Recent news of both the passing of Julian Bond and the growth

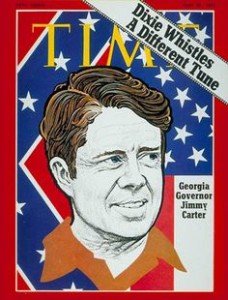

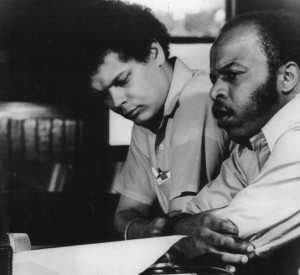

spread of former President Jimmy Carter’s cancer should be an occasion to think about the kind of legacies built by both men. Bond and Carter embodied both a certain era of American history—the Civil Rights Movement and the national reckoning with its legacy—and a certain region of the United States, the American South. The fact that the two men had national prominence at the same time, and just happened to occupy positions of authority within the Democratic Party, is also important. In essence, Bond and Carter were, I would argue, the face of a certain type of Southern identity that attempted (not always successfully) to forge a “New South” identity in the 1970s and beyond.

I have written about this “New South” idea elsewhere. For a quick refresher, keep this in mind: the American South was irrevocably changed after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both Bond and Carter had a hand in the initial upheaval of the Civil Rights era. Of course, Bond’s contributions to the Civil Rights Movement are well-known, as are the ties of his family to the long history of black self-determination in the United States. Jimmy Carter’s own reckoning with civil rights was a bit more complicated, due to his position as a moderate within the segregationist Georgia Democratic Party of the 1960s. Carter’s own runs for governor’s seat in Georgia  in 1966 and 1970 point to the political tightrope

in 1966 and 1970 point to the political tightrope

Carter had to walk in order to ultimately win. The 1970 campaign, in particular, soured many Black voters on former state senator Carter, whose victory in the Democratic primary and the general election was based on appealing to white southerners who still weren’t sure of what to make of the growing political and economic strength of African Americans in the South.

Nonetheless, Carter’s 1971 inaugural speech, where he proclaimed an end to racism as the center of Georgia and, by extension, Southern culture and politics, was a watershed moment in the history of the American South and the United States. As intellectual historians, we would do well to keep in mind how Southerners have always wrestled with identity. This should not be seen as a flimsy, nebulous phrase that sounds sophisticated but says very little of use. Instead, the idea of Southern identity is one that should be questioned and, at the same time, taken seriously by historians concerned with the American past. The lives and contributions of Bond and Carter both point to the importance of understand how dissent from mainstream Southern intellectual thought—whether only moderately so in the case of Carter, or drastically in the case of Bond—can mean the creation of new ideas about what it means to be a Southerner.

Intellectual historians of the early twenty first century will, in time, have to reckon with a similar debate about Southern identity taking place in the here and now. Magazines such as Oxford American, Scalawag, and websites such as The Bitter Southerner and Battle Flag have all argued for a new and updated definition of “Southern” and “Southerner.” The 1970s experienced a similar period of ferment in the public sphere, as several magazines grew out of the post-Civil Rights debate over the future of the South. Magazines such as Southern Exposure presented a more tolerant, liberal south willing to confront its past (although not, by any means, proclaiming that to be the only South still in existence). At the same time, mainstream publications such as Time and Newsweek approvingly mentioned changes in the South’s culture and politics during the era.

Conceptions of the South matter. Throughout American history, the South has been perceived as different from the rest of the nation. While this idea of “Southern exceptionalism” has come under considerable scrutiny over the last ten years (and, indeed, for many African American intellectuals and activists, has been debated for much, much longer) we continue to debate it as part of questions about American ideas, American politics, and American culture. Recent debates about the Confederate flag and Confederate memorials point to how this debate has entered a new, and more urgent, phase. At this moment we are experiencing a drastic upheaval in once-bedrock principles of Southern civil religion. In order to understand how we got here, however, the importance of Julian Bond and Jimmy Carter, among other prominent Southerners, is something intellectual historians will have to grapple with for decades to come.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Nice post, Robert. The editor in me would prefer “spread” rather than “growth” of Carter’s cancer, but that’s small potatoes to the overall strengths of your arguments that we take ideas of southern identity and its evolution seriously.

Thanks, I greatly appreciate that! And you’re right–that would be a better word choice. I’ll make a quick correction.