Early yesterday morning I came to understand the difference between the West and the Midwest. I had been driving all night: I made the mistake of attempting a cross-country trek the same weekend as the opening of the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in the Black Hills of South Dakota. So enormous is the gathering that every hotel room on I-80 between… well, I can only attest to the distance between Laramie, Wyoming and eastern Nebraska, for that is where I tried to stop for the night, a distance of more than 400 miles, although it was probably more expansive than that… was taken. There was simply no way I could stop for the night apart from a fugitive, 20-minute nap or two crumpled into my car seat in a gas station parking lot.

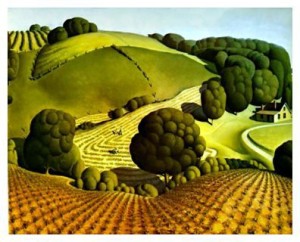

So I drove on. And at dawn some place in central Nebraska, I looked to my left over the fields on the other side of the road to find the sun timorously revealing a bank of waist-high, floury fog standing listlessly about the soybeans. There was such a frivolousness about this expenditure of moisture, much of which might burn away for the sake of a kind of stage effect seemingly for my benefit alone, that I felt a queasy shock of parsimony, and I realized that I had become, at least in part, a Westerner, worried about water and its misuses at an almost fundamental level. But then I looked further around and saw that my frugality was impertinent; I was no longer in Utah, and a little fog was not the same as someone running their sprinklers at noon. There can be droughts in this region, but moisture is not immediately and invisibly taxed from you at confiscatory rates the way it is in the arid West, where your very sweat disappears into the greedy air without a hint of acknowledgment of the taking.

There is a sort of knowledge that cannot be bought nor hypothesized nor extracted from texts that comes, I think, with driving over the vast breadth of the United States, over the “flyover country” in particular, but in general that comes with the driver’s eye view. Much has been written about the way that interstates have flattened, homogenized, alienated, etiolated, enervated, estranged the traveler’s relation to the country she is driving over, but there is still such an enormous difference between driving—being, at the very least, rolled with the wind that comes over the hills or through the windbreaks between the fields, forced into the shape of the road as it winds through outcroppings and arches over rivers—and flying, or assuming what a terrain is like based on second-hand testimony grubbed from our texts. I would like to suggest that historians, Americanists, should have that knowledge, as much as they can manage.

Cross-country travels are, even if they are made under superior circumstances to mine, grueling. The particular path I traveled traces many of the names that I first encountered in the computer game Oregon Trail, a cherished relic of my generation’s childhood. Fort Kearney, the Platte River, Laramie—I have enjoyed this revisiting of the hours in the school computer lab trying not to die of dysentery as I drive over this land, but it reminds me constantly of both how minor my discomforts are compared to the real travelers of the Oregon Trail and how much travel will always, to put it plainly, suck.

Furthermore, I know that my circumstances—living in Utah, but with my graduate school base and part of my family in New England and the Midwest—are unusual, and that I am fortunate to be able to have taken a number of cross-country trips to stay relatively close to those on the other side of the country. In other words, I know that saying that U.S. historians should have some experience traveling over the breadth of the nation is not asking little; it is asking something rather grand, something big. And it is perhaps presumptuous at my age and at my stage of career to think that I have some insight-bearing experience to cherish; that ought to be proved, after all, by turning it into something worthwhile.

But I offer this now as a stopgap, an encouragement that you will have other experiences like mine yesterday morning—though under more favorable, more comfortable, and less harrowing conditions. To the open road!

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, I ‘m so glad you posted this.

I am a big believer in road-trips, and in driving through “flyover country.” Once you drive through it, you see that it’s not something to fly over and ignore. Such lovely, bountiful land.

I took a road trip this summer to upstate NY and back, and I blessed Dwight Eisenhower’s name the whole way. The interstate highway system is a great modern marvel, and the countryside through which it flows is a marvel of a different kind. Nobody warned me that Ohio was so beautiful.

I too love road trips, so long as there are PLENTY of opportunities for stops, esp. when traveling with the children. …My lovely spouse thoroughly enjoys stopping for strange and weird roadside attractions (think of large balls of twine, etc.). – TL

In June 1993, I drove with my son Andrew, then 13, from our home in western PA to California, mostly via I 70, beyond where it stops in the desert of Utah. We arrived at Monterey Bay near dark at the end of the 6th day, able to go no farther.

Though Ike’s parallels of endless concrete are still there, no road takes us then. Space is no redemption for time.

Perhaps such a trip is part of the self-identification process for young American historians, implying the obligation to turn it into “something worthwhile.”

For me, there is surely the melancholy of viewing a lost object; but the take-away is that once was — and must be — enough: in part since much of the country is an almost geometrically empty space [especially if you include the sky] that has bound us with the misleading metaphor of an exceptional “open road.”