The last few weeks for me have been occupied by creating a syllabus for a course titled “The Contemporary South.” It is a dream opportunity for me, and one that I hope only further heightens my excitement about teaching in the classroom. Today I wish to toss around ideas I have had for what I will call “dream intellectual history courses”—in other words, the kind of classes I want to teach down the road once I have my Ph.D. in hand. These are class ideas I’d have for graduate seminars, although they could also be adapted for upper-division history courses for undergraduates. What follows are five of my ideas. I hope to see yours in the comments section!

Paul Robeson and the American Century—I tossed this idea around with a few colleagues  of mine (one a 20th century Africa historian and the other Reconstruction and Gilded Age era African American historian) of one day doing a course on Paul Robeson and American intellectual and cultural history. It would trace not just his trajectory in American culture, but also use Robeson as a lens into wider African American and Left movements from the 1920s through the early 1970s. Plus, I think any opportunity to talk Paul Robeson in a class should be taken with all haste.

of mine (one a 20th century Africa historian and the other Reconstruction and Gilded Age era African American historian) of one day doing a course on Paul Robeson and American intellectual and cultural history. It would trace not just his trajectory in American culture, but also use Robeson as a lens into wider African American and Left movements from the 1920s through the early 1970s. Plus, I think any opportunity to talk Paul Robeson in a class should be taken with all haste.

The New South, 1960-2000—The title is probably self-explanatory, but nonetheless it’s a course I would love to teach someday. In relates back to the “Contemporary South” course, which is an interdisciplinary course housed in Southern Studies designed to give students exposure to scholarship about the South from 1970 until the present. While “The New South” would be a history course, I would focus on the intellectual history of the region—as well as how the intellectual history of the country relates back to the South during that time period.

Sports and American History—the intersection between sport and intellectual history is one that we should think more about. We have seen posts here at S-USIH that have examined this question from a number of angles. How intellectuals have viewed sport—and how sport has become a key component of American life—would be the foundation for this course.

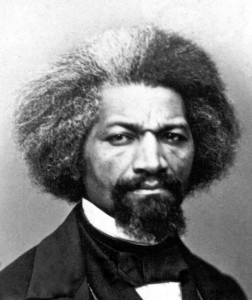

Black American Intellectual History—this one would be a favorite of mine as well. A field that still has plenty of places left to go, Black American Intellectual History would offer new ways of viewing American intellectual history. Inspired by W.E.B. Dubois, Harold Cruse, Anna Julia Cooper, Angela Davis, and a wide variety of others, this course would be a survey of a vibrant intellectual history.

Towards an Intellectual History of the Western Hemisphere—this one would be the most ambitious idea. Thinking about the importance of Latino/a Intellectual History—seen on this blog in both a recent roundtable and the winner of the S-USIH book award

—is going to become crucial for U.S. intellectual historians as time goes on. And we can’t forget our friends up in Canada, either. Such a course would ask students to consider how intellectuals across the Western Hemisphere interact with one another. I am not sure when the class would start, although the Age of Revolutions seems as good a place to start as any.

So those are my dream classes. By no means comprehensive, I hope to start a conversation here about the kinds of classes you’d like to teach if you could—or better yet, classes you have taught in the past and what worked about them.

Also, I heartily recommend checking out the last week in U.S. Intellectual History blogging. We had another wonderful entry in what’s becoming a series of meditations on Between the World and Me; the very look of being an academic; the work behind cultural creation; two fantastic interventions in the debate over Confederate memorials; thoughts on settler colonialism as an idea; Common Core and the Right

; and finally, morality and foreign policy. All wonderful posts. And a special shout-out for the latest #Blktwitterstorians discussion, this time about Black Power. It will be archived and storified soon, but until then, check out

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Awesomeness! Having been fascinated by the debates and different points of view on Pan-Africanism and Communism in the AAIHS blog, I would take the Robeson course in a heart beat. I wonder if a Black American Intellectual History course should include black voices from the Latino canon and politics of Afro-Latinidad–I think in particular of Arturo Schomburg, but there are some other significant figures; Antonio López’s Unbecoming Blackness focuses on the Cuban genealogy.

