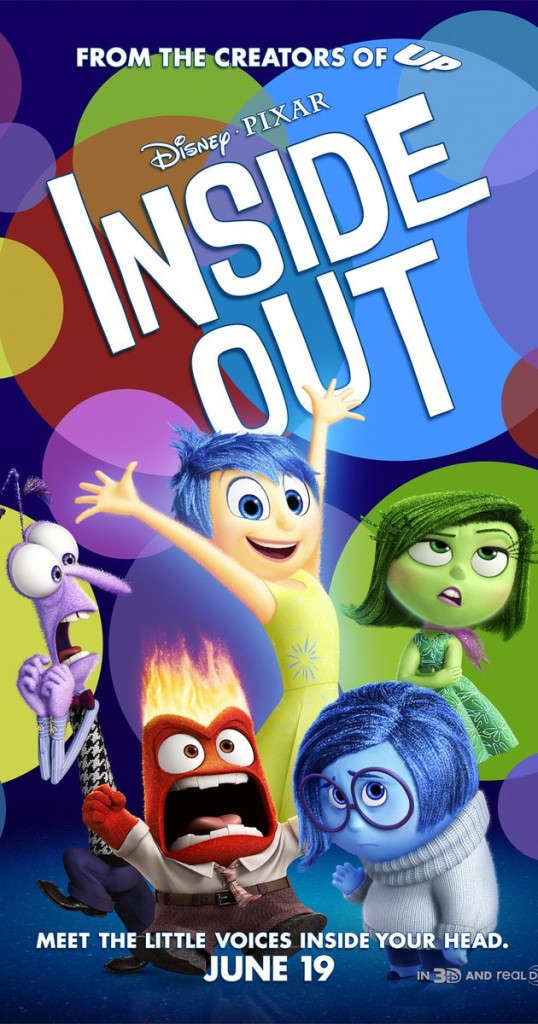

Last night was family movie night, and the selection was Inside Out. This is the Disney-Pixar film that takes place inside the brain of an 11-year-old girl. There, five characters – Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust – “see” out through the girl’s eyes and negotiate her responses to the challenges of her world at a control panel with buttons and levers. We saw the film when it came out in the theaters and were watching it again on DVD, at the urging of my eldest, also an 11-year-old girl. The film is brilliant and moving, but as I watched, I began to wonder whether she and her brother would see the logical problem of its central conceit. The protagonist, after all, is not the girl but the emotion, Joy. Like the girl does, Joy has a body. Like the girl, Joy displays a range of emotional responses as she confronts a series of challenges in her world. Does that mean Joy also has a set of five characters inside her head standing before their own control panel? And do each of them have sets of characters at control panels inside their own heads?

Joy and her colleagues are examples of homunculi, little creature-like beings inside human beings that help us explain difficult things like intention, conscious behaviors, and other end-directed activities. As Terrence Deacon, the neuro-anthropologist and professor of cognitive science at UC-Berkeley explained in his book, Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter (2012), homunculi were what early naturalists imagined to be inside spermatozoa. Although science long ago rejected homunculi of this type, they still mark, Deacon argues, “an explanatory hole” found in many of our accounts of reality (22). This is true not only for obvious aesthetic accounts like those of Inside Out but for scientific ones, too, where the homunculi tend to be subtle and well-hidden. In the same way that Joy operates at the interface between an 11-year-old-girl’s mind and body, scientific homunculi continue to hide the lack of connection between mentality and materiality in our most authoritative accounts of how things work and what’s real.

Joy and her colleagues are examples of homunculi, little creature-like beings inside human beings that help us explain difficult things like intention, conscious behaviors, and other end-directed activities. As Terrence Deacon, the neuro-anthropologist and professor of cognitive science at UC-Berkeley explained in his book, Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter (2012), homunculi were what early naturalists imagined to be inside spermatozoa. Although science long ago rejected homunculi of this type, they still mark, Deacon argues, “an explanatory hole” found in many of our accounts of reality (22). This is true not only for obvious aesthetic accounts like those of Inside Out but for scientific ones, too, where the homunculi tend to be subtle and well-hidden. In the same way that Joy operates at the interface between an 11-year-old-girl’s mind and body, scientific homunculi continue to hide the lack of connection between mentality and materiality in our most authoritative accounts of how things work and what’s real.

