Last week I talked about my agreement with Andrew Hartman that a) the culture wars are effectively over and b) the conclusion to his book is very depressing. However, I decided to leave out noting the one aspect of criticism of his thesis that I do find compelling, and that is the role of race in the culture wars.

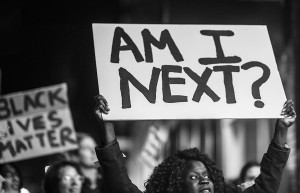

As Jacqui Shine pointed out in her review, the last year or two (and really, one could argue the last 7 years, ever since Obama got elected) can hardly be described as racially harmonious. Of course, no such status has ever been reached in American history, but the rise of Black Lives Matter and the capacity of video evidence to spark wide spread protest has brought the problem of racism to the forefront of the nation’s attention to an extent that has not been seen in decades. So where, then, does this reality fit into the idea that the culture wars are somehow “over”?

Asking this question requires us to interrogate what analytical concepts are most useful in understanding the function and functioning of white supremacy. Is racism a part of American culture? Very much so yes, clearly. Yet we rarely describe racism as merely an issue of “culture,” especially when our particular national version of it developed in the context of struggles over power and resources in colonial America. Yet of course, even in that creation, cultural norms were invoked and employed to help build what came to be American slavery. Power struggles never take place independent of, or outside of, culture.

Obviously I am circling around multiple epistemological problems here, from the chicken and egg question to “what is culture, exactly?” and equally obvious the answers are something like “it’s all tied up together” or “our convenient categories are exactly that, merely convenient.” I’m hardly going to untie that big knot right now, not the least because I end up as confused as anyone when trying to pull it straight. But I do want to hazard a few thoughts as to why race in America is particularly good at drawing us into these problems.

In A War for the Soul of America, Andrew gives us a rich analysis of the discussion among academics and public intellectuals (categories that do not always overlap) about race. For example, when discussing the debate over affirmative action, he concludes that “[the] line that divided opponents in the affirmative action debate, then, was the line between an older colorblind racial liberalism and a newer color-conscious racial liberalism that had incorporated elements of Black Power into its theoretical framework.”[1] Critical Race theorists, in particular, recognized the limitations of colorblind ideology and how it operates to actually perpetuate racial inequalities. Conservative intellectuals, meanwhile, made principled appeals to meritocracy and individualism. More unusually, they tried to resurrect the respectability of scientific racism, as Charles Murray did in The Bell Curve – this however, was fairly rare (although Murray was defended by nearly all conservatives, a telling fact in and of itself), and most stuck to colorblind arguments that would have been almost solely the domain of liberals a few decades before.

Yet discussed much less are the views and perspectives of the majority of white people in the country. There is, in a way, a good reason for this – as far as fully articulated, something-approaching-coherent arguments go, there wasn’t much of a debate amongst white Americans. As the 1960s receded further and further into the past, as Andrew notes, “beyond academia, color-consciousness was becoming increasingly unacceptable in the national political realm.”[2] Political leaders made this move, moreover, not out of their own initiative but because of an electorate opposed to further efforts to rectify racial injustice. Nixon, for example, began as a reluctant advocate of affirmative action but “[a]lways attuned to white majority opinion, [he] reversed his tepid support for affirmative action.”[3]

Conservative spokespeople (so to speak), took this white-majority aversion to color-consciousness and translated it into colorblind ideology – not necessarily because every “racially conservative” American deeply believed in her heart and soul in colorblind liberalism, but because racism simply was not publicly acceptable anymore. Exactly how that happened is actually a much more fascinating question than we historians, who think we at least know the answer to this question!, might assume – if you want to tread down that road, I would suggest this Crooked Timber post from a few years back. But regardless, one of the most basic ideas of Critical Race theory is that colorblind liberalism grew in popularity precisely because it could, ironically enough, be used to perpetuate white supremacy.

So here’s my question: if this is the case, why, then, do we tend to analyze and argue with “colorblind conservatives” on their own terms? More bluntly – why do we take them so seriously? I’m not claiming that Andrew is a particularly enthusiastic participant in this – at several points he is not sparing in his analysis of their work – but he does, however, inherent a bit of a tradition of taking them at their word, which makes this whole issue of how race fits into the culture wars particularly muddy. Take, for example, the use, in one of the most celebrated books on the politics of race, of the term “racial conservatives.” What, exactly, distinguishes a racial conservative from a racist or, to avoid to the unfortunate tendency to personalize all power relations, someone who participates in racism quite a lot? Is there one? If not, why can’t we just call these folks racists or, advocates of white supremacy? After all, as Andrew notes, “[w]hat the politics of welfare demonstrated was that powerful counterrevolutionary forces were bent on preserving the color line, in substance if not in style.”[4]

The first obvious answer is that we cannot do this because this is not how they understand themselves, and if we refuse to engage with them on their own terms, no forward discussion is possible. I certainly have my own huge can of worms to say about that, but putting that aside let’s just say, theoretically at least, we’re just having a discussion amongst ourselves (us being color-conscious liberals and leftists). How much sense does such ambiguous terminology really make? Some reviewers of Andrew’s book pointed out that things looking an awful lot like the culture wars – such as the 1920s – occurred in America well before the sixties. So let’s imagine if we referred to the resurgent KKK of that time period as an organization of “racial conservatives.” This would likely be considered absurd, but is there any real debate (amongst the left broadly construed, that is) that the pundits and politicians who fear-monger about Obama on a daily basis are inheritors of the same tradition?

