Since I started here at the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians’ blog in the summer of 2013 as a guest poster, I have come back time again to questions of the race and the South in the American mind. Even then, though, I had no expectation that such talk would eventually lead to analyzing the deaths of nine churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, or a now-year long “Black Lives Matter” campaign. Closer to home for me, Columbia, South Carolina just experienced a Ku Klux Klan rally on July 18 (which, coincidentally, was the 152nd anniversary of the African American 54th Massachusetts’ Regiment charge on Fort Wagner). Held to uphold the “heritage” idea behind flying the Confederate flag, the group that converged on the Statehouse—outnumbered by counter-protestors, including the African American group Black Educators for Justice, which held their own rally earlier that day—the mixed group of Klansmen and women, along with Neo-Nazis, needed police protection to ensure their own security. No doubt the Klan has seen better days, especially in the South.

With that said, it is imperative for historians (especially those like myself who examine the post-Civil Rights era in the American South) to wrestle with what the Klan has come to symbolize since the 1960s. To most Americans, it is an unfortunate reminder of the openly racist society that existed, North and South, for decades. For African Americans, it is the most virulent symbol of the need to remain vigilant against racism in American society. And for most Southerners, white and black, the KKK is an embarrassment. Despite the spread of the Klan during the twentieth century across the nation, the Klan is still seen in many ways as a manifestation of the worst of the South’s racism and intolerance. So it is no surprise that, whenever the Klan attempts to make its presence felt in a Southern town or city, for the most part they receive nothing but ridicule from the local citizens or—arguably, even worse—complete ignorance of their presence in town. Yet back in the late 1970s, as the aftermath of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements faded further into historical memory, a resurgence of the Klan across the South alarmed many on the American Left.

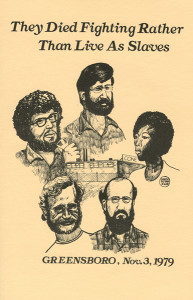

Reading both books and magazines of the late 1970s, one gets a sense that Southerners were attempting to come to terms with what it meant to be a Southerner after decades of being seen as an “Exceptional” region within the United States. But by 1979,  events in the South threatened to bring back old, and painful, memories of the South. In November of that year, Klansmen and Neo-Nazis fired on members of the Communist Workers’ Party (CWP) at a rally in Greensboro, North Carolina. Five members of the CWP were dead, and all the shots fired that day were discharged from weapons owned by the Klan.

events in the South threatened to bring back old, and painful, memories of the South. In November of that year, Klansmen and Neo-Nazis fired on members of the Communist Workers’ Party (CWP) at a rally in Greensboro, North Carolina. Five members of the CWP were dead, and all the shots fired that day were discharged from weapons owned by the Klan.

Reaction from the Left was swift. In December 1979, the National Anti-Klan Network held a rally in Atlanta. A speech given by Anne Braden, a tireless campaigner for civil rights and broader anti-racist movements (and a white Southerner) was included in the first volume of the 1980 edition of Freedomways, the venerable journal of the African American Left. As always, context matters. And here Braden argued—in an argument that would have echoes elsewhere across the Left—that the nation was experiencing a moment of social and economic turmoil that threatened to give the Klan more power and more recruits. She believed the United States circa 1979 to be a nation on the precipice of potential disaster, and argued that the KKK had the potential for a third period of growth similar to that of the late 1860s or 1920s. “The point is that both of these times of great Klan growth—the post-Civil War period and the 1920s—were periods when great numbers of people were feeling overwhelmed by problems in their lives and their society that they saw no answers for,” she argued.[1]

She went a step further, to paint an even darker picture of the nation. Braden invoked nothing less than the growing “carceral state,” arguing, “That’s why those in power are now building 500 new prisons and prison units across the country, at a cost of from $35,000 to $50,000 per cell.” This shouldn’t be a shocking statement for someone speaking in 1979—already, critiques of the prison-industrial complex were being made by Angela Davis and by members of the Black Panther Party. Nonetheless, with today’s intersection of discussion about “Black Lives Matter” with debate about the growth of the carceral state, it gives one pause to consider that Braden connected the growth of prisons to the resurgence of the Klan in 1979.

