what I appreciate about EIA

, and why I believe the book is still worth reading. In the course of my own development as a historian I came to realize that although EIA was not a book I could love, it was a book I could learn from—and I hope I have.

This raises an issue that has special meaning for me as a mid-life career-changer. I remember my surprise when one of my professors told me (as a first-semester, 41-year-old Ph.D. student), that I was bringing up too many “older” books during seminar discussions, and that scholars generally focused on writings published in their fields within the last ten years (which were virtually the only titles the younger grad students seemed to be aware of). So my question is, why read “old-fashioned” classics in the first place? My answer is that lessons can be learned from them that cannot be learned as readily or as authoritatively elsewhere: they became classics because they had something exceptional to offer. This rule is not unique to the writing of history. Why for example should a film student watch Citizen Kane or any old-style film of the sort that will never be made again? Why should budding novelists bother to read Hemingway or Jane Austen? The objective of exposure to the first-rate work of prior periods is to develop an understanding of the skill and (as important) an appreciation of the vision of its creator; the practical goal is not to imitate it, but to absorb its timeless qualities.

In the case of May and EIA there were several successful techniques on display. For instance, May had an unusual talent for drawing thumbnail sketches of historical figures that not only captured their intellectual outlooks, but also tied them to the larger philosophical or sociological culture he believed they represented. Such passages worked best when read in context, in order to grasp their thematic connections and subtle implications; yet even when read independently it was obvious how much information and interpretation May was able to pack into a few sentences. More impressive still, his sentences flowed nicely; they were smooth, clear, and well-integrated into the surrounding text.[5] Such efficient and effective writing is more difficult to pull off than one might think; I would compare it to writing a good haiku or limerick. Furthermore, the cumulative effect of EIA’s highly polished character sketches underscored the methodological reality (at least as May saw it) that the intellectual history of an age—especially when dealing with such abstract constructions as the Enlightenment—was to a large degree a compendium of biographical soundings. After all, where else would one find “an Enlightenment” other than in the minds of its participants or its later-day historians, advocates, or critics?

Another of May’s strengths was his ability to crystallize the mood of an era or a phenomenon of mass psychology. The first few pages of each section of EIA offered compact overviews of historical moments or of particular conditions or trends; these “macro-passages” provided context for the numerous “micro-studies” that followed, and they also supplied a dose of stylistic balance. [6] Clearly May excelled at painting both the forest and the trees; whether or not he was able to combine them into an entirely satisfying historical landscape was a different matter. Despite May’s technical and literary virtuosity, EIA

remains more impressive than it is convincing. While one cannot easily challenge May’s knowledge or his specific evidence, it is difficult for most readers today to accept his book as the true or complete or even the most plausible story of the Enlightenment in America. Perhaps this can be explained by examining May’s historical vision, or even speculating about his sense of mission.

May was open about the personal influences (autobiographical and psychological) behind his historical scholarship. Although he avoided crude presentism, his attraction to the American past grew out of an impulse to understand his environment. He also acknowledged his tendency toward ambivalence, his sense of not belonging, and his ultimate reliance on intuition.[7] Such predispositions worked against the simplicity, linear progressivity, and triumphalism of the “Empire of Reason” mythology that EIA debunked. Furthermore, EIA was a product of generational angst. Today one cannot help but notice a hint of late-consensus desperation in the book’s attempt at dampening the radical potential of an ongoing Enlightenment ethos. And because it was constructed during an instant of professional concern that cliometricians might remake historiography, May’s endeavor to support his insights with voluminous, hyper-classified examples is understandable. Above all, in tackling one of the greatest of all national themes (akin to Democracy, Progress, Freedom, and Exceptionalism), May helped reinvigorate an enquiry into American ideals at precisely the time American idealism was succumbing to fatigue.

Forty years after EIA’s publication the book—despite its flaws—still cannot be ignored by anyone writing on the subject. Like it or not, that’s one practical definition of a classic!

Drew Maciag is author of Edmund Burke in America: The Contested Career of the Father of Modern Conservatism (Cornell, 2013); he is currently working on two book projects, tentatively entitled: “John F. Kennedy and the Quest for Modernity,” and “Too Much of Nothing: America in the 1970s.”

