Guest Post By Ryan Purcell, Assistant Book Review Editor

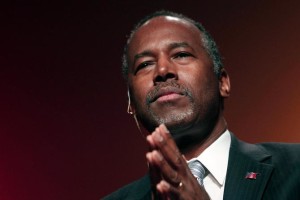

It presupposes many things to say that Ben Carson is the conservative black counterpoint to Barack Obama, which much of Carson’s constituency thinks he is. (See Jelani Cobb, “Ben Carson’s exonerating Racism,” The New Yorker, 9.22.15) First, it assumes that Obama is indeed liberal, which is a matter of perspective. But more importantly it means that Carson represents (or would, if he is elected) the lion’s-share of black voters that are not currently satisfied with their representation in the White House. While this constituency may be a minority, its voice is strong enough to push Carson to the top of the polls in the Republican primary race.

And what a curious race altogether. The recent political debates present a wide array of presidential hopefuls as diverse in their occupational backgrounds as their skin color.  Leading candidates, in the Republican race at least, are not career politicians but private sector professionals. Ben Carson is a renowned physician, Donald Trump is a financier and television personality. Bernie Sanders in the Democratic race, a self-identified socialist, also fills this unorthodox mold, as does the progressive rhetoric espoused by Hilary Clinton. This unconventional representation may reflect the dissatisfaction voters feel for a regularly inactive Congress, gridlocked in partisan divide. So early, though, such symbolism is doubtful to pan-out as substance.

Leading candidates, in the Republican race at least, are not career politicians but private sector professionals. Ben Carson is a renowned physician, Donald Trump is a financier and television personality. Bernie Sanders in the Democratic race, a self-identified socialist, also fills this unorthodox mold, as does the progressive rhetoric espoused by Hilary Clinton. This unconventional representation may reflect the dissatisfaction voters feel for a regularly inactive Congress, gridlocked in partisan divide. So early, though, such symbolism is doubtful to pan-out as substance.

More curious is the racial representation of these candidates. While Democrats present an all-white cast, Republican candidates are multi-racial. Ben Carson is black; Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz are Latino (Cuban and Cuban-Spanish descent respectively). Surely we should not take this to mean that Republicans are somehow more attuned to the interests of black and latinos, or are more representative of these constituencies, than Democrats. Yet purely descriptive representation is not entirely devoid of substance. Ben Carson is not a token black man in the Republican line-up, nor are Rubio and Cruz — or Bobby Jindal for that matter (the Indian American governor of Louisiana who only dropped out recently) — strictly symbolic of conservative diversity politics. Nor is their presence part of a GOP maneuver to wrangle minority votes. The diversity of Republican presidential candidates speaks to a vocal constituency of equally diverse conservatives. Black conservatives exist. Indeed, the only black man on the Supreme Court is among the most conservative. Descriptive representation is clearly substantive to some degree, yet this relationship is problematized by the socio-economic composition of constituencies.

To be black in American is to be naked, Ta-nehsi Coates asserts in Between the World and Me: “[T]he nakedness is the correct and intended result of policy, the predictable upshot of people forced for centuries to live under fear. The law did not protect us. And now, in our time, the law has become an excuse for stopping and frisking you, which is to say, for furthering the assault on your body.” Descriptive representation is substantive in that representatives share the racial experience of their constituents. This is not to essentialize African American voters, however, but shared racial identity between representatives and constituents suggests a level of trust that cannot be achieved otherwise. Ben Carson, for example, knows what it means to be black American; he has ostensibly felt the nakedness and fear which Coates describes. The same might be said for Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz and their Latino constituency. The presence of blacks and Latinos in government might ultimately lead to better representation, argues political scientist Michael Minta. He describes ‘strategic uplift’ as the means of providing a voice to underrepresented and marginalized communities that are not normally included in the public-policy-making process. This formula calls for a direct solution: Elect more blacks and Latinos. But does political partisanship among blacks and Latinos vary according to socio-economic status?

The erosion of the middle-class since the 1980s has resulted in the economic polarization of black America: there has been both a growing black middle-class (albeit increasingly insecure), and a growing black underclass, vulnerable to destitution. Ben Carson falls well within the former group. His socio-economic background does not align with most Americans largely, let alone black Americans. The same, however, could be said for Barack Obama. Both were raised in solid middle-class families, educated in elite institutions, and both were successful in their respective pre-political fields (law and community organizing, medicine). So why not a President Carson? Isn’t he the conservative black counterpoint to Obama? The more an African American believes their access to resources and opportunities are linked to those of racial justice as a larger movement, the more they will consider their racial group’s interests in evaluating political choices. This is what political scientist Michael Dawson calls the ‘black utility heuristic’. Moreover, Dawson finds, black political partisanship is determined by the ability of a party to actively further black interest. Though the majority of black votes are cast for Democratic candidates, today one third of African Americans identify as conservative.

Ben Carson is the latest example in a long line of black conservative politicians – which include Colin Powell, Clarence Thomas, and Edward Brooke (a prominent Republican Senator from Massachusetts in the 1960s and 1970s). Despite this linage, the economic vulnerably of black Americans in the current post-recession economy ensures black votes for the Democratic Party regardless of descriptive representation. With this in mind, we can see that descriptive representation is symbolic except when the socio-economic status of the constituency is vulnerable.

In the 2016 Presidential election racial description will remain a key issue which voters will consider when casting their ballots (perhaps equally important is the question of gender, as seen in the candidacies of Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina). Underlying both categories, however, the socioeconomic vulnerably of constituencies will be the most decisive factor of the election. In this light, a President Carson seems like a long shot. As long as the Republican Party platform champions free-market policies, while stripping Civil Rights legislation, removing the protections against discrimination and racial inequality, a black conservative candidate is unlikely to garner black votes. If Ben Carson is the counterpoint to Obama, it is an impossible position. – See more here.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Fascinating post, good to contextualize Carson within a broader lineage in black conservatism. I would be careful though with how Latina/os are described here, as a separate racial identity and not an ethnic / cultural category. It’s a common mistake that erases the complex processes of racial identification among Latina/os: many of whom identify and can pass as white (see Cruz and Rubio) , some of whom do not at all and embrace their blackness or brownness.

I confess to having read this post very quickly, but I can’t imagine why you are mentioning Edward Brooke in the same sentence as Clarence Thomas. Brooke was a moderate-to-liberal northeastern Republican of the sort that virtually no longer exists in the Republican Party today. I am reasonably sure Brooke would have strongly disagreed with Clarence Thomas’s opinions and outlook on about ninety percent of issues.

“. Both were raised in solid middle-class families…” No, Obama’s mother was a college graduate; Carson’s an illiterate domestic servant. That difference and the difference in religiosity is important for Carson’s white supporters, fitting the rags to riches narrative. Both were raised by mothers who had high expectations for their sons, both had fathers who were bigamists, both families were at times on food stamps.