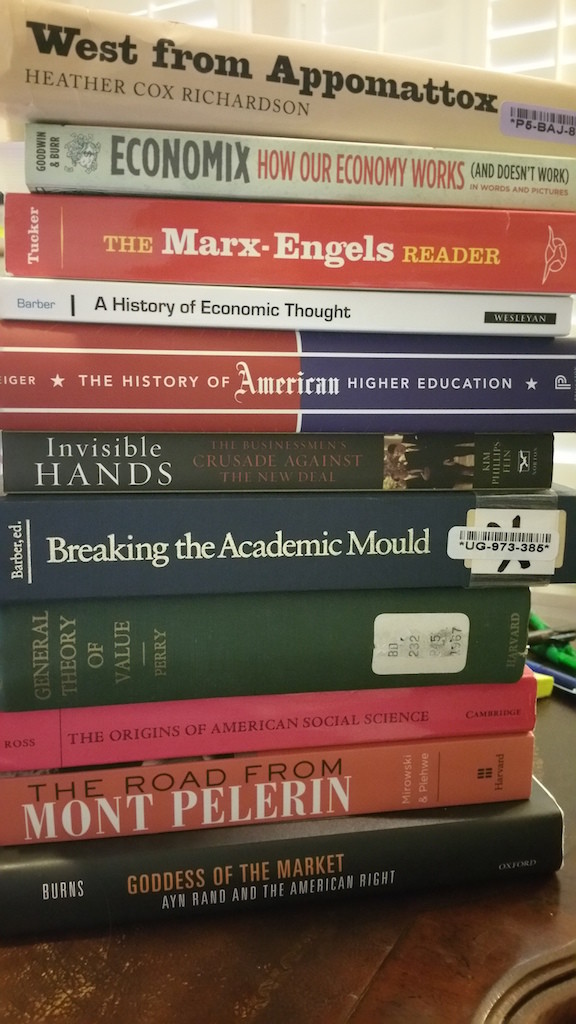

In the picture below is a stack of books that I am reading and re-reading this month. Some I haven’t started yet, some I’m in the middle of, some I’ve all but finished, some I’m reading all over again. I certainly don’t plan to review these books in this post, or even summarize them — instead, I’m going to pragmatically blurb them. That is, as the post title suggests, I’m just going to explain why I’m reading these books now and how they are helpful to me. If you have thoughts on these books, or further suggestions, or would like to share your own January reading list, please feel free to post in the comments.

West from Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America after the Civil War, Heather Cox Richardson

This book is a timely read just now for a few reasons. First, I’m putting together my syllabus for the spring semester — I’m teaching two sections of the U.S. history survey (1865 – present) and trying to figure out (as always) how to sketch a big picture (or a few big pictures) and zero in on the crucial details. The introduction to West from Appomattox is just seven pages long, and it’s a fine example of how to concisely draw in broad, bold strokes quick landscape sketch of a moment of crucial historical change. I am putting a .pdf of the intro on course reserve for my students — and I’m shamelessly plundering some of Richardson’s narrative turns and details for my own lectures on Reconstruction.

I’m also reading this book for its craftsmanship. Richardson writes with a fluid, clean, spare but not spartan prose style, well-crafted and practical, not fussy but elegant, that I greatly admire and appreciate. I couldn’t write just like her, but I just like how she writes.

Economix: How Our Economy Works (And Doesn’t Work), by Michael Goodwin; illustrated by Dan E. Burr