The theory of natural selection, for example, hides its own homunculi. Why are organisms striving to adapt, to organize themselves within their environments? Why, it’s because there’s a tiny creature at a control panel inside them pushing the “adapt” button, pulling the lever marked “survive.” “Function” is another common placeholder for mind-stuff, covering the explanatory hole where, in our official accounting of reality, mind and matter fail to connect.

Although Deacon is not the first to do so, he presses anew the argument that this failure to connect makes for a fundamental incoherence in modern thought. Having failed to achieve any “balanced resolution” to the ancient mind-matter problem, modern science bracketed it, explained it away with various homunculi, so that scientists might get on with their work of understanding and gaining control of the material world. Most humanities scholars, too, I would think, go about their tasks with a similar working dualism, as if this incoherence could be safely ignored. There’s a certain lag going on here. The New Physics of the early twentieth century refuted much of Newtonian physics, and since then several varieties of postmodernism in science have continued to ‘de-materialize matter,’ so to speak, and ascribe to it mental attributes. Yet when it comes to the way most of us organize perception — scientists and non-scientists alike — we are still living, Deacon claims, “in the shadow of Descartes” (6).

Is it safely ignorable? Can’t we continue on as we’ve been going, dividing up the magisteria, granting that related to the empirical to science, granting that related to mind to the humanities (and letting the social sciences scramble for a place in between)? That might be tenable, were both magisteria given even a roughly equal status. But they aren’t, as we all well know. As the centuries since Descartes passed, framing explanations for how the world works increasingly privileged the material and rested on a physics of energy and force. All goings-on, no matter how complex, were thought to be reducible to mindless interactions at the microscopic level. The causal efficacy of mental content was dismissed as a matter of principle. In mainstream science, this is all still mostly the case, just as it still undergirds the way ‘thoughtful people’ organize their perception in society at large. Yet life itself – at least the experience of it – continues to be permeated with the stuff of mind. Deacon provides a useful list: the what-might-be, the what-could-have-been, the what-it-feels-like, the what-it-is-good-for, and the represented-by-something-else. This stuff is ubiquitous and commonplace, yet how is it to be explained? Is it sufficient to see it as a mere rhetorical stand-in for physical events yet to be explained?

Deacon doesn’t think so. The fundamental incoherence, the explanatory hole in our working dualism, where some homunculi always “waits at the door,” is, he claims, “the central problem of contemporary science and philosophy” (58). In Incomplete Nature, he aims to re-naturalize end-directedness, representation, and other mindstuff, to re-legitimize it with a precise and non-mystical account. He describes a dynamic process in which ordering tendencies work to produce novel forms that marshal energy to constrain, in ever more complex ways, the disordering tendencies that lead to entropy. Life, in other words, is a sort of constant end-run around the second law of thermodynamics.

As his subtitle, “How Mind Emerged from Matter,” suggests, he leans heavily on a body of thought in the postmodern life sciences known as emergence theory. He surveys this thought and offers a version of his own. Deacon’s model takes the form of a tri-fold hierarchy. Thermodynamic processes give rise to morpho-dynamics, processes whose constraints create and recreate form. When forms created by morpho-dynamics become so complex that they are able to set out their own “boundary conditions” and contain their own “constraints,” a third level of dynamics emerges. Deacon calls this teleo-dynamics. Now end-directed processes become part of the system. Now the system has the attributes of mind.

Obviously, the above paragraphs don’t begin to do justice to Deacon’s patiently detailed argument. I think the crucial point, though, is this hierarchical emergence. It speaks to the question of reducibility. When mind-stuff is reduced to physical stuff, its status is deflated. The epiphenomena is inferior to the phenomena. With each emergence into a higher level, as Deacon has it, a threshold is crossed and a new dynamic is realized. Non-physical phenomena emerge from a wholly material substrate, but the nature of the threshold is that these non-physical characteristics cannot be reduced to the lower processes. Between each a causal phase change, a kind of firewall over which no accusations of unreality or irrelevance can be lofted. Others who have waded into these depths have argued that the postmodern cosmologies provide evidence that mind was “there” all along. Here, Deacon differs. To him, it’s self-evident that mentality and end-directedness didn’t always exist. History and an open universe made it possible for mind-stuff to emerge. Like much of postmodern thought in physics and the life sciences, including Big Bang theory, a radical historicism holds sway.