Last but not least, I also dream about a hemispheric course as the one you outline–I would frame it around empire and revolution, particularly through the politics of US imperialism and its reception across the Americas. Such a framework would allow a broad perspective, enabling the study of Latina/o history, Latin American alliances and resistance against the US, and how ideas of the “American self” were fashioned in opposition to the Latin American / Caribbean other, in dialogue with key events such as the US invasion of Mexico, Cuba, and Haiti, its interventions against “leftist” governments during the Cold War, and the foundation of Communist Cuba. I would sadly have to exclude Canada from the mix, perhaps you or somebody else can suggest how Canada can be included in a dialogue from a hemispheric perspective in such a class (maybe in a class focused on migration and displacement? Focused particularly on the Caribbean, taking into account the Afro-Caribbean cultures in Canada?).

Ah, an interesting way to link Canada with the rest of the hemisphere would be to teach a course on hemispheric indigeneity, focusing on native ethnicities across the Americas. A very ambitious undertaking, but it would be a lovely dream course…

I loved your points here–I was hoping you would chime in. I mentioned Canada mainly because it seems they often get ignored in this sort of historiography–I know that some of the Black Power and Civil Rights historiography is just starting to take aim at the relationship between activists in Canada and the USA.

And I wholeheartedly agree that any African American intellectual history course would have to include an Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino/a element! No other way to do it.

The Paul Robeson course sounds like a very good idea. I think a biographical lens is often an inviting way (for readers and also probably for students) to “get into” a whole era. With respect to the 20th-century U.S., one example that comes to mind is R. Steel’s excellent Walter Lippmann and the American Century. And studies of figures such as Robert Oppenheimer or Acheson or Kennan have been used as windows onto large chunks of the Cold War. I’m sure taking Robeson would prove equally illuminating, albeit of different topics and from a different set of angles.

And as far as notable African-Americans are concerned, Ralph Bunche or Andrew Young — esp. Bunche — might be good candidates for constructing a course around, at least if one wanted an international dimension. (These two just come to mind given my particular interests.)

Great ideas! Both Bunche and Young would offer good bios through which to view America and the World.

Robert: what a cool idea for a post!

Here are some ideas I had. My guiding impulse is the idea that a good grad seminar should allow every student so compelled to produce some publishable original writing without having to travel to an archive:

1) The Epistemological Left: borrowing Novick’s term for post-60s radical thought, a class that reads postmodern and poststructuralism in the US from a variety of perspectives (sociology of knowledge, social history of Left and academia, culture wars and Sokelism, etc.) What would be cool would be to combine primary readings of Judith Butler, Critical Race Theory, and the American reception of Derrida, Deleuze, Lacan, Foucault, French feminism, etc with secondary sources.

2) American Capitalism and Its Critics (in Primary Documents): An all-primary doc historical survey from 1870-1970, more or less, including at least one novel per week, and lots of materials from the Left little magazines and African American press.

3) The State and Economic Knowledge and Counter-Knowledge: also a primary-doc-intensive class, reading JB Clark, Veblen, Patten, et al, as well as laborist, lefist, and other radical writings from Henry George to Baran and Sweezy to Robert Brenner and David Harvey; with relevant secondary texts like Furner and Supple, Thomas Stapleford, Sklar, Sklansky, Mary Morgan, M. Poovey, P. Mirowski, G. Krippner.

4) The Many Lives of Property Law: This could be a surprisingly rich class, I think, and would include Marxist, feminist, and African American and anti-racist texts of property, as well as classics from John Commons to Berle and Means, Hayek and Morris Cohen, Richard Epstein, Cheryl Harris, and Patricia Williams, as well as a section on intellectual property. Primary docs here would center heavily on court cases and intellectual history of debates re Prop 13, “takings,” “tort reform,” property rights in whiteness, and corporate personhood.

5) Weirdos, Oddballs, Radicals: Eccentricity and the Secret History of the Left

Don’t know what this would be, but I would want to take this class! I feel like we don’t talk enough about the non-joiners, the outsiders, those heroically faithful to their own eccentric self-fashioning. I guess a big part of this kind of class would be figuring out, collectively, if this is indeed a productive category for intellectual history, and if so, how to theorize and situate research so that it does not replicate normative structures of “inside” and “outside”?

These are wonderful class ideas. I do like, especially, your idea of primary-source based grad courses. And I also enjoy the ways in which your classes are changing the way we think about intellectual history. Certainly something we need more of whenever possible.