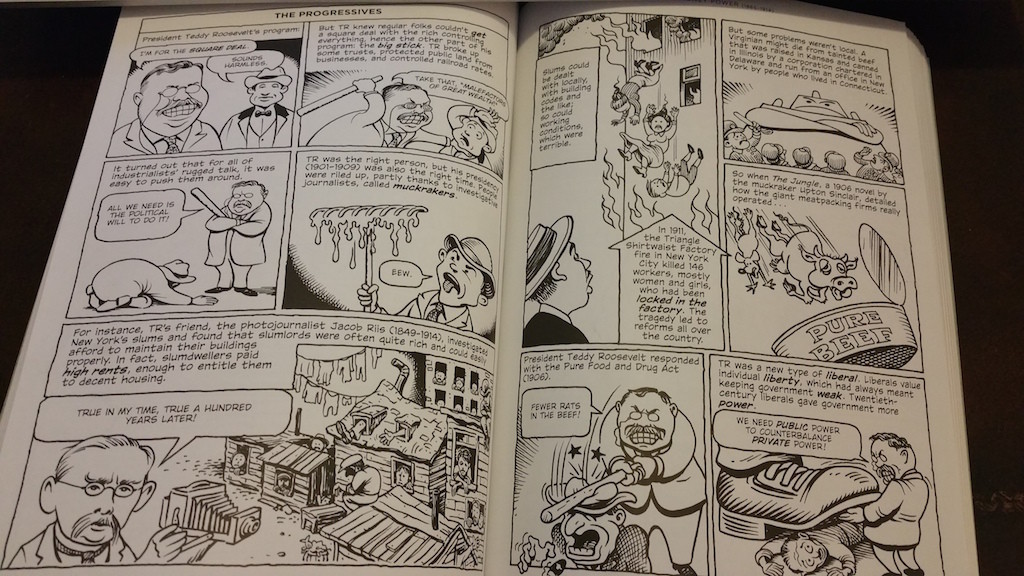

This is a really fun book for undergrads. It’s a graphic novel presenting a history of political economy from mercantilism and the Physiocrats to neoliberalism and globalization. I’m using selected pages from one of its chapters (Chapter 3, “The Money Power (1865-1914)”) to illustrate some of my lectures this semester. Here’s a sample, from the section on the Progressives.

Clearly, not a substitute for reading and discussion — but a fun visual to introduce some of TR’s domestic policy initiatives. (The slight, soft-pedaled note in the lower-right-hand corner on the shifting meanings of “liberalism” is also a nice touch, and I’ll sound that note a few times this semester.) Of course what makes this visual lively is its artful quotation of period caricatures of TR — so of course I’ll use plenty of those as well. Anyhow, this is a fun book.

The Marx-Engels Reader, second edition, edited by Robert C. Tucker

For now, I’m just reading the excerpts from Capital and the selections from the Grundrisse, for two reasons: 1) I will be leading a discussion on the Grundrisse in a new reading group that I have joined, and 2) I’m trying to carve out the boundaries of a Big Question that is lurking behind or beneath or within or around my project. I’ll explain in more detail below, but the basic problem I’m interested in is understanding changing notions of the idea of value — especially the changing historical connections (or lack thereof) between economic/pecuinary and moral/philosophical measures or judgments of value. Seems like Marx had some ideas on this.

A History of Economic Thought, by William J. Barber

This new reading group, made up of some of my fellow community college profs from history, sociology, and even philosophy, is looking this year at the history of economic thought. This brief, serviceable (albeit slightly dated) summary by William J. Barber is a good background text for all of us, useful for sketching out the contours of economic thought from Adam Smith to John Maynard Keynes. (The epilogue of the book, written for later editions, carries a note of befuddlement — Keynes’s models aren’t working; what will replace them? What indeed!)

The History of American Higher Education: Learning and Culture from the Founding to World War II, by Roger L. Geiger

I have been reading this book, off and on, a chapter or two at a time, since I defended my dissertation. After a longue-duree introductory chapter (for Americanists, that means about 100 years) on the history of Stanford University, I spilled most of my ink in that project on texts and ideas swirling about from the 1960s to the 1990s. I missed being able to think about the “backstory” of the university in American cultural history — the broader view, the longer view. But I would never have been able to think about that longer story with the clarity and command of Geiger, who has been thinking deeply about that broader view for a long time. This is a very fine, richly sourced synthesis of the history of higher education in America. And as prose style goes, Geiger’s is also a pleasure to read. His writing too shows an elegance, economy and balance that I especially appreciate at present, as I try to regain my own sense equilibrium as a writer.

Invisible Hands: The Businessmen’s Crusade Against the New Deal, by Kim Phillips-Fein

The Road from Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, edited by Philip Mirowski & Dieter Plehwe

Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, by Jennifer Burns

I’m grouping these three books together (perhaps over the objections of Mirowski & Plehwe, who were a little testy in their new preface regarding the work of both Burns and Angus Burgin) because I’m still working out whether and to what extent I can make a truly defensible claim that the ballyhooing of “the market” that I’m seeing in particular primary sources from the 1960s is actually neoliberal thought; perhaps my sources just reflect earlier valorizations of the market as the arbiter of (some? all?) values. I have gone out on a limb with my argument — this is neoliberalism! in the 1960s! — and I’m looking to these three texts (plus Burgin and Stedman-Jones) to figure out if I really want to be that far out there.

Breaking the Academic Mould: Economists and American Higher Learning in the Nineteenth Century, edited by William J. Barber

The Origins of American Social Science, by Dorothy Ross

I bought the Barber collection for its essays on the founding and early culture of the economics departments at Stanford, Berkeley, and the University of Chicago, and I have read both of those chapters. (“Political Economy in an Atmosphere of Academic Entrepreneurship: The University of Chicago,” by William J. Barber; “Political Economy in the Far West: The University of California and Stanford University,” by Mary E. Cookingham) I will probably get around to the other chapters, but for now I’m focused pretty tightly on these departments and institutional cultures.