If so, how do we conceptualize the issue of race in the culture wars? I absolutely agree with Andrew that the culture wars were something special, a particular response to a decade of particularly rapid and intense social change and conflict. But from the perspective of the entire sweep of American history, they also appear as just one distinct chapter in the longer story of American racism. A similar argument could be made about gender – the Religious Right prefers to frame their views on marriage as consisting of “family values,” but as the mainstream gay marriage movement repeatedly pointed out to great effect, such “values” actually consisted of a dogged defense of heteronormative patriarchy. Of course this a cultural value, but so are meritocracy and individualism – but is it possible to really separate the valuing of meritocracy from the valuing of elitism, or the valuing of individualism from the history of white supremacy? In other words what, exactly, are we talking about when we talk about the culture wars?

Although this post is full of rhetorical questions, that last one is for real – I’ve thought through this post several times and I always end up at the edge of what feels like a rabbit hole. So, where to from here? Should we apply Occam’s razor to this quandary, or is the only way out to go ahead and fall in?

[1] Andrew Hartman, A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars, (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), 105.

[2] Hartman, A War for the Soul of America, 112.

[3] Hartman, A War for the Soul of America, 106.

[4] Hartman, A War for the Soul of America, 120.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is great, a nice reminder of how the construction of race cannot be separated from cultural formations. But we shouldn’t forget that racism is not exclusive to conservative circles, it is also pervasive in so-called liberal and even radical leftist white spaces. The forms that racism adopts in such spaces are more subtle than the discourse of a Charles Murray, but it still rears its ugly head in different ways, as one could witness in the backlash against the Black Lives Matter intervention in the Bernie Sanders rally in Seattle back in August, or the loaded discussions about black activism in college campuses, or hell, in the laughter provoked by Quentin Tarantino’s use of the n-word for comical effect in his movies.

There’s a lot going on in this post, Robin Marie. I am very appreciative of your deep engagement with my book, particularly my chapter on race which has not been the subject of many reviews. Let me respond to what amounts to a series of smart rhetorical questions that you posed with a rhetorical question of my own: what benefit is there in an historian naming something “racist”? As I make clear in my book–and as you make clear in this post–colorblindness, whether liberal or conservative, had the effect of narrowing or limiting potential civil rights gains. So yes the effect can be called racist, and perhaps that was the intent of some if not all of the major players involved. But calling them racists does what exactly? It’s a serious question.

Someone asked me why I use the term “homophobe” to describe anti-gay rights activists in the book. They thought that eventually, as the issue of gay rights becomes more settled and less emotional or present, such judgmental language will become less common in historical scholarship. Perhaps she is right, but I don’t know. So what do you think?

Thank you both for these great comments!

@Kahil – I agree completely. And the ubiquitous nature of racism is, I think, another reason why it is harder to fit race into a culture wars frame; not only are very few people now openly advocating white supremacy, but most people would be shocked to discover their own participation or complicity in it.

The lines cannot be so clearly drawn not only because we don’t acknowledge them, but because they are rather fuzzy and porous indeed.

@Andrew – Thanks so much for posing that question so clearly. You are right, it is a very serious one, and I think about it a lot. My answer is, to put it simply, akin to a war of position argument. I know the academy has very limited power to impact public discourse, but precisely because the left is so small and culturally weak, it seems really important to me that as many people as possible are encouraged to, so to speak, keep it real. The more people who refuse to use polite, coded, or compromised language when discussing the realities of power in the country, the more, I hope, the politics of resisting and refusing those realities becomes thinkable. I don’t know this, obviously, but I do hope.

I actually disagree with your colleague; I think as time passes, it will be easier to use judgmental language, and maybe even something more harsh than homophobe. You see the term “negrophobe” sometimes in mid-century writing; almost no one uses it now (or its correlate, “blackphobia”), because as something becomes disreputable its origin is more likely to be associated with hate or power than fear, I think. I mean no one refers to Nazis as “Semitephobes,” and people are pretty comfortable calling folks like George Wallace bigots. The further a sin recedes into the past, the less implicated we feel in it; but while there is more of a real debate about whether or not something is wrong, we implicate ourselves or, even just feel uncomfortable as we probably implicate friends and family we care about with such damning language. No one likes to think of their loved ones as racist or bigoted or what have you.

Another factor important to me is one of solidarity – what would most people subject to racist ideas call racist ideas? Most of them that I know personally call them racist, and their practitioners racist. Now if I disagreed that would be one thing. But I do not, and moreover, I’ve seen how withholding from using these terms, for reasons of professionalism, politeness, or just to avoid conflict, marginalizes them and reinforces the whiteness of, in particular, the academy. I think, really, having personal friends (one who eventually left the academy because she eventually got sick of such constant micro aggressions going unacknowledged) who deal with that kind of thing day in and day out has really impacted my feelings on an issue like this. My solidarity is not only political, in other words, but personal; and we know I don’t draw too sharp of a distinction between those two things, anyway.

Robin Marie’s questions are complicated enough when they apply to people who are selfconscious about “intellectual history.” What I would like to see is some application of those questions to people who are educated and who manage or run schools of engineering, schools of medicine, police departments, profit-making businesses, and so on. They have to make decisions every day that assume “race,” even when it is necessary to convince themselves that “race has nothing to do with it.”