The following guest post is by my graduate student Meghan Hawkins, who is a social studies teacher at Normal Community High School in Normal, Illinois. This essay on Derrida is Meghan’s final paper for the “Philosophy of History and Historiography” course that is required of all our graduate students. She and her colleagues were charged with writing about a groundbreaking historian or theorist. I liked this essay so much I thought it deserved a larger audience than an audience of one.

The following guest post is by my graduate student Meghan Hawkins, who is a social studies teacher at Normal Community High School in Normal, Illinois. This essay on Derrida is Meghan’s final paper for the “Philosophy of History and Historiography” course that is required of all our graduate students. She and her colleagues were charged with writing about a groundbreaking historian or theorist. I liked this essay so much I thought it deserved a larger audience than an audience of one.

“As if from now on we didn’t dwell there any longer, and to tell the truth, as if we had never been at home. But you aren’t uneasy, what you feel – something unheard-of yet so very ancient – is not a malaise; and even if something is affecting you without having touched you, still you have been deprived of nothing. No negation ought to be able to measure up to what is happening so as to be able to describe it.”

– Derrida from At This Very Moment in This Work Here I Am [1]

To begin a biographical sketch of Derrida is to, in many senses, bear false witness against Derrida. Bear false witness in many senses. For with which of my senses am I qualified to bear witness? If one can even know someone (know of them [connaître]? To be familiar with them [also, connaître]? Or perhaps to have already been familiar with them at some time in the past [again, connaître, yet in the past tense]? But if instead, it is the knowing of what a person is [savoir]? Or in its past tense to have found out about the person [savoir]?). What then do I know of Derrida?

On the surface, a further level of irony exists in the biography of a poststructuralist, a school associated with the death of the author. Although the work of poststructuralist Roland Barthes likely influenced his work, this aspect of post-structuralism is often misattributed to Derrida. While Derrida maintains that when deconstructing a text “there is nothing outside of the text” [il n’y a rien hors du texte], he also concludes that the life of the author is not without meaning. When writing about Nietzsche in 1976, Derrida himself said,

We no longer consider the biography of a ‘philosopher’ as a corpus of empirical accidents that leaves both a name and a signature outside a system which would itself be offered up to an immanent philosophical reading – the only kind of reading held to be philosophically legitimate… [2]

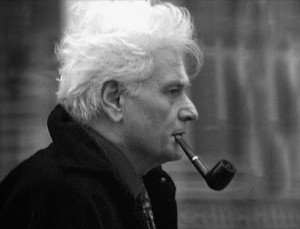

The influences of Derrida’s personal biography on his intellectual biography cannot be considered “empirical accidents.” Born to a family of Sephardic Jews in 1930 in French controlled Algeria, Derrida biographers Jason Powell and Benoit Peeters note that later in life Derrida frequently recalled his hybrid background. Expelled from school at age 12 due to his Jewish background during the Pétainization of Algeria in World War II, Derrida would eventually end up at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris where he would begin his formal studies of Husserl. From modest backgrounds, Derrida would go on to engage in “what has proved to be one of the most stunning adventures of modern thought” according to Derrida scholar Peggy Kamuf. [3] Derrida’s childhood experiences seem to exist in a space between the binary oppositions his scholarly work would seek to move beyond. Although Jewish, his family referred to his circumcision as his “baptism.”[4] Although Algerian, Derrida and his family sought to be French, in spite of the fact that French culture would never allow for Algerians to be truly French. Linguistically, Derrida grew up speaking accented and idiomatic Algerian French, yet as biographer Powell explains, “On behalf of France and Paris he [Derrida] contested his own voice throughout his life, held it back, his accent, his native language and idiom. His desire to contest everything, even himself, in the name of a higher standard of purity is very characteristic.”[5] His biography reads as a story of margins: Jewish in a land of Muslims, Algerian far from the metropole

, a philosopher questioning traditional metaphysics, a French academic lecturing in foreign countries. With hindsight, Derrida’s life left traces (both literal and in the Derridean sense) across his academic career.