I’m collating this sort of reading within Dorothy Ross’s larger overview of the ideas animating the emergence of the social sciences as modern academic/professional disciplines. (In fact, I think Ross cites one or another of the essays from the Barber collection in Origins of Social Science.) And I’m coming back to Ross again for an idiosyncratic reason: I’m trying to get a bead on Clark Kerr. Bringing the full force and power of Ross’s intimidatingly thorough analysis to bear on this very small and very simple question — “So where was Clark Kerr really coming from?” — is a little bit like using a bazooka to kill a gnat. But, by golly, I bet I hit that gnat.

General Theory of Value: Its Meaning and Basic Principles Construed in Terms of Interest, by Ralph Barton Perry

The reason I’m reading this book — or will be reading it; haven’t started it yet — is right there in the title: I’m interested in theories of value, and curious about Perry’s formulation of a theory of value that (as I understand it from others’ summaries) encompasses (in fine Pragmatic fashion?) the economic and the moral, the pecuniary and the philosophical, all framed (so it seems from the table of contents) in terms of functional psychology. This book may end up moving to my “February list” — it’s not going to be a quick or easy read. In any case, it does represent an example of an explicitly articulated set of ideas, from the early 20th century, related to the Big Question I am grappling with these days.

Okay, that’s my list. What are you all reading?

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’m reading (slowly/desultorily) Sperber’s Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life. Have also recently bought R. Vitalis, White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations (partly b.c. the publisher, a univ. press, had a sale in December).

After you finish w the Marx excerpts, you might (emphasis on “might) be interested in R.P. Wolff, Moneybags Must Be So Lucky: On the Literary Structure of ‘Capital’. Haven’t read it but have read a bit of the author’s other stuff (including, from time to time though not recently, his blog). From occasional glances at his blog etc., I’ve been reminded of Capital’s literary/metaphorical dimension, as e.g. when Marx in Vol. 1 ch. 3 describes prices as “wooing glances cast at money by commodities.”

I’ve got that Geiger book on my bedside table but haven’t started reading it yet. You’ve inspired me to get going! I would love to hear your thoughts on it vis-a-vis, say, Hofstadter + Metzger’s classic work or anybody else working in that vein (Veysey, Reuben, Thelin).

Barbara Hernstein Smith’s _Contingencies of Value_ (1988) may prove helpful to your inquiry into the history of value–it’s a survey and critique of the topic of evaluation, slanted towards her interests in literature and philosophy. And it was written in part during the hey-dey of the culture wars–so, a double-whammy for you! The last chapter of John Guillory’s _Cultural Capital_ is quite dense but links Adam Smith’s ideas of value to questions of literary value.

Patrick, thanks so much. I looked at both Herrnstein-Smith (who was referenced repeatedly in one of my key primary sources) and Guillory, who was one of my theoretical guideposts — and they are both in their way very much of that “Culture Wars” moment (though I don’t really use that periodization). I guess what I’m trying to do is trace out historically the ideational path(s) that got them there.

Herrnstein-Smith, BTW, is another wonderful writer. For someone who was categorized by some as a spokesperson for Theory, she has produced some pretty limpid prose.

Louis, thanks for sharing your reading list. I am not in a spot where I can look at a biography of Marx (unless this one is an intellectual history disguised as biography — those are the best!), but I’ll add it to my (at this point increasingly aspirational) queue.

I’ve gotten some great reading suggestions on the USIH Facebook page and on my own page (in addition to Patrick’s input, above), so those go in the hopper as well.

Over at my own blog I have a little more to say (in a way, I guess) about how/why it is that I am sort of reading all these books at the same time. (Quick and dirty: think the flood scene in “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” — except George Clooney is nowhere in sight.)

Anyway, as the Good Book says, Of making many books there is no end — nor of reading them either. For which I say, Hallelujah! Amen!

Not knowing what you’ve read (or not read) to date regarding “value,” I’ll simply share some titles that I’ve found helpful. On the notion of value in general, Robert Nozick’s Philosophical Explanations (Harvard University Press, 1981) is indispensable, as is Elizabeth Anderson’s well-known and highly praised Value in Ethics and Economics (Harvard University Press, 1993). And of course Nicholas Rescher is another philosopher who has written much on value from a “pragmatic” perspective that should be required reading. After these, and in no particular order, there is Michael J. Zimmerman’s The Nature of Intrinsic Value (Rowman and Littlefield, 2001), Michael Stocker’s Plural and Conflicting Values (Clarendon Press, 1990), and Joel Kupperman’s Value…And What Follows (Oxford University Press, 1999). On the role of emotions with regard to judgments of value, Martha Nussbaum’s Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions (Cambridge University Press, 2001) articulates a nice argument of behalf of a (‘neo-Stoic’) cognitive approach.

