The internet is abuzz, once again, after the release of a Ta-Nehisi Coates essay in The Atlantic magazine. This one, tackling the history and current state of mass incarceration, has already sparked plenty of discussion online—from both supporters of his position and those either opposed to Coates’ “bleak” tone or his arguments. No surprise that another Coates essay, released so soon after his book about the African American experience in the twenty-first century, has generated so much discussion.

It would be a mistake, however, to read his essay in a vacuum. In fact, Coates’ piece is not the only important one to come out this month about African Americans and life in modern America. Randall Kennedy has another fascinating piece out in the October issue of Harper’s magazine. Meanwhile, an interesting roundtable discussion about the future of democracy has appeared in the September/October issue of Boston Review. What I’ll attempt to do today is link these three pieces together, as I believe they all have something to say about not just the African American experience, but the continued debate about American democracy that has taken new and stunning turns in the early twenty first century.

The Coates and Kennedy essays come out during an intriguing development in the historiography of American liberalism. Where once books about the 1960s tended to fault the excesses of liberalism and the New Left for conservative backlash—think Allen J. Matusow’s The Unraveling of America or Todd Gitlin’s The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage—now historians are taking a look at the limits of liberalism and asking, “Could they have gone further?” Or, on the other hand, some historians argue that liberalism reached its ideological and political limits in the mid-1960s, only going as far as was possible for an ideology inhibited by the same constraints that held back the United States as a whole—namely, racism, patriarchy, and other forms of discrimination. Books by Dan Geary (Beyond Civil Rights, who has also contributed an annotated version of the Moynihan Report on The Atlantic

website) and Ira Katznelson (Fear Itself), among many others, have asked readers and fellow scholars to think about the limits of twentieth century liberalism as a force for racial equality in American society. It is no surprise, during the Obama Administration, that such questions are being asked. A general wariness with grand political pronouncements about “hope” and “change,” coupled with renewed national debates about race relations, have no doubt led to a reappraisal of other moments of racial strife in America’s history.[1]

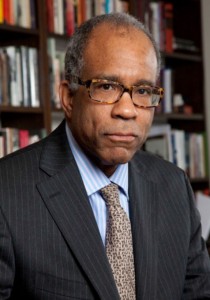

Randall Kennedy’s essay is a reminder that he is, for all intents and purposes, the dean of Black American liberalism. His essays—whether this one or last year’s “The Civil  Rights Act’s Unsung Victory” in the June 2014 issue of Harper’s, or his essays in The American Prospect (“The Civil Rights Movement and the Politics of Memory” in the Spring 2015 issue and “Black America’s Promised Land: Why I am Still a Racial Optimist” in the Fall 2014 issue) are not so much a rejection of the racial pessimism Ta-Nehisi Coates has been accused to writing about, as they are an affirmation of a mainstream liberal perspective on race relations. For Kennedy and others like him, race relations definitely need improving. But to say this without acknowledging how far the nation has come would be, for racial liberals, intentionally blinding oneself to the potential for still more reform in the future. His newest piece is an argument for “respectability politics,” arguing that they still have a place in today’s modern clashes over race. Kennedy, once again, uses the history of the Civil Rights Movement to make his argument: “Its association with esteemed figures and episodes in African-American history suggests that the politics of respectability warrants a more respectful hearing than it has recently received,” criticizing the attacks on respectability politics by Coates, Michael Eric Dyson, Brittney Cooper, and others.

Rights Act’s Unsung Victory” in the June 2014 issue of Harper’s, or his essays in The American Prospect (“The Civil Rights Movement and the Politics of Memory” in the Spring 2015 issue and “Black America’s Promised Land: Why I am Still a Racial Optimist” in the Fall 2014 issue) are not so much a rejection of the racial pessimism Ta-Nehisi Coates has been accused to writing about, as they are an affirmation of a mainstream liberal perspective on race relations. For Kennedy and others like him, race relations definitely need improving. But to say this without acknowledging how far the nation has come would be, for racial liberals, intentionally blinding oneself to the potential for still more reform in the future. His newest piece is an argument for “respectability politics,” arguing that they still have a place in today’s modern clashes over race. Kennedy, once again, uses the history of the Civil Rights Movement to make his argument: “Its association with esteemed figures and episodes in African-American history suggests that the politics of respectability warrants a more respectful hearing than it has recently received,” criticizing the attacks on respectability politics by Coates, Michael Eric Dyson, Brittney Cooper, and others.

Coates, meanwhile, has taken on a more radical position when it comes to race and American democracy. I am not sure if it is accurate to say that Coates’ works are pessimistic or, instead, carry within them a hard-nosed realism about America’s past and present. It is crucial to point out, of course, that his essays have sparked dialogue in a way that I cannot remember magazine pieces doing in a long time. Between his new piece on mass incarceration and his previous work on reparations, Coates has used his position at  The Atlantic to bring attention to the culpability of both liberals and conservatives in America’s racial ills. It is a mistake, however, to view Kennedy and Coates in the vacuum of “race relations” writing.

The Atlantic to bring attention to the culpability of both liberals and conservatives in America’s racial ills. It is a mistake, however, to view Kennedy and Coates in the vacuum of “race relations” writing.

The September/October issue of Boston Review includes a forum, headed by Ira Katznelson, which brings up questions about the present and future of representative democracy. Striking a chord between an alarmist position about the current condition of democracies with a nuanced understanding of the present and the past, Katznelson believes modern representative democracy is in need of serious reform. When intellectual historians, decades from now, study our modern era of printed (and online) debates about race and democracy, they will see a debate emerging that calls into the question the very legitimacy of democratic structure in the twenty-first century.

[1] We are, in fact, starting to see the same thing with Reconstruction. Eric Foner’s work, based off the earlier Black Reconstruction by W.E.B. Du Bois, has hung over Reconstruction historiography for nearly thirty years. With the passage of time, and new questions about Reconstruction being propelled by current debates about race and the American state, new works about the Reconstruction period are asking readers to also rethink that era in American history. Gregory Downs’ After Appomattox and Jim Downs’ Sick From Freedom, just to name two examples, offer new ways of thinking about that era in American history.

0