Southern Exposure, a magazine by and about Progressive Southerners, devoted an entire issue to the resurgence of the KKK. Driven by the Greensboro Massacre, the Summer 1980 issue (titled “Mark of the Beast”) detailed the Klan’s history, their present resurgence, and the future of the organization in the South. However, along with the grim news of Greensboro, Southern Exposure writer Vanessa Gallman pointed out that in Dallas, Texas, on the same day, the KKK was driven out of town by angered onlookers. “The Dallas incident is only one recent example of Southern communities reacting aggressively to the Klan. The “ignore them and they’ll go away” attitude is increasingly being rejected,” she wrote, explaining a new drive across the South to counter the Klan wherever they appeared.[2] In many ways this same fervor helped to drive the Greensboro Massacre—residents were worried when the CWP called out the KKK and demanded a confrontation.

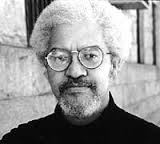

Across the Left, activists, journalists, and scholars alike expressed alarm over a Klan resurgence in the 1970s. In his important work How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America, historian Manning Marable argued that the Klan’s attack in Greensboro was but part of a larger right-wing resurgence in America. It was part of three “green lights” that signaled an upswing in racially charged violence across the nation, compared by Marable to the aftermath of the Bakke decision in 1978 (which weakened affirmative action) and the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.[3] For Marable, the very fabric of  American democracy was in peril. He brought these three factors together under the umbrella of the Ronald Reagan campaign: “Reagan’s campaign was based upon the same putrid ideology of racism, limited Federal government, sexism, anticommunism and states’ rights that catapulted George Wallace to national prominence in the 1960s.”[4]

American democracy was in peril. He brought these three factors together under the umbrella of the Ronald Reagan campaign: “Reagan’s campaign was based upon the same putrid ideology of racism, limited Federal government, sexism, anticommunism and states’ rights that catapulted George Wallace to national prominence in the 1960s.”[4]

It is important to note that all these voices—Braden, the writers at Southern Exposure, and Manning Marable—all brought different points of view to the Klan resurgence issue. Anne Braden’s experience as a white Southerner campaigning against racism for decades colored her world view in a different manner than the mostly young staff at Southern Exposure, which was attempting to show the South moving in a new direction. And they both differed wildly from Manning Marable, who at the time maintained staunchly Socialist credentials while also writing and working in the vein of the classic African American “scholar-activist.” Leave no doubt, though: people across the American Left worried about a resurgent Klan in 1979-1980. For them it was a dangerous symptom of a larger illness—America’s rightward drift in the late 1970s. The United States was no longer a “nation of sadness” as Michael Harrington argued in 1974. It had become, by 1979, a dangerous and confused nation to many on the Left. As intellectual historians, we can examine the Klan as a bogeyman for the Left, symptomatic of larger problems Left intellectuals perceived and worried about in the late 1970s.

[1] Anne Braden, “The Ku Klux Klan Mentality—a Threat in the 1980s,” Freedomways, Volume 20, Number 1, 1980, pp. 7-14, quote on pg. 8.

[2] Vanessa Gallman, “Klan Confrontations,” Southern Exposure, Volume 8, Number 2, Summer 1980, p. 76.

[3] Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America (Boston: South End Press, 2000 [1983]) p. 243-245.

[4] Marable, 244.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

In the early 80s you find northern leftists worrying about an upsurge of Klan activity in urban and periurban centers undergoing rapid industrial decline. At least, lots of this around Pittsburgh. I can’t vouch for the seriousness of the threat, but the concern on the left was nationwide (in large part due to Greensboro, no doubt).

Great point–and I can’t say I’m surprised. And the figures writing here are also thinking about this in a national context–but, and this is especially important for the folks writing at *Southern Exposure*, the greater ideological and political concern was how far the South had come since the heyday of the Civil Rights Movement. In essence, both the resurgence of–and backlash against–the KKK symbolized both the best and worst of the South.