Derrida’s writings are far too prolific to list individually, and his influence in the humanities is impossible to succinctly describe. [6] Derrida’s thinking is heavily influenced by the works of Nietzsche, Husserl, Levinas and Saussure. In fact, many of Derrida’s early works are direct engagements with the texts of these philosophers. Much as Saussure is credited with initiating the structuralist approach to textual analysis and critique, Derrida is one of the central originators of post-structuralism. Derrida’s work was a product of the attitudes of the 1960s and simultaneously moved beyond existing modes of critique. For example, Derrida’s work represents a crisis within structuralism, despite being written during an era when structuralism was still popular. For structuralists, symbolic structures govern behaviors. These structures are represented through signs and tokens, which are unrelated to individual choices. In other words, structures exist regardless of specific circumstances and independently of individuals. Derrida’s work both deconstructs and destroys many of the key features of structuralism. At the core of Derrida’s critique of structuralism is the fact that the theory does not take into account time, nor do structures seem capable of changing. [7]

Derrida’s work seeks to escape from the history of metaphysics, but finds itself trapped in the existing structure which values what is present, establishes sense based on opposition and promises immediate access to meaning. Given these constraints, Derrida attempts to access his ideas through his own lexicon (although Derrida would certainly disagree with this terminology). Crucial to an understanding of Derrida’s philosophy is the term différance. Created by Derrida, all signs constitute différance in that signs are not the thing to which they refer. What then is différance? Derrida proffers the following “definition” (my quotes) of the term: “Différance as temporization, différance as spacing.” [8] In order to understand this definition, one must refer to the origin (Derrida would shudder at my word choice) of différance, which comes from the French verb différer, which means both to defer and to differ. All signs defer (meaning they have temporality) and all signs differ (creating a gap, or space, between the sign and what it means). For example, you might tell a friend “I like your new sweater.” At the point of saying “new” your friend does not know what you are referring to – because meaning is deferred. The meaning conferred by “new” comes from “old” and that of “sweater” comes from an understanding of other possible tops (blouses, jackets, sweatshirts…) – because all signs differ. Even within a term, meaning is inherently unstable. In this example, “new” could mean “newly acquired,” “newly made,” or “of a new style.” Like all of Derrida’s terms, différance has multiple layers of meaning. In spoken French/English, difference and différance are homophones, marking the distinction between speech and writing. According to Derrida, différance is “no longer simply a concept, but rather the possibility of conceptuality, of a conceptual process and system in general.” [9]

Différance rejects the oppositions we have unquestioningly accepted as the basis for language. As such, Derrida realizes this “makes the thinking of it [différance] uneasy and uncomfortable.” [10] Derrida contends that signs do not convey meaning in the way intended by the original author. What is missing from a text becomes as important as what is there. As Derrida clarifies in “Différance:”

Thus one could reconsider all of the pairs of opposites on which philosophy is constructed and on which our discourse lives, not in order to see opposition erase itself but to see what indicates that each of the terms must appear as the différance of the other, as the other different and deferred in the economy of the same (the intelligent as differing-deferring the sensible, as the sensible different and deferred; the concept as different and deferred, differing-deferring intuition; culture as nature different and deferred, differing-deferring;… [11]

Given the structure of language, it is not possible to escape these opposites – once the need of speech is accepted, these opposites become unavoidable according to Derrida. There is, however, a level of meaning which can be uncovered through an analysis of the space beyond (again, Derrida would shudder at my word choice) or spectrality of existing signs. For Derrida, words leave behind a trace, which itself can never become a meaning, as it exists in différance rather than in presence. To uncover the logic of the trace, one must deconstruct a text.

Without différance, there is no deconstruction, the term which has become inexorably linked to Derrida – his very own trace if you will. Like most of Derrida’s contributions to post-structuralism, a concise definition of deconstruction is intentionally elusive. Derrida scholar Nicholas Royle eventually proposes the following definition based on a close reading of Derrida’s many descriptions of the term at the end an eleven page letter entitled “What is Deconstruction?”:

Deconstruction n. not what you think: the experience of the impossible: what remains to be thought: a logic of destabilization always already on the move in ‘things themselves’: what makes every identity at once itself and different from itself: a logic of spectrality: a theoretical and practical parasitism or virology: what is happening today in what is called society, politics, diplomacy, economics, historical reality, and so on: the opening of the future itself. [12]

