Shorter story of my life: I never realize what I have in my hands until it’s too late.

For my chapter on the history of undergraduate education at Stanford from 1891 to 1970, I managed to snag my own copy of a key primary source: the ten-volume Study of Education at Stanford (1968-69). As you can see from the photo, these are not thick tomes – they are slim octavo volumes, with the longest (Vol. VIII – Teaching, Research, & the Faculty) clocking in at a light 144 pages.

In fact, the whole reason I bought this set was to read Volume VIII. This volume features personal essays and signed memos by several Stanford faculty members who responded to the SES committee’s queries about their experiences teaching undergraduates at Stanford. Many professors wrote frankly and at length about how their teaching fit in (or didn’t) with their research and writing. (Quick and dirty summary: even at Stanford, it was never all wine and roses. Plus ça change…)

As it turns out, I didn’t use that volume at all in my chapter. My research took me in another direction, so I ended up focusing mostly on the first two volumes in the Study.

Here they are:

As you can see, someone has written an acronym on the cover of each of these volumes: RWL. When I saw the inscription, I wondered what it stood for – my best guess was something like “Reading and Writing Lab” – but I didn’t spend much time thinking about it. I was much more interested in the contents of these two volumes, focused as they were upon making a case about the need for a change to undergraduate education at Stanford and then spelling out what those changes should be. On a few pages of Volume 2, someone in the “RWL” office had written a few notes in the margins, questioning the logic of the report at various points, and suggesting alternative conclusions.

Occasional marginal comments and front-cover inscriptions aside, though, all ten of the volumes in this set were in very good condition. So I used them as I needed to for that chapter, and then I set them aside and turned my attention to other chapters and other problems.

When I was formatting the final copy of my dissertation for submission to my whole committee, I wanted to double-check how to cite selected volumes from a multi-volume series and make sure I had done that correctly. Since the SES was published over a number of years, I wanted to make sure that I included the right year(s) in both the footnotes and the bibliography. So I grabbed the whole set from my bookshelf, set it down in one stack on the right-hand side of my desk, and started to go through the set one volume at a time, checking the date on each copyright page. When I was done with a volume, I flipped it upside down and set it aside to my left.

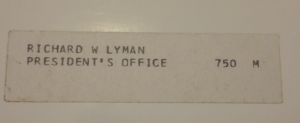

When I flipped over the fifth volume in the series, I saw the label on the back

:

Ah. So that’s what “RWL” stands for. That would have been good to know when I was writing the chapter about the curricular changes of the 1970s, that pivotal decade during which Richard W. Lyman, who had been the Provost during the most tumultuous years of campus protests at Stanford, served as the President of the University and signed off on the effort to revive a Western-Civ-type requirement. Sigh.

But at least I know it now.* So while I didn’t draw from Lyman’s private (and occasionally rather pointed) notes on the committee report for my dissertation, I will certainly look more closely at this and related material while I’m working on the book. For sometimes the smallest bit of evidence, carefully interpreted and contextualized, can yield the biggest insights.

New moral of the story, politely-worded version: It’s never too late; that’s what revisions are for.

New moral of the story, inner-monologue version: FFS, LDB, you’re the one who’s always going on about the materiality of texts, how people need to pay attention to the form in which ideas are expressed, yada yada yada — so pay attention already!

____

*I’m no paleographer, but the handwriting in the marginalia seems to me to match the handwriting on my copies of materials from Special Collections that Lyman annotated and signed. But of course I won’t make any claims I can’t be sure of.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

It’s never too late to go in for material texts and history of reading. Happy new year!

Ha! Thanks — I’ll do my best. Happy New Year to you too!

What a great find! …On your opening epigram, well, it happens to all of us. Sometimes in our historical work, especially at the publication stage, you know exactly what you have and you have to exclude it anyway. Sigh. – TL

Thanks Tim. I laughed ’til I darn near cried when I saw that label. I mean, I used Lyman’s own book about his years at Stanford, in the very same chapter — the very same section, in fact — in which I discussed this report. You can look at something and look at something and just not see it. (This is why historical scholarship generally takes a long time and pretty much assumes a re-vision of issues and interpretations and sources already “settled.”)

That said, I really should have seen this — if not via an epiphany, then via noticing the damn mail room routing labels stuck on the back of a few of these volumes — before I was triple-checking the format of my footnotes.

For much of my larger argument, I made a great deal out of the materiality of the codex — and I intend to make a great deal more of it as I move forward. (As I wrote on my own blog, I did unearth my receipt from this purchase, and went back to the same used bookstore to buy a couple more higher ed titles that had belonged to Lyman and that, per the item descriptions, contained several pages of his notes.) But this material girl missed the rich resource that was sitting right in front of her!