[1] An excellent discussion of May’s Enlightenment in America that incorporates recent writings on the topic is: John M. Dixon, “Henry F. May and the Revival of the American Enlightenment: Problems and Possibilities for Intellectual and Social History,” William and Mary Quarterly 71:2 (April 2014), pp. 255-280.

[2] Henry F. May, The Enlightenment in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976; paperback 1978), xii.

[3] Earnest Cassara, The Enlightenment in America (Boston: Twayne, 1975), Donald H. Meyer, The Democratic Enlightenment (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1976), and Henry Steele Commager, The Empire of Reason: How Europe Imagined and America Realized the Enlightenment (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1977).

[4] For those unfamiliar with EIA, here is a brief tour: (1) May viewed the Enlightenment as an essentially European phenomenon transplanted to America. (2) On both sides of the Atlantic new ideas enjoyed influence mostly within educated urban circles rather than among the agrarian masses, hence enlightenment was a top-down process. (3) The Enlightenment unfolded in four successive (yet overlapping) stages—the Moderate, the Skeptical, the Revolutionary, and the Didactic—beginning as far back as 1690 and persisting to 1815 or 1825. (4) Particular Americans could be identified with each of the four schools of thought. May presented most of his evidence in the form of mini (or micro) intellectual biographies of 355 distinct persons, using their writings, speeches, letters, or sermons to explain how and why each of them fit into one of his retrospective categories. (5) In America enlightened thought had to compete with Calvinist Protestantism. Ultimately the Enlightenment failed to displace Protestantism as the nation’s dominant “cluster of ideas,” although elements of enlightened thinking—especially the Common Sense of the Didactic school—were assimilated into Protestant culture. (6) The endgame combination of Protestant morality and common-sense philosophy provided a framework for the nineteenth-century Genteel Tradition that dominated middle-class culture until the early twentieth century (thus linking EIA to May’s other classic book, The End of American Innocence, 1959).

[5] Examples can be found almost at random; see May’s forty-word description of the English essayist Joseph Addison (p. 37).

[6] A good example: May’s paragraph on American anti-Jacobinism (p. 252).

[7] See Henry F. May, Coming to Terms: A Study in Memory and History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), esp. 307-310.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Ditto on the John Dixon review essay in the April 2014 WMQ. I believe that May discusses Bishop George Berkeley largely in posthumous dialogue with Locke and Hume. I wonder whether more attention to Berkeley in the colonial Americas would’ve strengthened, or undermined, May’s categories and Protestant “cluster of ideas,” esp. in his treatment of Samuel Hopkins and later New England “New Divinity Men” (ala Richard Birdsall). I enjoyed the reconsideration.

BTW no relation to UST History Dept. Chair Catherine Cory

What I remember of reading May’s book a lifetime or two ago is how unconvincing it was. It just felt off somehow, as though it could never get its sums right. I agree with the critics about it being overly schematic and “potted,” to borrow a term from the English. I kept waiting for May to tell me how the Enlightement in America related to the one in Europe and he never did. Not to my satisfaction, anyway. It’s not a very good book, but as Dr. Maciag notes, it’s quite influential. I much prefer Robert Ferguson’s American Enlightenment. Darren Staloff’s recent book is good, too. But to my mind we’re still waiting for something on the American Enlightenment that’s comparable to Peter Gay or Jonathan Israel, or even, sticking to America, Gordon Wood.

“not a very good book” — now, that’s just straight-up contrarian trolling, Varad.

Contrarian? Yes. Trolling? No. I didn’t like it, and I’d be hard pressed to say a book I didn’t like is “very good.” Maybe “good.” But “very good”? Never. There’s a lot of useful information in it, but I didn’t find his conceptual framework convincing. And if you don’t buy that, you have a hard time buying the rest of it. So, yeah, “not very good.” Maybe I should just say it was “meh.” Now there’s a scholarly term of art if there ever was one!

For those waiting for a fresh book on the subject, Caroline Winterer (Stanford U.), American Enlightenments (Yale University Press) is forthcoming in fall 2016. Last year I attended her lecture: “Was there an American Enlightenment?” at the University of Rochester; if that “sampler” was any indication, her new book might resonate better with today’s readers (than Henry May’s classic treatment apparently does).

For sure. Her American Enlightenment exhibition and digital Republic of Letters project offered an array of sources to patrons and scholars alike.