It seems to me that intellectual historians might consider the worth of Deacon’s project, especially the way he frames the basic problem as a problem of value. While I’m not wholly uncritical, I do find persuasive his claim that the explanatory hole is a source – perhaps the

source – of irritation and corrosion outside the realms of science and philosophy. “Our scientific theories have failed to explain,” Deacon writes, “what matters most to us: the place of meaning, purpose, and value in the physical world.” “Is it any wonder, then,” he asks elsewhere, “that scientific knowledge is viewed with distrust by many, as an enemy of human values; the handmaid of cynical secularism, and a harbinger of nihilism”? (14, 22)

The suggestion here is that the explanatory hole is at the very root of conflict we call the culture war here at home, and internationally, the war on terror. It’s also at the root of our inability to confront climate change and the widespread collapse of living ecologies. What stubborn constituencies might be broken up, and what common grounds uncovered, were the dilemma more directly addressed, rather than being hidden behind homunculi?

_____________

Anthony Chaney (PhD, University of Texas at Dallas) is currently shopping his book, The Apocalyptic Encounter: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness, 1956-1967

.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I teach reformulations and challenges to Cartesian dualism in survey courses, from Spinoza tracts on substance to Locke and Diderot studies on “blindness” and Kantian noumenon (and the history of phenomenology). I attempt to **cohere** lectures on late nineteenth-century pragmatism, psychology, and legacies of phrenology with Neurology and Modernity and the history of neuropsychology. Mind-brain as a **function** of mind-body dualism, according to Deacon, seems in part explained by the **dynamic process** of **emergence theory** rather than **placeholders** such as survival, reproduction, homeostasis, or even **function.** Further readings on the history of neuropsychology as well as “quantum cognition” and related theory may or may not address facets of your aptly-put **explanatory hole** in course pedagogy and curriculum. Or is that **radical historicism?** Last month in Munich, those philosophy-physics conference debates on quantum mechanics and astrophysics may or may not have included Kuhn adherents. The debates resulted, however, in **historicist** challenges to the contemporary significance and insignificance of Karl Popper’s contributions, specifically “Science as Falsification.” I sincerely enjoyed the review.

Clarification: Mind-brain [connections] as a **function** of [studies on] mind-body dualism… Also, I presumed distinctions between Darwinian natural selection, including “chance,” in On the Origin of the Species and Darwinian sexual selection in The Descent of Man, although the latter is related to the former, both in Charles Darwin’s writings and the history of “Social Darwinism.”

Thanks for post Anthony, it’s interesting to find the hidden assumptions that are behind many of our ideas but I’m not sure I see the one you do (or Terence Deacon) when it comes to natural selection.

“Why are organisms striving to adapt, to organize themselves within their environments?”

The theory of natural selection says that organisms survive or more appropriately evolve not because of “intent”, “striving” or “purpose” but because they have the necessary physical properties (stronger immune system, prehensile tail whatever) that allows them to hunt more successfully, resist disease, escape predators etc. The theory doesn’t suggest that one can “strive” to adapt, it’s a matter of chance that one set of mutations will be successful but once surviving they continue to pass that genetic material on to succeeding generations. I’m not seeing the homunculi in your example.

Paul Kern, thank you for that clarification. And to be clear, that sentence you point out was me leaning too hard on the point rhetorically, not paraphrasing Deacon. I will admit with some embarrassment that it’s always been hard for me to grasp the distinction between “strive to adapt” and “adapt” – to eliminate intention from that verb. My practice has been to accept that difficulty as akin to the difficulty I have grasping certain mathematical concepts or concepts in physics. (I’ll keep trying.) It has been easier for me to grasp the use of the word “mechanism” to describe natural selection as making use of a machine metaphor … but then not knowing of any machine that was not meant to serve some purpose or function. And so seeing the word “mechanism” as a way to hide or bracket mind-stuff such as purpose and function.

Thanks for this interesting post. Looking for invisible homonculi would make for an very interesting project. But I think it would take some care.

Perhaps one approach would be to consider the histories of anti-reductionist methods and topics and their connections to specific values.

Another way to put this is: what are Deacon’s values and what are the values of his patrons such as the John Templeton Foundation?

I wonder about a couple of things here. As far as homunculi filling holes, it seems that the homunculi are there, or only possibly there in some but not all versions of evolutionary theory. For instance where adaptationism is not taken as the mechanism of evolution but, as for Darwin, variation within a generation and differential success of organisms at remaining alive and reproducing — then striving and teleology isn’t necessary. Just chance is enough. More recently versions of this can be found in Steven J. Gould and Richard Lewontin. But of course, teleology is and has been a big part of how evolution gets discussed. That’s part of what Gould ground his ax on especially in regards to evolution as discussed by Richard Dawkins.

