“I demand whether all wars, bloodshed and misery came not upon the creation when one man endeavored to be a lord over another?…And whether this misery shall not remove…when all the branches of mankind shall look upon the earth as one common treasury to all.” – Gerrard Winstanley, The New Law of Righteousness, 1649[1]

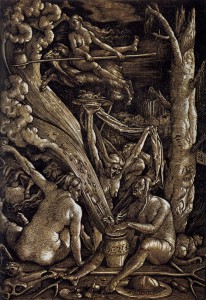

Recently I read Caliban and the Witch by Silvia Federici, a wonderful book that explores how the “transition to capitalism” (Federici always refers to the process in quotes, in order to emphasize her disagreement with the passive and seemingly natural evolution the phrase implies) involved and in fact required the degradation of women and the disciplining of their reproductive role. Hence the witch hunts, hence the criminalization of contraception, abortion, and prostitution.

Unlike many a book, Caliban and the Witch had not long sat neglected on my “need to read” list – in fact I had never heard of it before a casual conversation on Facebook about feminism and capitalism resulted in an acquaintance recommending it and me purchasing it merely minutes later. As regular readers of the blog know, this book has no direction connection to my own research, and the extent of my knowledge about the lived experience of the resistance to and “transition” away from feudalism consisted merely of a basic awareness of peasant revolts and a decent understanding of enclosure in England. Of everything before these processes, however, I was ignorant.

Amazingly, Federici addressed this very ignorance in the opening pages of the book. In her preface, she recounts teaching in an interdisciplinary undergraduate program where she “confronted a different type of ‘enclosure’: the enclosure of knowledge, that is, the increasing loss, among the new generations, of the historical sense of our common past.” With Caliban and the Witch, then, Federici hoped to “revive among younger generations the memory of a long history of resistance that is in danger of being erased.”[2]

In danger indeed! Reading Federici’s book felt like getting the inside scoop on a thousand events, processes, and personalities I had only been taught to consider in dry, isolated details, if at all. The first chapter deals with the struggle against feudalism, from common, daily acts of resistance which made the medieval village, as Federici writes, a “theatre of daily warefare,”[3] to the millenarian and heretic movements, phenomena which previously, had only been presented to me as specifically cultural and religious, rather than political or socio-economic, phenomena. Highlighting the calls for equality that, at times, even extended to radical ideas about gender relations, Federici argues that understanding these movements as political struggles is crucial to understanding that “Capitalism was the counter-revolution that destroyed the possibilities that had emerged from the anti-feudal struggle.”[4] From there, Federici focuses the majority of the book on how reducing the social power of women served both to undermine solidarity amongst peasants and artisans and, moreover, provided the state with the control over reproductive labor necessary to capitalist production.

While moving across these various contexts of different countries, centuries, and social movements, Federici actually keeps things in context – in the larger context of what, exactly, is happening here and why? And what do these various revolts and moments of resistance have in common, or not? By asking these structural questions, she opened up for me a whole swath of the historical past for consideration as something that happened in this world, to my ancestors. The feudal past was long ago and material and ideological reality was very, very different then – but yet, it isn’t Middle Earth or Westeros we are talking about here. It is planet Earth populated by human beings.

That’s certainly an inadequate summary of the book, but it is sufficient for asking this one question: how did I not know about this stuff? I was aware of the the witch hunt and heretical movements, of course, and never had the romantic notion that peasants really enjoyed being peasants or that acceptance to Catholic dogma was ever universal but still, it could not be said that I recognized the significance of pre-capitalist social struggle because I was never taught to. While always recognizing the limits of my empirical knowledge, I blithely assumed what I had been instructed to believe throughout my education, sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly: the pre-capitalist past, being so far away and belonging to such a different world than our own, does not really have anything to say to you – to assume any such relevance is to do violence to the past, to commit that sin of sins amongst historians, which is, of course, being ahistorical!

Thinking back on various moments in my education, I see the missed opportunities to expand beyond the narrow confines of a given seminar. Yes, when we studied the Salem witch trials we noted that the height of witch burning in Europe had died down by the late seventeenth century but had accompanied capitalist development – but that background context remained exactly that, a background. Federici, on the other hand, notes the specifically different dynamics at play in Salem but keeps the figure of the colonial witch in conversation with the early modern mindset of sectarian Protestantism that had developed, initially, in Europe. (In fact, my favorite moment in the entire book came with a quote from Cotton Mather about how he must strive to think holy thoughts while going to the bathroom, so to distance himself from this beastly necessity – of all the reasons to not romanticize the intellectual seriousness of Puritans, that has got to be near the top of the list.)[5] Similarly, I had studied the peasant revolts that occurred in the wake of the Reformation, but only insofar as we read Luther to understand how opposed he was, actually, to the interpretation of his new theology that the peasants had developed. Luther was not talking about democracy, we were reassured; and I’m sure this was true, but now I am wondering why what the peasants thought and felt about all this never became a topic worthy of investigating.