Crucial to this description is what deconstruction is not. Despite modern understandings of deconstruction, Derrida clearly states in “Letter to a Japanese Friend” that “Deconstruction is neither an analysis nor a critique and its translation would have to take that into consideration… Deconstruction is not a method and cannot be transformed into one.” [13] Derrida himself describes the style of deconstruction as, “From the interior of the closure, one can only judge its style in terms of received oppositions. One will say that this style is empiricist and, in a certain way, one would be right. The exit is radically empiricist.” [14] This embodies the complexity of Derrida’s work. On the one hand, he poses a definition of deconstruction that uses terms that can only be defined by their opposites: empirical (transcendental or theoretical), interior (exterior), exit (is he referring to the noun? the verb?). At the same time, his theory of deconstruction proposes to move beyond the very terms that he uses to define it.

The process of how deconstruction takes place is, perhaps, more accessible. First, deconstruction is the deconstruction of a text. Deconstruction interlaces different layers of meaning: “the dominant interpretation” (the meaning of a text according to critical, academic scholarship) is re-examined in order to “open a text up to blind spots or ellipses within the dominant interpretation,” explains Critchley. [15] Deconstruction destroys the traditional understanding of boundaries, while residing entirely within the text, for as Derrida (in)famously explained, “There is no outside-text” [il n’y a pas de hors-texte]. [16] Within the text, deconstruction moves the reader to a place that is other to existing logocentrism, a place where the reader is then able to see beyond the intended meaning of a text. While many critics of Derrida have argued that deconstruction allows for any reading of a text, Derrida disagrees. While signs may not convey meaning in the manner intended by the author, Derrida chastised his critics: “one could indeed say just anything at all and I have never accepted saying, or being encouraged to say, just anything at all.” [17] Deconstruction was not limitless interpretation, even when labeled as such by critics.

Despite this admonition, deconstruction opens itself to somewhat obvious criticism. Many on the right rejected deconstruction outright, as Powell scathingly explains, “due to the frustration which conservative, authoritarian minds feel when they find that their ideals are truly real only because they insist that they are real, and that in fact they are spectral ideals for a half-present world.” [18] Since Derrida claims that “structures and systems on the subject of being are always faulty,” [19] it is understandable that structuralists would fundamentally disagree with Derrida’s break with metaphysics. At the same time, Derrida’s theories presented substantive concerns for many on the left. If signs do not convey the intended meaning of the author, then any study of signs (such as anthropology, literature, history, etc.) can be seen as meaningless. For others on the left, “deconstruction seemed to have a paralyzing effect,” as historian Andrew Hartman explains. [20] “By militating against the possibility of intelligible communication, it limited the prospects for justice, which demands agreed-upon conceptions of the good life. In short, deconstruction negated the utopian possibilities that had long inspired a universalist left.” [21]

The reputations of Derrida and deconstruction were also dealt serious blows in the wake of several scandals. In the late 1980s, deconstruction was drawn into the renewed debate over fascism. Derrida was called upon to explain his philosophical links to Heidegger and Hegel, whose works were linked to the ideology of the Nazi Party. Then, in 1988, literary critic and noted deconstructionist Paul de Man’s collaboration with the Nazi party in occupied Belgium was revealed posthumously. Derrida, and other deconstructionists, countered accusations that deconstruction was born from fascism and/or fashioned fascist ideology. As Hartman states, deconstructionists “argued that deconstruction was an implicit repudiation of fascism” that provided “a bulwark against the rigid ideologies that make totalitarianism possible.” [22] In 1992, Derrida would again be embroiled in controversy, when his nomination for an honorary degree from the University of Cambridge was publically contested in the media. [23] Deconstruction itself came under attack in the Sokal hoax of 1996. [24] By the late 1990s, opponents had painted Derrida as a nihilist with no ethics who was responsible for turning philosophy into a joke. [25] By the time of Derrida’s death in 2004, there was no shortage of critiques.

