(Note: this is a guest post from friend-of-the-blog Kit Smemo, who is a Ph.D. candidate at UC Santa Barbara, completing a dissertation on liberal Republicans and twentieth century labor politics).

Introduction: Wartime Migration and the “Arsenal of Democracy”

Less than a year after race riots tore through Detroit, the NAACP magazine The Crisis famously placed the Motor City at the center of the “increasing friction between the two old American traditions, one of which is essentially liberal and democratic and the other patently reactionary and anti-democratic.”[1]

Thanks to a host of path-breaking histories we know well how that friction exploded on the streets and shop floors of World War Two Era Detroit. For civil rights activists and intellectuals at the time, the bloody struggle between those “two old American traditions” spoke volumes about the past and future of modern black politics. At the heart of this battle of ideas was the radiating impact of what Thomas Sugrue calls the “proletarian turn” in the struggle for racial equality.[2]

Here, we consider two political thinkers—both writing in the mid-1940s and both working in roughly the same racial liberal milieu—who drew sharply different conclusions about how to conceptualize this “proletarian turn.”

In the summer of 1944, Deton J. Brooks, then national editor of the Chicago Defender

, penned a series of articles describing a confident new mood in the black communities of the North. In anticipation of the upcoming general election, Brooks specifically promoted the idea of a black “balance of power” able to decide close elections in such vital electoral battlegrounds as Michigan. Brooks conjured the image of staunchly independent black electorate in order to leverage concessions on civil rights from white politicians anxious about the polls. But his project could not help but reveal the limits to the integration of the black working class into a New Deal coalition that took as paradigmatic a certain narrative of the integration of European immigrants into American civic life.

That same year, Swedish social scientist and social democrat Gunnar Myrdal published his massive study An American Dilemma. Though Myrdal and his collaborators gave relatively scant attention to the contemporary urban North, the book’s passages on African American politics in places like Detroit dismiss outright the sorts of concerns that preoccupied Brooks. According to Myrdal, black refugees from the Jim Crow South would follow a path of political modernization travelled first by refugees from Southern and Eastern European feudalism. The coming of the New Deal only promised to speed the political maturation of the black electorate—a process that would invariably lead black voters to fall into familiar patterns set first by white voters.

Both Brooks and Myrdal focused on the right to vote, and thus largely dealt with politics in its most formal dimension. While social historians are correct to note that a narrow focus on the polls obscures from view much that is crucial to politics, we should not take their critique as a cue to abandon interest in electioneering altogether. Voting and forecasting of the behavior of coalitions in major elections drove much of the intellectual history of the post-“proletarian turn” civil rights movement. The acquisition of voting rights by the formerly disenfranchised African American worker in the World War Two Era stimulated passionate debate. “The ballot,” historian and civil rights activist Lawrence Reddick declared in 1944, “gives the northern Negro a powerful weapon which his southern brother does not yet possess.”[3] We have not yet fully appreciated the gravity of Reddick’s observation.

The World War Two made Detroit a newly important hub of African American political life. For writers such as Deton Brooks, it also became representative of all the political opportunities and perils facing northern black labor migrants at mid-century. In June 1944, Brooks sketched a brief history of black voting in Detroit.

In Brooks’s telling, before the Depression, Henry Ford’s competitive wages brought thousands of black labor migrants up from the South to work at Ford Motors’ sprawling River Rouge plant. African American workers, in turn, loyally cast their ballots for the GOP—the party of Lincoln as well as the automakers. In the depths of the Depression, however, the material security provided by the New Deal’s relief and recovery programs handily trumped Ford’s paternalism. In a stunning repudiation of the GOP, black Detroiters helped elect crusading New Dealer Frank Murphy governor in 1932. Four years later, they overwhelmingly backed President Roosevelt.[4]

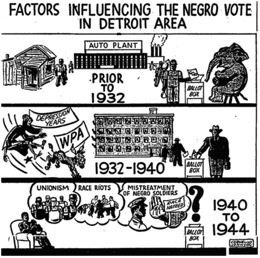

Fig. 1. The Chicago Defender’s illustrated history of black voting in Detroit—as well as its uncertain future.