As far as explanatory holes are concerned, I think there have been too many cases where the hole isn’t there for the hole to be the explanation of critique of science.

Here emergent properties give one answer for how homonculi aren’t necessary — as do dynamical systems. But other and earlier cases do too. In terms of teleology and goal direction: cybernetics seems relevant whether in terms of anti-aircraft guns, communication networks, neurology, genetics, computers, cognitive science or ecology.

In terms of non-reductionism we might consider gestalt psychology, general systems theory or homeostasis. When did defenders of these resort to homonculi and when did they find other means of defending their methods and sciences?

As far as distrust of science (or, earlier, natural philosophy) is concerned, I wonder if distrust declined or increased when scientists adopted non-reductionist or non-dualist methods and epistemologies. I would guess the answers would be non uniform and vary by historical context. Actually, I would guess that even within a single historical and national context that the interaction of distrust of science with reductionism/non-reductionism will generally have varied responses depending on the science. For instance compare the Nazi reactions to quantum mechanics to non reductionist biology or neurology.

Jamie Cohen-Cole’s concluding remarks on “varied responses” reminded me that Munich conference proponents of “Science as Falsification” included experimental physicists and loop quantum gravity advocates from around the world, despite efforts to reconcile LQG with string theory. Detractors of strict “Science as Falsification” included both theoretical and experimental physicists as well as philosophers (and historians of science) similarly from around the world.

a perhaps too-hasty reaction: it seems to me that intellectual historians should perhaps begin by pointing out that this line “Our scientific theories have failed to explain…what matters most to us: the place of meaning, purpose, and value in the physical world” — almost verbatim can be found in debates about the meaning of science in the late 19th century. the debates this post describes Deacon as engaging in are in important ways *the same* as debates that took place in the 1870s-80-90s. even the notion of emergence has real parallels with 19th century attempts to explain consciousness without giving up on science. lots has changed–science means something different now–but lots also has not changed.

which, i guess, makes me suspicious of the idea that this explanatory hole has any significant explanatory value in today’s culture.

…and that’s what i get for loading the page, waiting several hours, then reading and replying without reloading to check for new comments. 2nd to Cohen-Cole.

To clarify: Jamie Cohen-Cole’s argument is that an assessment of causes for a “critique of science” in history should not be solely reduced to an **explanatory hole.** Your point and suspicion is that the **hole** in question, as well as research into a given “critique of science” in history, do not provide “any significant explanatory value in today’s culture.”

I appreciate these comments very much, especially the several ways Jamie Cohen-Cole suggests for approaching these matters critically. He reminds that anti-reductionist efforts have a many-sided history. Deacon’s book, it seems to me, is one of many that have made an effort to naturalize mind in ways that don’t require a person, as Frank Zelko has put it, to surrender membership in a secular, rational, modern world. That effort “to explain consciousness without giving up on science,” as Eric Brandom concisely put it in his comment, have been going on for well over a century and I agree that this is a reason to be suspicious that resolving the explanatory hole is the solution to the kind of cultural conflict I mentioned.

Still, what draws my attention is how, despite all the decades, these matters continue to find mainstream expression. Just now I’m thinking about a speech made by the character played by Matthew McConaughey in True Detective. He and his partner are in the car, and he talks about human consciousness as a “tragic misstep in evolution” and people as “things” that labor under the impression that they’re “selves.” It was once thought that people would get used to this way of thinking. They don’t seem to have gotten used to it. Deacon’s book acknowledged that and explores another approach.

The Frank Zelko reference comes from his article surveying holistic thought, “‘A Flower is Your Brother!’ Holism, Nature, and the (Non-ironic) Enchantment of Modernity.” (2013) Intellectual History Review

Thanks for leading me to the Deacon book.

I’ve always thought that “survival” had been insufficiently historicized—particularly in the type of comparative histories that we find in other similar topics (e.g., “curiosity,” “objectivity,” etc.).

Does the “common-sense” acceptance of survival, striving (or the presence of objects persisting) bring with it the a priori argument that non-existence (or, the “void”) is somehow not “preferred” over being here (or there)?

Maybe it would asking too much for cultural and intellectual historians to proceed with their research without taking this as the universal consensus. Yet, it seems there are questions that can be raised nevertheless.

So, for example, more comparative historical studies on “survival” and “survivance.”