Editor’s Note: This is the third in a series of four biweekly guest posts by Sara Georgini. — Ben Alpers

He grabbed the Shinto priest’s camera and shoved past all warnings. Historian Henry Adams, still chasing peace nine months after the 1885 suicide of wife Clover, hiked up the Kamakura rooftop. Ahead lay the 43-foot Great Buddha (Daibutsu). At his step, wood porch tiles dipped to sag low. Nearby on John LaFarge’s wet canvas, the mammoth 13th-century bronze swayed against blue-white puffs of autumn sky. Bent double over a heavy lens, Henry Adams fought for balance in the Great Buddha’s shadow.

He grabbed the Shinto priest’s camera and shoved past all warnings. Historian Henry Adams, still chasing peace nine months after the 1885 suicide of wife Clover, hiked up the Kamakura rooftop. Ahead lay the 43-foot Great Buddha (Daibutsu). At his step, wood porch tiles dipped to sag low. Nearby on John LaFarge’s wet canvas, the mammoth 13th-century bronze swayed against blue-white puffs of autumn sky. Bent double over a heavy lens, Henry Adams fought for balance in the Great Buddha’s shadow.

Capturing nirvana—in a garden, temple, or Buddha’s smile—proved thornier than he anticipated. From his village vantage point, and “standing on my head at an angle of impossibility,” Adams wrote drily, “[I] perpetrated a number of libels on Buddha and Buddhism.” The 5’4” medievalist, a man who famously felt out of scale with modernity, learned that photographing non-western traditions

widened his historical perspective on the page. By the age of 48, Henry was a world-class traveler, and a picky tourist. Adams had grand-toured his way through a half-hearted lap of Berlin law school. He picnicked across Roman ruins during the American Civil War, and honeymooned (first-class) on the Nile. On most jaunts, Clover had been the primary photographer, snapping Karnak’s glory and New England revels. Now, deep in the ricepads and riverlands of rural Japan, her widower took up the craft. Moving from fashionable agnostic to open skeptic, Henry used photography to stage and interpret theatres of faith. Pulled together here as a pop-up gallery of his thoughts on eastern religion, Adams’s many pictures—which he variously shot, or commissioned—open a query: When we look at another culture, how do we choose what to see?

Like many Victorian elites who sought out Buddhist passivity in the wake of the Civil War’s hell, Henry had only a vague idea about the “Protestantism of the East” when he sailed from San Francisco. Once arrived in the “toy-like” country, Adams was not especially kind in describing the “oily” and “fetid” world that he encountered. But he was fascinated, and boasted enough souvenir sales receipts to bear the trip. Guided by Ernest Fenollosa

and William Sturgis Bigelow, Henry shopped his way through Japan; his “Expenses Notebook” tallied the modern equivalent of $250,000 spent on ivories, gongs, kimonos, scrolls, netsuke, and sets of “Satsumaware.” Notably, the wealthy skeptic splurged on all things touched by faith. When he wasn’t shoveling up lots from the bric-á-brac dealers via rickshaw, Henry visited and shot an album’s worth of temples, sacred groves, men and women worshipping, and religious landmarks.

Japanese language did not interest Henry, so cultural interpretation grew cloudier as he traveled. Despite washed-out roads and a cholera outbreak, Henry’s search for the fin-de-siècle nirvana continued daily. Sinking back into life abroad, he wrote few letters. Though he never said more than “Hei” or “Ha” (“Yes, indeed” or “Well, I see”), Adams’s sense of looking

—the traveler’s gaze—crystallized in Japan. A self-trained architectural analyst of medieval France, Adams saw that reading a cathedral’s bones was not the same as retracing the Shinto soul. He titled reference photos with the best-guess concision of a cosmopolitan scholar toiling on fellowship far from home: “Avenue of Buddhas,” “Avenue of Temples,” “Gate of Inner Temple.” By trip’s end, he was ready to study all religion from the outside, in. “Images are not arguments, rarely even lead to proof, but the mind craves them,” Adams wrote. His understanding of faith now hinged on image and perspective, not feeling or doctrine. Religion and art, for Henry, were one.

And what the camera told him, Henry believed. So he photographed monks and mortuary gates, temples and tombs. LaFarge sketched patiently, soaking up hours in each temple vista. By contrast, Adams tore through Japan’s many rooms of faith. His visual record of eastern religion—a western skeptic’s sustained stare—is unique. It is simultaneously a historian’s breakneck struggle for perspective, and a statement of agnostic bewilderment that such believers exist. Traveling on to Latin America, the South Seas, and back to Europe, Henry let his camera talk. His photos restage lost landscapes of Gilded Age faith, as one American confronted it: Shinto priests resplendent in full robes, mosque spires rimmed in sepia, dusty workmen resting at Ramesses’ toes, Tahitian royals at play, and a fleet of Fijian women dancing off the page. (Let me add a line to make a scholar’s heart sing: It’s all open for research).

Hailing from a family that produced several social historians of religion, Henry was the first to investigate fully Asia’s intellectual traditions. An eager patron of exotic ornaments to deck his new H Street townhouse, Henry made for a less generous critic of Japanese religion. Far away from the familiar flying buttresses of Gothic France, Adams dismissed the scarlet-and-gold curlicues of Shinto temples as too “baroque.” Holy sites often looked like “toys,” he wrote, but Henry adored the landscape—softer and greener than he had expected. At times, life in Gilded Age Japan was nearly nirvana-like, Adams thought.

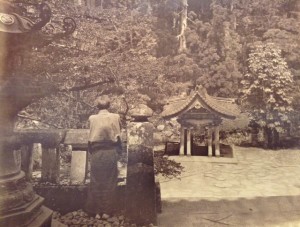

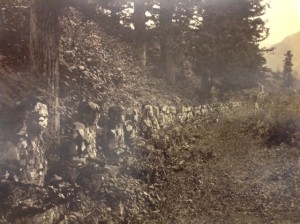

Two photos, serving as point and counterpoint, remind us why Henry Adams ventured there at all. Before the Buddhas, before he tried “saki,” before the moment when he “seized” the priest’s camera, Henry sent a terse commission to the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens regarding Clover’s memorial at Rock Creek Cemetery: “Nirvana.” Japan was a research trip, a chance to send back inspiration for the artwork. So here is one profile of nirvana, direct from Henry’s camera in Japan: A thinker, hunched in light and shielded from our view. And here is another model for Clover, not as one guardian but many—the Bake (Ghost) Jizo Trail of bodhisattvas—lining a narrow gorge near Nikko. In 1902, a flood ripped away or broke a third of the protector statues. In Henry Adams’s pictures, they still balance, and bend.

Two photos, serving as point and counterpoint, remind us why Henry Adams ventured there at all. Before the Buddhas, before he tried “saki,” before the moment when he “seized” the priest’s camera, Henry sent a terse commission to the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens regarding Clover’s memorial at Rock Creek Cemetery: “Nirvana.” Japan was a research trip, a chance to send back inspiration for the artwork. So here is one profile of nirvana, direct from Henry’s camera in Japan: A thinker, hunched in light and shielded from our view. And here is another model for Clover, not as one guardian but many—the Bake (Ghost) Jizo Trail of bodhisattvas—lining a narrow gorge near Nikko. In 1902, a flood ripped away or broke a third of the protector statues. In Henry Adams’s pictures, they still balance, and bend.

0