Chicago Defender, June 3, 1944, p. 4.

But Brooks also stressed that proletarianized blacks could not be so easily assimilated into the working-class ranks of a Democratic Party. First and foremost, the Solid South’s grip over congressional policymaking made the defense of Southern apartheid a national prerogative for the New Deal and the war effort. Race riots and rampant “mistreatment of Negro soldiers” dovetailed with the specific features of northern segregation such as job discrimination, restrictive covenants, and police brutality.

Moreover, the political language of the New Deal itself provided few institutional inroads for African American workers to make claims for the full rights of citizenship. Whereas millions of laboring Poles and Italians had been mobilized under the New Deal to do just that, African American workers, Brooks argued, would never be moved to try to blend into a homogenized working class defined foremost by its claim to whiteness. The European immigrant machine-tenders at the core of the New Deal coalition, Brooks noted, were not burdened by the “domestic problem” of Jim Crow with which African Americans were forced to cope. This additional burden, Brooks averred, served to separate African Americans from “the class group to which they belong.”[5]

But interracial unionism—especially in the big industrial unions of the CIO—seemed to augur a future in which an independent movement for the black proletariat might autonomously shape its own future. In the Defender’s illustrated history of black voting in Detroit, “unionism” stands out as a beacon of opportunity set against the terrorism of race riots. The deepening wartime links between the United Auto Workers and the NAACP, as August Meier and Elliot Rudwick show in their classic Black Detroit, promised to serve as the seedbed of a nascent interracial social democracy. Writing in 1943, the Trinidadian intellectual and activist C.L.R. James (then immersed in the Detroit-area anti-Stalinist Left) offered a bolder synthesis of the premises towards which Brooks and the Defender were groping:

The UAW of Detroit has repeatedly demonstrated its sympathy with the Negroes against the comparatively small section of Detroit race-baiters. Let the Negroes note this, and where, as in Detroit, they are strongly represented in the unions, let them make direct appeal to the unions for help in the organization of the defense. There are difficulties in the way. But the Negroes can overcome them if they first depend upon themselves and then call for the direct support of labor.[6]

The revolutionary James offered a concrete example to drive home the same point made by the reformist Brooks: black Detroiters needed to invent new politics and forge new coalitions to advance the struggle for equality.

***

In stark contrast, Gunnar Myrdal, saw black political integration as an almost preordained process. Myrdal the social scientist saw black migrants moving through an already established, even transhistorical, process of political development already defined by Europeans.

The Negro coming from the South to the North was as politically innocent and ignorant as the immigrant from a country like Italy where democratic politics was not well developed and was very different from politics in the Northern United States. It was quite natural, therefore, for Negro politics in the North to take forms similar to Italo-American politics.[7]

That comparison to Italian-Americans only further conveyed a stage of relative political immaturity, one dominated by the corruption and petty self-interest of machine politics.[8]

But the experience of the New Deal had clearly been transformative. Increased turnout reflected a better education in the ways of American democracy. This, in turn, meant: “On the whole, Negroes have come to be rather like whites in their political behavior in the North [italics in original].”[9]

Unlike Brooks, Myrdal envisioned a gradual and stagist process of American political integration. The comparison with Italian immigrants no doubt was meant to be encouraging: just as the Italians (or the Irish or the Jews) overcome discrimination, inequality, and powerlessness, so too would African Americans. But Myrdal’s analysis downplayed the kinds of barriers detailed by Brooks. Crucially, he also ignored the possibility that winning black political power, much less racial equality, would require militant struggle markedly different from the kind practiced by white ethnics.