I did, however, learn a bit about the Levellers and the Diggers in the wake of the English Civil War and, while not discouraged to think about the implications of these radical traditions, no one really encouraged me to, either. Such encouragement came well after I completed my coursework and only, like so much else I learned in my years of education, from fellow graduate students. But until reading Federici’s book last month, I have to sheepishly admit that it never occurred to me that pre-capitalist peasant revolts and heretical movements could be part of a larger struggle against both the hierarchical order of feudalism and capitalism itself which, according to Federici, in fact developed in response to the constant attempts by peasants to coerce the social structure into something far more egalitarian.[6] In other words, I had no idea that the struggle for equality reached all the way back into the feudal past. Now how, I ask, did I get a sum total of 11 years of higher education and a doctorate in history without knowing that?

I’ll pause here for a moment to recognize that this is at least in part my fault; one problem of reading (almost) every single page of your assigned reading for 11 years is that the time available to go outside of your given field and subfield is sparse, unless you really want to do nothing but read all day, every day. (And I am, unfortunately enough, a very slow reader.) Despite always having a wide range of interests, I could have made a much greater effort to learn a lot more about the Western past, not to mention the especially egregious lack of knowledge I have about everything outside of that geographical region. Nonetheless, I can’t help feeling that some knowledge was selected for omission, or at least not highlighted as relevant to understanding how we arrived at contemporary capitalism, throughout my education. This is not to point the finger at any one individual or even individuals, but to consider how the modern historical profession selects and molds what is considered relevant or worthy history, and then presents the resulting narrative as neutral, sound methodology when in fact the past is much more contested and packed with profound political implications. At least, that is what it felt like to me when Federici told me of a whole history of struggle I knew nothing of; and, moreover, told me that it could still matter.

I am sure, of course, that many scholars contest either aspects of or the entirety of her interpretations; and I am sure, moreover, that there is no easy equivalent between a peasant revolt in the sixteenth century and Occupy Wall Street in the twenty-first. That is not the argument I am pursing. But what I am suggesting is that to never be encouraged or even really offered the option to find some connections, wisdom, or contemporary relevance in the feudal and early capitalist past suggests some troubling things. There is much discussion about historians knowing more and more about less and less, and about the specious boundaries we draw between disciplines according to arbitrary lines on a map – but I think we ought to also consider the artificial boundaries we might be drawing through time, and not just through space. The past may be a foreign country, but it is not a foreign world.

[1] Quoted in Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch (Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 2004), 61.

[2] Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 10.

[3] Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 26.

[4] Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 21.

Just because it is too funny not to share, this moment occurred when, while peeing against a wall and seeing a dog doing likewise, Mather was driven to musing about the base condition of human beings. “Thought I ‘what vile and mean Things are the Children of Men in this mortal State. How much do our natural Necessities abase us, and place us in some regard on the same level with the very Dogs’…Accordingly I resolved that it should be my ordinary Practice, whenever I step to answer one or the other Necessity of Nature, to make it an Opportunity of shaping in my Mind some holy, noble, divine Thought.” Quoted in Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 153.

[6] Including, in some cases, resistance to sexual and gendered hierarchy. Who knew?! And here I thought that equality of the sexes – of any kind – was unthinkable before capitalism and liberalism.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I don’t think I’d heard of the Federici book; sounds interesting. A couple of brief notes: (1) you mention heretic and millenarian movements. Catharism was one heretical movement that definitely had different ideas about gender relations and sex than the medieval Church: see, e.g., S. O’Shea, The Perfect Heresy (2000). (2) Moving forward in time several centuries, since you start the post with a quote from Winstanley, I’ll mention Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1972; Penguin ed., 1991) — chap. 15, “Base Impudent Kisses,” deals with gender/sex.

The fifth chapter of John Donoghue’s Fire Under the Ashes explores gender, sexuality, and the Leveller movement in Coleman Street Ward. The sixth and seventh chapters reformulate the Atlantic contours of his AHR article. I enjoyed the post.

Thanks for mentioning Donoghue’s Fire. Looks like an excellent book (and one I’m sure I’d never have heard of).

I haven’t read the study by Christopher Hill.

The fourth chapter features contentions from his AHR article as well: John Donoghue, ” ‘Out of the Land of Bondage:’ The English Revolution and the Atlantic Origins of Abolition” AHR 115:4 (October 2010).

The Feb. 2003 obituary of Hill in the Guardian, which gives an informed summary of his life and work, has a paragraph toward the end about ‘The World Turned Upside Down’, noting that it’s one of the few works of history to have been turned into a play:

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2003/feb/26/guardianobituaries.obituaries

J.G.A. Pocock compared the “older Marxism” of Hill’s “Puritan creed” to Michael Walzer’s contributions in the 1975 Machiavellian Moment. An illuminating obit.

The January 2016 issue of the JHI features a *Symposium* on J.G.A. Pocock’s multivolume (I only read the two initial installments) Barbarism and Religion. I haven’t checked it out yet, though. http://jhiblog.org/