And that concern in the early 1980s is something I’m also keeping an eye out for in my research.

Robert, Great post, and awesome material! I’m wondering about how the Southern Poverty Law Center might fit into this narrative. I would imagine they were involved in much of the response to Greensboro, but to what extent do you see some of the other anti-Klan activists whom you mention using their data or reports, or cooperating with them to track the Klan’s activities? And do you see SPLC’s presence in Montgomery as part of this 70s moment of trying to figure out Southern identity after the high point of the Civil Rights Movement?

Sorry–those questions came out a little more specific than I initially had in mind, but I really am just interested in hearing you talk about the SPLC in all of this.

The SPLC is definitely involved in this era. 1979 was the last year of Julian Bond’s presidency, and they were really gearing up their anti-Klan efforts by this point.

I am not sure about how much activists are using SPLC information, but I know that it’s definitely part of a larger network of information being assembled across the South. But I do agree with you that the SPLC is part of this “re-imagining” of Southern identity in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the themes of my dissertation (and a book chapter I am working on for a separate pub) gets at the importance of the SPLC as a standard-bearer, along with publications like *Southern Exposure*, of a different and more tolerant South.

Thanks for your questions. I have been toying with a post on the SPLC and intellectual history, so I think you’ve spurred me to do one quite soon!

I had no idea this happened. I bet I’m not the only one. This has been completely blotted out of the historical memory. Well, not completely, but mostly. A couple of points:

1) “Five members of the CWP were dead, and all the shots fired that day were discharged from weapons owned by the Klan.”

I dislike this sentence. It’s too impersonal. Especially description of the guns as “owned by the Klan.” Does that mean the Klan members weren’t holding them when they were fired? I know you don’t mean to convey that impression, but it can be read that way. Also, there’s a disconnect between the five dead people and the shots being fired. Five people are dead, and shots were fired. But there’s no direct link between those two events. I presume the CWP people were shot and killed by the Klansmen. Can you say that? Or is that something that can’t be directly confirmed? I hate to be nitpicky, but this sentence struck me as clouding the issue.

2) Your description of the activists’ reaction to the shooting reminded me of something we were discussing on Twitter the other day. Namely, how there’s a sense now that the window might be closing for African-American political activism. That promotes a sense of urgency on the one hand and desperation on the other. It seems to me Marable, Braden, et al. perceived themselves to be in a similar situation in 1979. There’s so much work yet to be done, but the shadow looms. What’s the shadow this time?

Thanks for the comments as always. I do apologize for that odd phrasing–I meant to clean it up, but essentially the people accused of the attack were never convicted. So, in essence, it’s plain to almost everyone that Klansmen killed the protestors, in broad daylight, and the incident was caught on film. But by the law, only civil suits years later brought about any sort of “justice” for the five protestors killed.

And to your second point, there’s definitely some interesting parallels between now and 1979. One that I did not bring up, but was on my mind as I wrote this post, was the 1980 Miami riot. It was a startling reminder of the same racial issues that Marable and Braden were concerned about. As for what the shadow is this time, I am not sure. But as historians, we know better than to predict the future–or even understand all the lessons of the (recent) past.

“But as historians, we know better than to predict the future–or even understand all the lessons of the (recent) past.”

Darn tootin’.

Great post Robert–as always!

Two exciting points of resonance: 1. organizers from Critical Resistance were housed by Anne Braden as they traveled throughout the South to build up support for the CR South conference in 2003 (though, it might have been for CR East in 2001–I’m not 100% certain). And Angela Davis and Braden went very far back, in addition to both being leading members of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression. All of which is to say, Braden and the contemporary anti-imprisonment movement are thoroughly connected.

2. Also, the current project of the amazing Rebecca Hill (*Men, Mobs, and Law*) is on histories of anti-Klan and anti-fascist organizing. It’s going to be great.

Thanks again for this post!