I’ve had fantasies about a course exploring counter cultures in the Americas, covering pirates, maroon colonies, pan-Indian movements, lgbt communities, pan-African movements in the Americas, and perhaps some stuff on modern music-oriented counter-cultures from Jazz to, Punk, to Hiphop. I guess it’s more cultural history but it certainly converges to a large extent with Intellectual history. The biggest problem for me is that I know so little about so many of these, but I’d love to devote a year to develop this course.

I’d definitely be game for courses based around one of these ideas. I know I’ve always wanted to explore more about the relationship between Jazz and U.S. cultural and international history in the 20th century.

And Hip-Hop and Intellectual/Cultural History? That’s definitely a course to consider, heh. I’ve had to think about this developing my Contemporary South course, which will focus a bit on country and hip hop musical forms since 1970.

Canadianist here (eep!) with some small observations in keeping with Canada’s small historiographical stature.

Canada can actually contribute to a broader, revisionary, conceptualization of the age of revolutions in a number of ways. The North American (more broadly the Atlantic) trajectory of political ideology—the hypothetical ‘debate’ between toryism, republicanism, and liberalism—acquires a different coloration when you include Canada’s either more ‘conservative’ or more ‘liberal’ response to 1774 (this being the subject of a big and inconclusive debate). Following out from this issue, the trajectory of ‘modern’ political development with the implicit assumption that ‘freedom’ inheres in the foundation of the ‘nation-state’ can itself be problematized. The American Revolution elicited an often profound antagonism from ‘loyalists’ and ‘minorities’ who vastly preferred the clientism and heterogeneity of the British Empire to the prospect of a homogenous and unitary anglo-american republic. These included: poorly integrated semi-feudal frontier communities of Germans, French, Scottish; the many aboriginal tribes with whom the British had concluded formal political arrangements; reluctant (recently conquered) French Canadian habitants; and perhaps most notably, the so-called ‘black loyalists’ (often escaped slaves) who provided military service in exchange for permanent British citizenship. This motley collection of outsiders, with the success of the American Revolution, would become the ‘losers of North American history’ (as I think Bailyn put it?) and the basis of the Canadian state.

If there are possibilities there are also very significant limitations to the categorical distinction this might begin to imply: that Canada was a pluralistic and multicultural ‘exception’ to the sweep of the universal Anglo-American ‘liberal order’—with its implicit ‘ontology’ of white male rationality and all the attendant political implications. This has nonethelss become a powerful English Canadian myth. Nonetheless: by the mid-nineteenth century, the heterogeneous political formation of ‘British North America’ would increasingly give way to a liberal English Canadian ‘fragment’ in a manner broadly in keeping with the recurrent pattern of nineteenth century English settler colonialism. The aggregation of Canadian, Caribbean, and Latin American historical experiences, through scholars like Wim Klooster and David Armitage, can facilitate a different, but similarly dispiriting conclusion: that the ‘Age of Revolutions’ were dominated by (elite) issues of nascent state sovereignty, the revolutionary narrative of the democratic will of the people being frequently a subsequent invention or development. Other relevant scholars would include: Jerry Bannister, Keith Mason, Maya Jasanoff, and Richard White. I am not, however, an Atlanticist, so there might be more to say here.

To speak to the ‘minoritarian’ theme more generally (perhaps superficially): the Black Canadian historical tradition is profoundly limited and overshadowed by the United States; I wish I could speak more to their experiences. Aboriginal Canadian historiography, though it has not (to my knowledge) contributed to a self-consciously hemispheric scholarship, or a distinctively Canadian set of historical problems, has recently gained some strength by tapping into post-colonial thinking with the effect of framing, perhaps dramatizing, European-Aboriginal Canadian experience through the paradigmatic conflict between ‘western’ and ‘subaltern’ ontologies—at the expense, in my opinion, of often extremely complicated historical issues centering around the comparative distinctiveness of Canadian Indian Policy, but perhaps to good effect.

Thanks so much for this! I was hoping a Canadian specialist would chime in, and you’ve given us all a great deal to think about. I definitely want to digest these ideas some more and think about them in the broader context of both the Atlantic World and the Western Hemisphere.