As for Marx’s theory of value and the forms it assumes in exchange relations, and in addition to the usual suspects, the little volume edited by Diane Elson, Value: The Representation of Labour in Capitalism (Verso, 2015, originally published in 1979) is very good.

(As for what I’m reading, I doubt strongly anyone is interested enough for me to take the trouble to compile a list.)

Patrick O’D., you’re a gem. As to whether or not anyone is interested in what you’re reading — try me.

Regarding the whole matter of what’s interesting — and “interesting” is an, uh, interesting word that is used to stand for scholarly value(s) (I guess I should see Ralph Barton Perry on this) — I will return to my observation on the FB group page. If someone had told me five or six years ago that I’d be plunging into the history of economic thought, on purpose, I would have laughed him or her out of the room. I really did almost title the post, “What am I reading, and why?”, because this is not a list I would have come up with in 2010, never mind before then.

But that title wouldn’t be fair to the titles on the list. I won’t claim that these books are intrinsically interesting and would command anybody’s attention, but they’re valuable to many kinds of readers beyond yours truly.

Looking at the stack again, I think it’s fitting that it’s bookended, as it were, with the titles by Richardson and Burns. One of the “interests” behind choosing this particular set of books now, and not others — and an interest I didn’t really even recognize at first as a unifying thread — is to read well-crafted scholarly works of narrative history. We talk a lot on this blog about narrative — whether it’s pernicious or not, whether it’s clarifying or not, whether story perhaps always manages to corrupt or divert analysis. (Or, we take all that as a given, and we talk about whether we should still make any room for narrative.)

Anyway, in my own writing, I have struggled a lot with managing the tensions between narrative and analysis, and the muddy trackmarks are all over my project in its current state. My surmise is that Richardson and Burns (and Geiger and Phillips-Fein and Ross as well) struggled with some of the same tensions. But somewhere between the first draft and the final version, they sure figured it out. And it’s so nice and refreshing and encouraging and inspiring to read such clean, clear, deft historical narrative. No mud, no track-marks. Reading these works is a way to recalibrate my historian brain for the next round of effort.

Anyway, thanks as always for the titles. But, seriously, what are you reading this month?

OK, in response to your gracious request, here is a partial of list of books I’ve recently read (over the break, which has yet to end), am reading afresh, or plan to read soon. I’ve left out works related to Islamic Studies and those associated with my latest bibliography, “The Black Struggle for Civil Rights, Freedom, & Equality in the U.S.” (I always try to read a fair number of works in the subject matter of these compilations, both by way of preparation and to get in the spirit, so to speak, of the bibliography).

• Graham, Keith. Practical Reasoning in a Social World: How we act together (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

• Hollis, Martin. Reason in Action: Essays in the philosophy of social science (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

• Kincaid, Harold. Philosophical Foundations of the Social Sciences: Analyzing Controversies in Social Research (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

• Miller, Richard. Fact and Method: Explanation, Confirmation and Reality in the Natural and Social Sciences (Princeton University Press, 1987).

In conjunction with a forthcoming book review: Hélène Landemore’s Democratic Reason: Collective Intelligence and the Rule of the Many (Princeton University Press, 2013); several books each by Gerald Gaus, Robert E. Goodin, and Adam Przeworski, Gerry Mackie’s Defending Democracy (Cambridge University Press, 2003), a definitive analytical and empirical refutation of Arrow’s impossibility theorem for social choice theory; Nadia Urbinati’s Mill on Democracy: From the Athenian Polis to Representative Government (University of Chicago Press, 2002), Representative Democracy: Principles and Genealogy (University of Chicago Press, 2006), and Democracy Disfigured: Opinion, Truth, and the People (Harvard University Press, 2014); S.A. [Sharon] Lloyd’s Ideals as Interests in Hobbes’s Leviathan: The Power of Mind over Matter (Cambridge University Press, 1992), and Morality and the Philosophy of Thomas: Cases in the Law of Nature (Cambridge University Press, 2009). If you’ve not read Lloyd’s books, I’ll dare to claim that it is highly probable that your understanding of Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy is deeply mistaken. I would include these two books among the best works in political philosophy I’ve read in my lifetime.