Despite a vast body of works that engage Derrida, there are large gaps in scholarship. As scholar Joshua Kates, whose work focuses on French poststructuralists explains, “not only is there no consensus about the validity of Derrida’s interpretations, but perhaps more gravely, no model, no paradigm for interpreting Derrida’s own thought is at present available that has even the potential to someday resolve this controversy.” [26] Nonetheless, Derrida’s work has permeated across the humanities, including history. For example, in the preface of Frontiers of the Historical Imagination Kerwin Klein thanks his advisor for convincing him that he could read Derrida “without leaving history behind.” [27] Klein’s analysis demonstrates how emphasizing different words within Fredrick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis results in significantly diverse conclusions. [28] Furthermore, Klein’s entire work is based on loosening (if not breaking down) binary understandings of frontier/civilization, enslavement/freedom, and happy/unhappy outcomes in our understanding of American frontier history.

Derrida’s insistence on giving voice to the other directly influenced post-colonial studies, legitimizing the study of colonialism from the perspective of the colonized and not just the colonizer. Here again, however, one sees the paradox of Derrida’s work: while deconstruction allows for an understanding of the other, deconstruction also infinitely displaces power structures. Once the traditional hierarchy has been “flipped” (in this sense, to view history from the perspective of the colonized), one must again displace the center (returning to the perspective of the colonized, however, with new insight which would generate an altered understanding). While post-colonial authors like Edward Said and Franz Fanon targeted specific colonial regimes in an attempt to influence change, Derrida’s critique is leveled at the metaphysics which places European colonizers at the center of discourse, in a preferred position of singularity and therefore power. As Derrida explains in Margins of Philosophy:

Metaphysics- the white mythology which reassembles and reflects the culture of the West: the white man takes his own mythology, Indo-European mythology, his own logos, that is, the mythos of his reason, for the universal form of that he must still wish to call Reason… White mythology – metaphysics has erased within itself the fabulous scene that has produced it, the scene that nevertheless remains active and stirring, inscribed in white ink, an invisible design covered over in the palimpsest. [29]

In the specific case of post-colonialism, différance has political significance. The spoken and written term possess both sameness (as homophones) and difference (in spelling). Post-colonial scholars like Robert J.C. Young contend that the term différance “perfectly describes the political condition of a minority group: a minority wants to make a claim that according to the classical account of identity is impossible, namely that it is the same and different.” [30]

Derrida’s work allowed for both a breaking of traditional binary oppositions and a reworking of group politics. As such, it provided a theoretical foundation for feminism as well as post-colonialism. The works of both Joan Wallach Scott and Judith Butler are heavily influenced by Derrida’s ideas. According to Scott, modern feminist analysis is based on the assumption that since “meanings of concepts are taken to be unstable, open to contest and redefinition, then they require vigilant repetition, reassertion, and implementation by those who have endorsed one or another definition… meanings are not fixed in a culture’s lexicon but are rather dynamic, always potentially influx.” [31] Scott goes onto to address binary opposites, succinctly detailing the basis of Butler’s later work:

Positive definitions rest always, in this [post-structuralist] view, on the negation or repression of something represented as antithetical to it… Although some opposition pairs seem to recur predictably in certain cultures, their specific meanings are conveyed through new combinations of contrasts and oppositions. Contests about meaning involve the introduction of new oppositions, the reversal of hierarchies, the attempt to expose repressed terms, to challenge the natural status of seemingly dichotomous pairs, and to expose their interdependence and their internal instability. [32]

For the entire field of feminist and gender studies, deconstruction offers a theoretical starting point for an analysis of gender in discourse. Derrida himself wrote several essays on feminism, including “At This Very Moment in This Work Here I Am” in 1987. This latter part of the essay features a dialogue that deconstructs the phrase “He will have obligated” [Il aura obligé] to show the depth with which the masculine is favored over the feminine in the very structure of language. [33] As Butler proves, terms like “nature” and “sex” are not facts, as they are commonly understood, but concepts with histories, articulated through language, and therefore subject to multiple understandings throughout time. Sounding strikingly like Derrida, Scott explains, “If sex, gender, and sexual difference are effects – discursively and historically produced – then we cannot take them as points of origin for our analysis.” [34]

