A gallery located in the campus center at IUPUI has recently become home to an exhibit on the work of Ray Bradbury. Among the items are copies of his most famous books (including Fahrenheit 451), screenplays (including the one he wrote for John Huston’s Moby Dick), posters of movies made from his original stories, and a treasure trove of personal material from scrapbooks he kept as a teenager to the desk he used almost until the day he died. Jon Eller, Bradbury’s most thorough and capable biographer, has assembled these pieces from the collection he maintains as director of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies

A gallery located in the campus center at IUPUI has recently become home to an exhibit on the work of Ray Bradbury. Among the items are copies of his most famous books (including Fahrenheit 451), screenplays (including the one he wrote for John Huston’s Moby Dick), posters of movies made from his original stories, and a treasure trove of personal material from scrapbooks he kept as a teenager to the desk he used almost until the day he died. Jon Eller, Bradbury’s most thorough and capable biographer, has assembled these pieces from the collection he maintains as director of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies

at IUPUI. The physical centerpiece of that collection and of the exhibit is Bradbury’s desk, arranged to reflect roughly what Bradbury saw when he sat down to write. Playing upon one of Robin Marie’s recent post on the aesthetics of scholarship, I suppose this desk might reflect an aesthetic of Bradbury’s mind. The fact that Eller has kept this desk as a testament to Bradbury’s work suggests his intention to link the physical environment in which Bradbury wrote to the work that millions of people have come to know. That link is rich with potential for analysis and artful narrative. This post is a plea to discuss how to create a material exhibit about a person’s mind.

The desk has Bradbury’s IBM Wheelwriter typewriter as its centerpiece. It was through this machine, Jon Eller explains, that Bradbury wrestled with his work–contending with ideas, as Bradbury liked to say, that were like “bulldogs,” once they got dug into him they wouldn’t let go. Eller told me that sometimes Bradbury would be so taken with (bitten by?) an idea, that he would write blindly with the lights completely off so his wife could sleep.

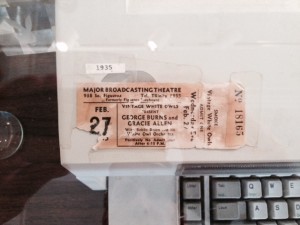

Pasted to the typewriter was a ticket to a 27 February 1935 Vintage White Owls radio show with George Burns and Gracie Allen. Eller pointed out that this show was, for its time, among the very few that broadcast before a live audience. Bradbury was such an admirer of Burns and Allen that he not only attended the show, he pitched ideas for it as well.

Pasted to the typewriter was a ticket to a 27 February 1935 Vintage White Owls radio show with George Burns and Gracie Allen. Eller pointed out that this show was, for its time, among the very few that broadcast before a live audience. Bradbury was such an admirer of Burns and Allen that he not only attended the show, he pitched ideas for it as well.

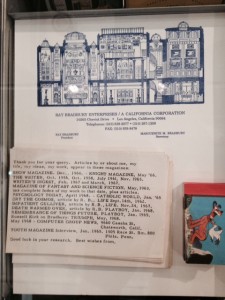

The letterhead Bradbury kept is especially intriguing. He used a black and white illustration of the Soane Museum in London as the image to represent him in his correspondence. I admit I did not know about the Soane Museum until Eller filled me in. But seeing it as a kind of bizarro British Museum seems to fit Bradbuy’s personality and his intellectual aesthetic. The collection has no great theme other than curiosity–a characteristic that Bradbury certainly embraced to describe himself.

The gallery exhibition and this desk in particular, has me thinking much more deliberately than I have in the past about the woeful academic gap that persists between historians who portray their work in different ways, or, in other words, between public historians and other historians. Of course, we are all historians but the world I so often inhabit has not done a great deal to provide the skills or even the discussion of what to do with physical objects. While I have indeed walked through countless museums and am well aware of the professional organizations that serve the communities within public history, as well as state and local historical societies, I want to know what more we can do to create conversations about physical interpretations of the mind.

Frankly, I am taken by this exhibit not just because it is filled with cool stuff but because it prompted me to think more deliberately about how to characterize Bradbury the person, the writer, the observer of twentieth century American culture. It made me think about what Gilbert Seldes analyzed in his landmark collection, The Seven Lively Arts, originally published in 1924, because it was the culture Seldes observed that inspired generations of writers, including Bradbury. Seldes concluded: “The simple practitioners and simple admirers of the lively arts being uncorrupted by the bogus [,] preserve a sure instinct for what is artistic in America.” (295) Much the same can be said for Bradbury’s collection of items that reflected his interests and, more to the point, for the gallery exhibit that gives us access to a lively mind.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

at a writing seminar i attended once upon a time in a land far far away, we writers were told to decorate or offices, cubicles, etc., with things that made us feel comfortable. company or institutional decor be damned.

Ray: I don’t know if we need museums to show us what tools we use to express our minds as much as need exhibits that portray, somehow and someway, what inspire intellectuals to do creative and critical thinking. That’s what I like about your post—you hint around things that inspired Bradbury, symbols that opened his mind. So the issue of your penultimate paragraph is about how public history handles intellectual history. Perhaps there aren’t enough museums out there, dealing with intellectuals, that exhibit the material things that actively stimulated the intellectual imagination? What is it that makes us want to be critical thinkers? What drives the imagination? How much does the material do that, or is it a felt ethic, transposed to creative narrative? – TL