And the remainder, in no particular order other than the way in which they’re placed in piles around me:

• Kincaid, Harold and Jacqueline A. Sullivan, eds. Classifying Psychopathology: Mental Kinds and Natural Kinds (MIT Press, 2014).

• Adams, Vincanne. Doctors for Democracy: Health Professionals in the Nepal Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

• Adams, Vincanne, Mona Schrempf, and Sienna R. Craig, eds. Medicine between Science and Religion: Explorations on Tibetan Grounds (Berghahn Books, 2011).

• Lepora, Chiara and Robert E. Goodin. On Complicity and Compromise (Oxford University Press, 2013).

• Gana, Nouri, ed. The Making of the Tunisian Revolution: Contexts, Architects, Prospects (Edinburgh University Press, 2013).

• Martin, Daniel. On the Corner: African American Intellectuals and the Urban Crisis (Harvard University Press, 2013).

• Burston, Daniel and Roger Frie. Psychotherapy as a Human Science (Dusquene University Press, 2006).

• Brakel, Linda A.W. Unconscious Knowing and Other Essays in Psycho-Philosophical Analysis (Oxford University Press, 2010).

• Brakel, Linda A.W., ed. Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and the A-rational Mind (Oxford University Press, 2009).

• Coady, C.A.J. Messy Morality: The Challenge of Politics (Oxford University Press, 2008).

• Krausz, Tamás. Reconstructing Lenin: An Intellectual Biography (Monthly Review Press, 2015).

The second Lloyd title above should read: Morality in the Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes: Cases in the Law of Nature (2009).

Lord have mercy. Good luck on your comps!

😉

I don’t read anywhere near as much as Patrick S. O’Donnell, but it so happens I have read (part of, and a long time ago) one of the books he lists above: Richard Miller, Fact and Method. It struck me as a pretty careful, balanced, well-written, insightful book by a philosopher prob. trained in the analytic mode but with wide interests; at the same time, I found the parts of it I read to be somewhat dry. Basically, it’s not much fun, the way some books even on difficult subjects can be. I would not recommend it to anyone except someone with a fairly hard-core interest in the philosophy of science (incl. the philosophy of the social sciences). I don’t believe I still possess the paperback copy I once had; I think I gave it away. I also don’t remember much of the argument except that he comes down sort of on

‘the natural and social sciences are indeed different in methods and standards of proof etc., but not quite as different some people have argued’. If that’s wrong, I’m sure Patrick O’D., having read the book more recently, will correct me.

correction:

as some people have argued

I also appreciate Patrick O’D’s list for bringing to my attention certain bks I really have no desire to read. For ex., I doubt the proverbial wild horses could drag me to read Landemore’s Democratic Reason, for reasons not worth going into. (Of course, if someone asked me to review it, which no one would, that might be a different story.)

Miller’s book is invaluable for a critique of recalcitrant positivist and post-positivist methods in both the natural and social sciences without succumbing, in the latter case, to hermeneutic or narrative or phenomenological approaches to topics that warrant scientific examination and explanation. It also contains a wide ranging treatment of causation, a small taste of which I provide here: http://www.religiousleftlaw.com/2015/12/the-capabilities-approach-to-health-and-social-justice-moving-from-the-individualbio-medical-or-natu.html The book by Kincaid is more along the lines that methods, etc. are not that very different between the natural and social sciences, providing several excellent in-depth examples by way of demonstrating precisely how the latter that can meet the causal strictures and explanatory standards set by the former. I provide just a taste, yet again, of Kincaid’s book in this post: http://aglaw.blogspot.com/2015/12/agrarian-revolution-marxist-sociology.html

As for Landemore’s book, it is very well-written and, I think, a landmark work in democratic theory, providing a compelling portrait of “democratic reason” and a basic outline of what a full-fledged (i.e., not just procedural) epistemic justification for democracy should and can look like, one based on relatively recent and persuasive research on distributive and collective intelligence. By my lights, she is one of our foremost theorists in democratic theory (along with Nadia Urbinati and Robert Goodin).

Miller’s book is invaluable for a critique of recalcitrant positivist and post-positivist methods in both the natural and social sciences without succumbing, in the latter case, to hermeneutic or narrative or phenomenological approaches to topics that warrant scientific examination and explanation.

Which kind of amounts to saying he steers a sort of (sophisticated) ‘middle course’, no? which is sort of what I remember. Anyway, thank you for the links to your posts for the fuller discussions.

p.s. Also interested to learn of the existence of the Agricultual Law blog; had no idea the AALS had a section on agriculture and food law.

p.p.s. Your select biblio on philosophy of the social sciences is v. good, so thks for that also.