This semester I’ve been leading an Honors College Reading Group on George Cotkin’s Feast of Excess. As many readers of this blog know, Cotkin’s book charts the rise of what both Tom Wolfe and Susan Sontag called “The New Sensibility,” a broad, cultural tendency toward excess – in both minimalist and maximalist forms – that Cotkin argues emerged in the 1950s, blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s, and remains strong today. Our Honors College reading groups usually tackle one book a semester, read slowly, most often thirty-five to fifty pages a week. Feast of Excess fits this pace perfectly, as it is divided into twenty-three short chapters, each focused on one year, starting in 1952 and ending in 1974, and on one, or occasionally two or three, cultural figures.

This semester I’ve been leading an Honors College Reading Group on George Cotkin’s Feast of Excess. As many readers of this blog know, Cotkin’s book charts the rise of what both Tom Wolfe and Susan Sontag called “The New Sensibility,” a broad, cultural tendency toward excess – in both minimalist and maximalist forms – that Cotkin argues emerged in the 1950s, blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s, and remains strong today. Our Honors College reading groups usually tackle one book a semester, read slowly, most often thirty-five to fifty pages a week. Feast of Excess fits this pace perfectly, as it is divided into twenty-three short chapters, each focused on one year, starting in 1952 and ending in 1974, and on one, or occasionally two or three, cultural figures.

Of course one reads a book differently when one reads at this slow pace. Patterns emerge that one might not otherwise notice. And one pattern struck me this week, as got to Chapter 16, which focuses on 1967, William Styron, and his controversial historical novel The Confessions of Nat Turner: the rise and fall of the idea of the psychopath as a cultural hero.

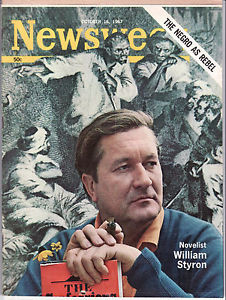

Styron saw Nat Turner, the leader of one of the most famous slave rebellions to take place in the United States, as a hero, but also “very definitely a psychopath.”[1] Styron’s book won a Pulitzer prize and garnered the author a Newsweek cover. And both his friend James Baldwin – who had supported the project since its inception – and Ralph Ellison praised the book. But many other African American writers and critics condemned it, culminating in the publication in 1968 of the highly critical collection William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond.[2]

As Cotkin notes, Styron’s book was written in the wake of Stanley Elkins’s Slavery(1959), which had superseded the once-dominant work of U.B. Philips, who had largely defended the institution of slavery as fairly mild and civilizing in its effects on the enslaved. In contrast, Elkins understood slavery through the lens of Bruno Bettelheim’s work on Nazi concentration camps. For Elkins, slavery was a brutal institution that utterly destroyed the humanity of enslaved Africans and African Americans, robbing them of their culture and infantilizing them in the process. Styron’s deeply psychological damaged Nat Turner was very much an intellectual child of Elkins’s vision of slavery.

But he was also, it seems to me, a cousin of Norman Mailer’s “white negro,” the subject of an earlier chapter of Cotkin’s book. The hipster existentialists that are the subject of Mailer’s 1957 essay “The White Negro,” which originally appeared in Dissent, are, above all, psychopaths, a term that Mailer defines through the work of juvenile delinquency experts Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck and of Robert M. Lindner, whose book Rebel Without A Cause: The Hypnoanalysis Of A Criminal Psychopath

(1944), lent its name, if little else, to the now better remembered James Dean film. Mailer’s essay is in large measure a celebration of the psychopath who,

may indeed be the perverted and dangerous front-runner of a new kind of personality which could become the central expression of human nature before the twentieth century is over. For the psychopath is better adapted to dominate those mutually contradictory inhibitions upon violence and love which civilization has exacted of us, and if it be remembered that not every psychopath is an extreme case, and that the condition of psychopathy is present in a host of people including many politicians, professional soldiers, newspaper columnists, entertainers, artists, jazz musicians, call-girls, promiscuous homosexuals and half the executives of Hollywood, television, and advertising, it can be seen that there are aspects of psychopathy which already exert considerable cultural influence.