The use of deconstruction in politically charged fields like post-colonialism and feminism occurred at the same time that Derrida’s works themselves became increasingly political. Yet, in typical Derridean fashion, Derrida himself never wrote a work on political philosophy. [35] Derrida’s colleague and biographer Geoffrey Bennington contends that part of the reason that Derrida avoided an explicit analysis of politics was in itself “‘political’: a sense of political strategy and solidarity may have dictated prudence about criticizing the arguments of the Left.” [36] At the same time, since deconstruction targets existing hierarchies of power, deconstruction is inherently political. Beginning in the 1990s, Derrida openly opposed a range of issues: the death penalty, European racism, European immigration policy, apartheid, totalitarianism, censorship, and the political discourse in response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11. [37] Derrida’s later work focused on mourning, death, ethics and justice. As Butler explains in her obituary of Derrida, Derrida was clear that “as an ideal, it [justice] is that towards which we strive, without end. Not to strive for justice because it cannot by fully realised [sic] would be as mistaken as believing that one has already arrived at justice and that the only task is to arm oneself adequately to fortify its regime.”[38] Butler’s poignant obituary is a testament to Derrida’s legacy. As she so eloquently concludes, Derrida “not only taught us how to read, but gave the act of reading a new significance and a new promise.” [39]

[1] Peggy Kamuf, Derrida Reader: Between the Blinds (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 403.

[2] Benoit Peeters, Derrida: A Biography (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 60-61.

[3] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, vii.

[4] Jason Powell, Jacques Derrida: A Biography (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006), 12.

[5] Powell, Biography, 13.

[6] Some of Derrida’s most noted works include: “Introduction à L’Origine de la géométrie par Edmund Husserl” (1962), Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences (1966), Of Grammatology (1967), Writing and Difference (1967), Dissemination (1972), Spurs (1978), The Post Card (1980), “Living On: Borderlines” (1986), Du Droit à la Philosophie (1990) and Spectres of Marx (1993).

[7] Powell, Biography, 65.

[8] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, 61.

[9] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, 63.

[10] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, 65.

[11] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, 70.

[12] Nicholas Royle, ed., Deconstructions: A User’s Guide (New York: Palgrave, 2000), 11.

[13] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, 273.

[14] Simon Critchley, The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1999), 14.

[15] Critchley, Ethics, 23.

[16] Critchley, Ethics, 25.

[17] Critchley, Ethics, 24.

[18] Powell, Biography, 5.

[19] Powell, Biography, 74.

[20] Andrew Hartman, A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 240.

[21] Hartman, War, 240.

[22] Hartman, War, 241.

[23] Powell, Biography, 187.

[24] Hartman, War, 251.

[25] Powell, Biography, 3.

[26] Joshua Kates, Essential History: Jacques Derrida and the Development of Deconstruction (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2005), xviii.

[27] Kerwin Lee Klein, Frontiers of Historical Imagination: Narrating the European Conquest of Native America, 1890-1990 (Berkley: University of California Press, 1997), x.

[28] Klein, Frontiers, 18.

[29] Royle, User’s Guide, 188.

[30] Royle, User’s Guide, 203.

[31] Joan Wallach Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 5.

[32] Scott, Gender, 7.

[33] Kamuf, Derrida Reader, 505.

[34] Scott, Gender, 201-202.

[35] Tom Cohen, ed., Jacques Derrida and the Humanities: A Critical Reader (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 193.

[36] Cohen, Humanities, 199.

[37] For example, Giovanna Borradori, Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

[38] Judith Butler, “Jacques Derrida,” London Review of Books 26 no. 21 (2004): 32, http://www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n21/judith-butler/jacques-derrida.

[39] Butler, Derrida, 32.

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks, Meghan, for crafting a lucid and comprehensive primer on Derrida’s many arcs of thought. I look forward to seeing how Derrida’s theories shape your continuing research. Thanks for contributing here!

Can something non-lucid be made lucid? I doubt it, and in the case of derrida i am sure of it. but that’s the beauty of this guy’s scam. his writings are so unintelligible and incoherent and yet seemingly so packed with “wisdom” that anyone can believe they see themselves in his writings and so can feel a sense of vindication about their own ideas when in fact the man is saying nothing in particular. In reality, it’s just bloated double-talk.

