The most recent post by Ben Alpers about September 11, 2001 and the shadow it casts over recent history has prompted me to think about the recent history of the American South, a region near and dear to my heart. More specifically, it has me thinking about the role of magazines in attempting to craft a different perception of the American South, compared to what most Americans are used to thinking about. Magazines as sources of intellectual debate and ferment are, of course, a tradition of the field. One could not imagine saying much about the history of the United States after 1960 from an intellectual perspective without citing, for example, The New York Review of Books or Commentary. Indeed, one of the plenary sessions at this year’s S-USIH conference covers the history of “little magazines.” Likewise, it will be difficult to write or talk about the intellectual history of the American South since the 1980s without mentioning magazines such as Oxford American, or for that matter, several other periodicals I like to think of as “little magazines of the South.”

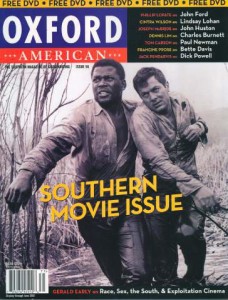

The debate over Southern identity and Southern values since the end of the Civil Rights Movement is one that deserves greater attention within American intellectual history. This attention is slowly starting to grow, seen in books such as Tara Powell’s The Intellectual In Twentieth-Century Southern Literature and Zandria Robinson’s This Ain’t Chicago. And as I’ve argued elsewhere, the 1970s were a period of considerable debate for African Americans and Southerners (of course many African Americans have always been, and remain to this day, Southerners) about the future of their cultures and traditions.  Oxford American, a magazine started in 1992, has served as one such place for debate about the future—and the past—of the South.

Oxford American, a magazine started in 1992, has served as one such place for debate about the future—and the past—of the South.

Of course Oxford American had some predecessors. Magazines such as Southern Exposure, started in 1973 and including among its founders Julian Bond, had for years presented a different kind of South from the stereotype of a conservative and traditional region seen in most media representations of the region. For intellectual historians, especially those of the South, it’s critical to consider how magazines such as Southern Exposure or Oxford American¸ just to name the most notable ones, served as spaces within which Southern liberals, progressives, and radicals could present their version of the American South to readers across the nation.

The time periods when these magazines arose also matter. Southern Exposure’s debut in year 1973 makes sense, when one keeps in mind this was also when the “Second Reconstruction” ended, according to a Newsweek article from that February.[1] The rise of the Oxford American, on the other hand, occasioned a year when the American South’s return to political supremacy on a national scale culminated with the election of an all-Southern ticket of Bill Clinton and Al Gore. While Southern Exposure was a place to argue for a new kind of South in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, Oxford American took stock of what came after two decades of Southern soul-searching about race and Southern culture.

Today, the rise of Scalawag makes sense in the same vein. A magazine begun by graduate students and scholars who focus on the American South, Scalawag has already made waves by presenting a South more in tune with the tradition of Southern Exposure or Oxford American¸ and less the assumed “Red State” America that drives most media coverage of the region. That isn’t to say Scalawag ignores the political and intellectual realities of the region; however, the magazine does provide some additional nuance about Southern politics and culture. Likewise, websites such as www.bittersoutherner.com provide a different version of the South from the mainstream assumptions about the region.

I have also seen this development of “little Southern magazines” up close, as colleagues of mine at the University of South Carolina have taken up the task of resurrecting Auntie Bellum, a 1970s era magazine about feminism in South Carolina. And considering the rise of several new magazines with a decidedly Left point of view—Jacobin, n+1, and The New Inquiry, among others—it will be important for future historians to keep in mind magazines based around regions of the United States. There they will find takes on the Confederate flag debate, Civil War memory, Hispanic immigration, and the Black Lives Matter campaign that all bring nuance to any understanding about the modern South. In short, thinking about the very recent intellectual history of the American South means reckoning with a still-vibrant print culture based around magazines and rapidly utilizing blogs as well to communicate new ideas about the ever-changing South.

[1] Peter Goldman, “Black America Now,” Newsweek, February 19, 1973, p. 29.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’ve never been to the American South, and all I gather about its character I get “second-hand; I feel like an outside observer, but I know novels would help, if I had time to read them these days. I notice that Southerners elect a lot of Republicans, but also that not everyone votes for them, and a lot of these must be white people. From all this I gather that the dominant unreflective conventional cultural resources of the non-intellectual white in-group is saturated with fear and hatred of the African-American community (but formerly including Jews and now including Latino and especially Muslim Americans) due mainly to their continuing inability to address the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, including the fact that there has never been adequate compensation for those evils that their forebears were responsible for, like holding the belief system that was the accepted foundation for thinking that slavery was something permissible. These ideas need to be renounced in an explicit and public way, seen to be renounced by a community who deny they are or were holding them, or even that they were wrong. I believe they would like to renounce them, could be even yearning for catharsis, but are unable for various reasons, including the fact that the plutocrat Republicans exploit this continuing schism to get their poll numbers.

I also notice that there seems to be a battle for the “soul” of Christianity these days, and a battle for the “soul” of Islam, sort of like the battle each of us has for our own soul as a person: which of the many “mes” inside us is the real “me”? We struggle for unification under the best fundamental ideas, of love, reciprocity, equality, because we don’t want a self riven by contradiction, but one that is unified with what Christians might call the “holy spirit”. It looks like the Southern soul is split, but I think that cultures should also feel free to battle for their real “soul”, to have a unified positive contribution that they can be proud of, and not be known for the shameful things they have done out of fear or ignorance, etc. That’s why we have the notion of compensation.

In any case, I’d been feeling depressed about Republicans and gun-nuts and so forth, and your post and your reference to these “little magazines”, which I did not know about and which I’m going to look at, has restored my optimism a bit. Thank you. (I’m not in the field of intellectual history, but have a constant interest in the history of ideas. I’m a total outsider here.)

Always glad to help! I think in many ways your post captures some of the problems here in the South–and in the 1970s, you had a regional “moment” where quite a few white Southerners, especially prominent politicians, renounced the past. Whether it was for voters or out of a genuine change is up for the debate, but the fact that it happened does mean something.

Your post is a gem of a read on the American South–more folks, hopefully, will read it and reflect upon it. Thanks for the important and kind words.