My sense is that the psychopathic hero had broader cultural purchase during the 1950s and 1960s, though he (and I do think he was generally gendered male) began to decline in significance, at least among serious intellectuals shortly thereafter. The many African American writers who objected strongly to Styron’s vision of Nat Turner-as-psychopath were part of the turn away from this idea.

Whatever happened to the psychopath as cultural hero? There have certainly been plenty of fictional psychopaths in American popular culture over the course of the almost half century since Styron published his novel, but most of them are antagonists or at best anti-heroes, like Freddy Kruger or Hannibal Lector. But there is one, less exalted quarter of our popular culture, in which the heroic psychopath is alive and well: the work of Insane Clown Posse, the wildly popular, if critically derided, hip hop duo. Like Norman Mailer in “The White Negro” and William Styron in Nat Turner, Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope of ICP are white Americans playing with African American culture. And (generally good-natured) psychopathy is at the heart of the act, down to their naming the record label they founded “Psychopathic Records.”

Whatever happened to the psychopath as cultural hero? There have certainly been plenty of fictional psychopaths in American popular culture over the course of the almost half century since Styron published his novel, but most of them are antagonists or at best anti-heroes, like Freddy Kruger or Hannibal Lector. But there is one, less exalted quarter of our popular culture, in which the heroic psychopath is alive and well: the work of Insane Clown Posse, the wildly popular, if critically derided, hip hop duo. Like Norman Mailer in “The White Negro” and William Styron in Nat Turner, Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope of ICP are white Americans playing with African American culture. And (generally good-natured) psychopathy is at the heart of the act, down to their naming the record label they founded “Psychopathic Records.”

But while Mailer and Styron met bitter and serious opposition from their intellectual opponents, ICP is more likely to inspire satire and ridicule. In the decades since “The White Negro” and The Confessions of Nat Turner, we’ve stopped taking the psychopath quite so seriously, whether as an object of broad social anxiety, as in Lindner’s Rebel Without a Cause, or as an object of cultural hope, as in Mailer’s “The White Negro.” But don’t tell that to a Juggalo.

____________________________________________

[1] Quoted in Cotkin, Feast of Excess, 232. Nat Turner is, incidentally, the protagonist of the new movie The Birth of a Nation, which won both the Audience Award and the Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival and which will be receiving its general release this October.

[2] One can get a sense of the tenor of the debate on the eve of the publication of this volume in this fascinating radio discussion about Styron’s book between the author, Baldwin, and the actor and activist Ossie Davis.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Excellent piece, Ben. The celebration of the psychopath among intellectuals is central. Think not only of the psychopath but of mental illness in general, as with Laing’s work on insanity. The point was to transcend or rebel against the straight-jacket of society. Alas, is the psychopath a dead issue? Might glance at the Presidential candidates of late to wonder if the psychopath or madman is still afoot in our collective psyche? Mailer’s heroes (indeed, like his own limitless ego) have gone mainstream!

Ben: I wonder if I am thinking about your type in a different way. I find the intellectual psychopathic hero quite alive and well–see American Psycho, Fight Club, most of Tarantino’s films, the Dark Knight (to some degree), and Dexter.

Also, by dealing with “psychopaths” we can better reevaluate the boundaries between conformity/nonconformity and rationality/irrationality. By the late 1960s, if we can believe the nonconformists/hippies/dropouts, questioning America’s intentions and goals was considered insane and irrational, right? – TL

Ben–Two brief comments on your interesting point about the “psychopathic hero.” Another addition to the list would be “Kit” Carruthers in Terence Malick’s great film “Badlands”(1973). Played by Martin Sheen, Kit was modelled on 1950s serial killer Charles Starkweather.

Second, there was an lead-off panel devoted to Styron’s “The Confessions of Nat Turner” at the SHA in 1968. The chair was C Vann Woodward and it included Robert Penn Warren, Ralph Ellison and Styron. As I remember it, Ellison begged off commenting on his friend Styron’s novel, claiming he hadn’t yet read it. But maybe I misremember. Do you know where he(Ellison) wrote in praise of “Nat Turner”?

Thanks,

Richard King

There’s a broader history here, folks. For instance, see: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/crv/summary/v040/40.2.genter.html