It’s a good con and nice work if you can get it but in the end i am reminded of the emperor’s new clothes.

as for me, i’m in einstein’s corner on this: “Any fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius-and a lot of courage-to move in the opposite direction.” sorry folks but that’s how i see it.

no offense to the student

peace

What a crappy, passive-aggressive comment — three paragraphs of snide, barely-lucid, bloated insults that attempt to delegitimize this scholar’s academic interests and her careful work right out of the gate, followed by a gutless little disclaimer: “no offense to the student…peace.”

Surely there’s some (in)apt Dylan lyric you could have cryptically quoted instead in order to feign intellectual depth, as is your usual custom.

As a newcomer who should be warmly welcomed to our discourse community, Meghan may not know your predictable trolling habits — but the rest of us do, and we’re not impressed. Patient, tolerant, sometimes (most of the time, in fact) indifferent — but definitely. not. impressed.

And even if “we” here is just me and the dormouse in my pocket, that’s still more critical acumen than you can muster in a month of Sundays. So piss off.

Waaah. Big words and complicated phrases translated from French are haaaard. It has to be a scam, otherwise he’d write in pretentious, faux-new-agey English, right?

Peace.

@ Kevin Gannon:

I have basically no opinion on Derrida, mainly because I’ve read almost nothing of him.

I do have a rough opinion, however, on the issues of difficulty and clarity. What is objectionable is not difficulty but unnecessary difficulty: saying something more opaquely (to use Andrew’s word from below) than is necessary. Whether Derrida is culpable on that score I don’t really know.

P.s. I happened to read a piece ( a book review) in Boston Review not long ago that ended with a reference to “the vulnerability of clarity” (I think that was the phrase). Something to that, istm.

Bravo! Well done. I’ve read *Margins of Philosophy,* “Différance,” and other selections years ago (1999-2000), but this essay nicely summarizes the major points of his thought—integrating the the author and his work with what followed. – TL

Meghan, this is really great. I particularly appreciate how you have highlighted the theoretical connections between deconstructionism and post-colonialism, and I’d be very interested to hear more of your thoughts about this.

In response to Publius @ 4:46: You’re not the first person to have this opinion of Derrida, and you won’t be the last. It’s long been conventional wisdom. Perhaps it’s the right opinion–Derrida is notoriously difficult so even though most people with this conventional opinion of Derrida have never read any Derrida aside from a few infamous passages, a few people who have patiently grappled with him have concluded his work is opaque nonsense. But… it would have been more gracious of you to actually read and respond to Meghan’s careful and smart analysis of Derrida than to use her essay as an occasion to reinforce an opinion we have all already heard many times over.

I’m a total dork for historiography, theory, and–especially–poststructuralism–and this is one of the best reflections on Derrida’s thought I’ve ever read. In particular, your insights on the ways in which a Derridean approach complicates postcolonial thought are really important and well-put. Thanks for publishing this!

Thanks for allowing it to be put up Meghan. You’ve provided some clarity to the obfuscation of Derrida at least for this individual. Welcome to the blog as well.

Meghan, this is a wonderfully rich discussion, and a beautifully written one, too. I hope that you continue to work on this material!

A few thoughts for future research.

1) Your emphasis on differance’s temporality is very sophisticated, and definitely in line with recent readings of Derrida. (Perhaps most importantly: the work of Fred Moten and Nahum Chandler).

To go further with this, it might be productive to see Derrida as a thinker primarily in conversation with three texts: Heidegger’s Being and Time, Freud’s “Beyond the Pleasure Principle,” and Walter Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence.” Each of these texts maps out a different approach to non-standard temporality, and each sees the experience of time and the horizon of death as the starting points for understanding the human condition.

Today, it is very common to see Derrida discussed as if he were arguing exclusively with Heidegger, which leads to all sorts of distortions. It is also common to see Derrida as fundamentally attuned to wrestling with the work of Emmanuel Levinas, which is equally misleading.

At the same time, the later JD *is* often grappling with the thought of Levinas, and particularly with Heidegger as the representative of a certain “end of philosophy”––the completion of metaphysics as far as it can go––and with his own ambivalence about standing at the end of the end of philosophy. “Ending” thus becomes an important theme in his work.

2) An argument could be made that deconstruction was more methodologically coherent than its critics contend. It involves a series of moves that tradition-minded scholars often treat skeptically––such as reading for “gaps, silences, and echoes” in texts, or thematizing “minor” practices in a manner previously reserved for “major” ones.