Myrdal’s views reappeared in the social science literature of the postwar years. For example, Blue-Collar World, a 1964 sociological volume on the contemporary American working class, similarly predicted that the “imminent large-scale politicization” of workers of color would create the conditions for a new racially egalitarian reform movement to follow the same institutional pathway as the New Deal.[10]

Myrdal’s conclusions also reinforced the anger of nascent neoconservatives as deeply frustrated by the institutions and discourses of New Deal liberalism as they were by black protest. This frustration comes across clearly in the telling 1964 roundtable discussion hosted by Commentary featuring Myrdal, Nathan Glazer, Sidney Hook, and Nathan Glazer that Stephen Steinberg so vividly recounts in his new piece on the Moynihan Report. It also appears in Robin Marie’s recent analysis of Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Glazer’s 1970 preface to Beyond the Melting Pot.

That frustration in turn found its roots in the Detroit of 1944 where the Crisis found the “friction between the two old American traditions” of reaction and egalitarianism sharpening. The tension between the writings of Deton Brooks and Gunnar Myrdal exposes a much larger, and much longer history of conflict over who will control the tempo and tenor of the fight for equality.

Notes

[1] Louis E. Martin, “Detroit—Still Dynamite,” The Crisis (January 1944), 8.

[2] Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2008), 34. See also Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001).

[3] Lawrence D. Reddick, “What the Northern Negro Thinks About Democracy,” Journal of Educational Sociology, 17 (January 1944), 297.

[4] Edward H. Litchfield, “A Case Study of Negro Political Behavior in Detroit,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 5 (June 1941), 271.

[5] Deton J. Brooks, Jr., “Negro Vote May Swing Election to Right President,” Chicago Defender, May 20, 1944, p.1.

[6] C.L.R James, “The Race Pogroms and the Negro: The Beginnings of an Analysis,” in C.L.R. James on the ‘Negro Question,‘ ed. Scott McLemee (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1996), 45.

[7] Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy, Vol. 1 (New York: Harper and Row, 1962 [1944]), 491.

[8] See ibid., 498.

[9] Ibid., 495.

[10] Arthur B. Shostak and William Gomberg, “Introduction,” in Blue-Collar World: Studies of the American Worker, ed. Shostak and Gomberg (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1964), 6.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Kit, I’m biased, but I really love this piece. It not only fills in an important gap in the literature, but also serves as a model of how to share original research-in-progress in a forum such as this.

My question is about the CIO itself–how did the CIO leadership envision the African American vote in Northern cities? Have you seen any changes over time (within the crucial time period of 1940-1950) on the part of the CIO? Are there connections to be drawn between the history you present above and the formulation of the Operation Dixie strategy?

Thanks so much, Kurt, and again bringing me into the USIH community. The CIO into the conversation is a very crucial given the larger political project of interracial social democracy that ultimately united Brooks and Myrdal (as well as Henry Lee Moon, AP Randolph, and later Bayard Rustin). The fight for a fourth term for FDR in 1944 becomes a watershed moment in the thinking of both civil rights intellectuals and the largely white CIO leadership. The voting power of not simply black voters, but proletarian black voters, becomes a central theme of the campaign. Joseph Gaer’s almost real-time history of the CIO-PAC, The First Round (published in 1944), devotes considerable attention to civil rights and black workers. In Dayton, Ohio, for example, the CIO and the NAACP join forces to register thousands of black war workers to vote in November. That’s a scene that emerges in cities across the country, prompting DNC chair Robert Hannegan to exclaim (in the New York office of the CIO-PAC no less) that working-class black voters in eight cities could decide the election. And they did.

You raise an excellent point with Operation Dixie. I would see it as much as an effort to organize southern industry as to overthrow the segregationist Democrats (which is certainly how they saw it, as Sean Farhang and Ira Katznelson show). But moreover, Op Dixie underscored the deepening the deepening links between the labor and civil rights movements, links premised on a vision of black workers as agents of political transformation. The extent to which a Philip Murray, Sidney Hillman, or Walter Reuther ascribed to a Myrdal or Deton Brooks line would definitely be worth investigating.

My points here very much stress the anti-communist, proto-ADA civil rights-labor alliance. The role of the Communists remains another area for discussion.

Thanks for this piece, Kit and Kurt–awesome stuff.