I do not think there is much more I can say to add to the cacophony of voices that have spoken out since the horrific terror attack in Charleston, South Carolina on Wednesday night. A massacre that harkened back as much to the racial strife of Reconstruction-era violence as it did to anything in recent memory, the attack on Mother Emanuel AME Church has reminded Americans of the continued presence of anti-black, right-wing extremism that exists on our shores. Historians have performed a great public service in recent days in contextualizing the attack within the history of Charleston, of South Carolina, and of Confederate imagery. But I want to remind readers that we also need to contextualize this attack within the history of recent, extreme right-wing terrorism within the United States.

Talk about the Confederate flag flying on the statehouse grounds of South Carolina is important. As a young man who grew up in Georgia while that state still had the Confederate battle flag as part of its state flag, and growing up next to South Carolina when the debate about “the flag” last flared up, I know all too well the emotions and arguments behind this debate. Taking down the flag from in front of the statehouse in Columbia, South Carolina, would be nice. But a focus on the flag alone is a mistake. Remember, after all, that 2015 represents several milestones: one hundred fifty years since the end of the Civil War; fifty years since the passage of the Voting Rights Act; and, also, twenty years since the Oklahoma City bombing.

I bring up the Oklahoma City bombing because, in reading the manifesto written by Dylann Roof, one cannot help but think back to the rhetoric spewed forth by so-called “militia” groups in the mid-1990s. Inspired by books such as The Turner Diaries and the extremism of white supremacy organizations, Timothy McVeigh destroyed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Roof’s manifesto is the synthesis of that fear of the modern tinged with a great deal of older white supremacist ideology—much of it a throwback to Reconstruction and the later rise of Jim Crow segregation.

Roof’s example is also a reminder of the international dimensions of virulently anti-black extremism. Recall that the early image of the attacker featured Roof wearing a jacket festooned with the flags of Rhodesia and the Apartheid-era South Africa—regimes both built on white supremacy and often held up, both in the past and today, by white supremacists as oases of “civilization” in Southern Africa. Also remember that, even  today, concerns about racism cannot, and should not, be relegated to South Carolina or the Southern United States. As I write this, thousands of Haitians face the real prospect of deportation from the Dominican Republic due to anti-black racism in that nation.

today, concerns about racism cannot, and should not, be relegated to South Carolina or the Southern United States. As I write this, thousands of Haitians face the real prospect of deportation from the Dominican Republic due to anti-black racism in that nation.

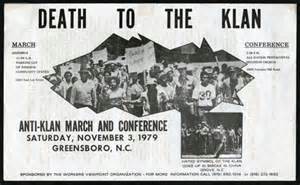

I cannot give a brief history of anti-black extremism in one blog post. But I do want us to remember the other incidents in recent memory—such as the 1979 Greensboro Massacre, or the 1981 lynching of Michael Donald, or the 1998 murder of James Byrd, Jr.—that illustrate the continued brutal force of white supremacy in modern America. Further, as intellectual historians, we cannot shy away from examining the ugly force of extremism that festers even in an increasingly tolerant, multi-cultural, cosmopolitan United States.

0