3) Derrida’s importance for feminist theorists, especially, had a lot to do with their common engagement with the philosophy of law. It is really fascinating to read “Force of Law,” Derrida’s 1989 lectures on justice and jurisprudence and the responses from Judith Butler and Drucilla Cornell.

It seems quite clear to me that these conversations had, in the immediate background, feminist engagements with very material and practical dimensions of law and jurisprudence: the laws covering reproductive rights, pornography, legal constructions of the body, resurgent debates on eugenics of the 1970s-80s, etc.

It is frustrating to read so often that deconstruction was a purely mandarin activity removed from earthly and fleshly concerns and conducted in the heaven of ideas. I think the case can be made that because deconstruction spoke to so many feminist, queer theoretical, and anti-racist projects––each of which included powerful challenges to the legal status quo, as well as political initiatives conducted through the courts and law reviews––the intellectual hostility to Derrida has often reflected the anxiety about white male gatekeepers in regard to such projects.

4) It would be really nice to read your thoughts on Derrida and American pragmatism. The connection has been posited many times, but I have never been sure that it is really so strong. The papers of Richard Rorty might be very useful in this regard, if you are thinking about archival research down the road.

Also worth pondering: the connections between Derrida and post-World War II American New Criticism. Consensus literary scholars in the 50s and 60s also believed that “nothing was outside the text”–in order to reclaim ground from the Marxist-inflected literary criticism of the 30s that kept on insisting that literary critics link acts of writing to larger political and economic issues.

There is a subtle but powerful strain of academic conspiracy theory (to which I partially subscribe) that sees the vogue for Derrida in the US academy as a function of New Critic-trained liberals to embrace a kind of anarchic epistemic radicalism while avoiding “real politics.” This would be a very interesting critique to research and plot out–it surfaces in the writing of Said, and in the polemics of some of the adherents of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who often saw themselves as engaged in a zero-sum contest with Derrideans for control of the future of the humanities.

5) Finally: some contemporary figures who might be seen as heirs to Derrida whose work I am sure you would find fascinating: Giorgio Agamben, Bernard Stiegler, Rei Terada, Gil Anidjar.

Anyways, sorry for this too-long comment. This is really great work! Thanks for sharing it with us.

PS: Lorenzo Fabbri, The Domestication of Derrida: Rorty, Pragmatism and Deconstruction and Edward Baring,The Young Derrida and French Philosophy, 1945-1968 are both worth your while.

I’m glad Kurt weighed in here. I don’t think I was aware at all of the possible connections between Derrida and the New Criticism, so the two paragraphs at the end of point (4) were esp. interesting, to me at any rate.

Also, as everyone else has already said, Meghan Hawkins’s essay is very good. In particular I like its opening four paragraphs, the very first paragraph, it seems to me, being a successful effort to mimic (or maybe gently poke fun at?) Derrida’s own style (to the v. limited extent I know what that is).

I do have one question about the Algerian angle. France considered Algeria — and made it so by statute — an integral part of metropolitan France; it thus had a different

legal status than most of the rest of the French overseas empire. That, coupled with the general French assimilationist ideal, would have made it possible, istm, for someone of Derrida’s origins to have become “truly French” in the cultural and almost every other sense. I don’t know much about this, but I’m sure it’s explored in the biographies. (Camus is another well-known example of an Algerian-born French intellectual who rose to the heights of the literary world, but that may well be where the similarities between Camus and Derrida end.)

On **later JD** and **différance as temporization:** this intriguing essay reminded me of Peggy Kamuf’s “The Time of Marx: Derrida’s Perestroika,” published two years ago in the Los Angeles Review of Books, which wove passages from the Edward Baring study with Kamuf’s account of an English translation of Spectres de Marx.

I appreciate all of the thoughtful responses to my essay.

A special thanks to Kurt (7) for the detailed feedback and suggested readings.

Regarding the question posed by Louis (8) on Derrida’s Algerian origins: both Powell and Peteers stressed that Derrida never felt certain about his French identity. Having studied in France, my wording was likely shaded by my contemporary understanding of French culture and attitudes towards immigrants.

Thanks for the clarification on that point, Meghan.