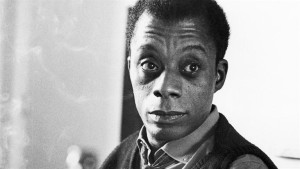

Last week, I spent a few days reading James Baldwin’s No Name in the Street. I knew immediately that I was going to have to write a post about this, but I was at a loss, initially, as to what to say.

That’s because No Name in the Street

is so good that I was afraid any attempt to explain why would devolve into block quote after block quote, followed up by commentary that basically amounted to “and isn’t that amazing?!?”

Fortunately, I found a focus to rope together my unwieldy enthusiasm, for I am planning on using No Name in the Street

for teaching, and I think there are several things about it that highly recommend its use for any course that explores in part or in whole either the history of American racism or the post-war period more generally.

First, No Name in the Street brings the best of both biography and social critique without the disadvantages of either. Baldwin effortlessly weaves in a roughly linear narrative of his life with commentary so sharp and honest that it penetrates past whatever initial resistance it might encounter, forcing the reader to reckon with it. Moreover, in addition to encouraging the empathy central to historical thinking, Baldwin’s narrative provides an on-the-ground review of many of the major moments of the civil rights movement, from the inspirational actions in the South to the devastating loss of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. By illustrating how social critique relates to lived experience, No Name in the Street invites students to connect the usual recounting of the black freedom struggle to the inescapable anguish of living under white supremacy that black Americans endured and continue to endure.

Which is not to say, however, that No Name in the Street makes for easy reading. While his style is incredibly clear, Baldwin does not mince words, making his book simultaneously accessible and acutely challenging. On page after page, he brings the full power of his rhetorical brilliance to the table, condemning the history of racial injustice in America without hesitation or apology. For example, after recounting the tragic fate of an intelligent, young black man who had lost his brilliance to insanity, Baldwin elaborates on his inability, despite his desire, to love his country; for “everything that might have charmed me merely reminded me of how many were excluded, how many were suffering and groaning and dying, not far from a paradise which was itself but another circle of hell.”[1] A little bit later in the text, he returns to this theme – one of the main messages, it seems, Baldwin is attempting to communicate in the book – when discussing the rapacious exploitation of ghetto residents by life insurance companies. “And let me state candidly, and I know, in this instance, that I do not speak only for myself, that every time I hear the black people of this country referred to as ‘shiftless’ and ‘lazy,’ every time it is implied that the blacks deserve their condition here (look at the Irish! look at the Poles! Yes. Look at them.) I think of all the pain and sweat with which these greasy dimes were earned, with what trust they were given, in order to make the difficult passage somewhat easier for the living, in order to show honor to the dead, and I then have no compassion whatever for this country, or my countrymen.”[2] Considering my research on the rhetoric of the culture of poverty, I found this passage particularly devastating in its cutting, relentless honesty.

Students, however, are likely to be unfamiliar with such open critiques of patriotism – even the multicultural education they might have received in primary school and high school probably still adhered to the narrative of redemption for America, built upon the belief that the nation is defined by its better self. Baldwin, however, refuses to accept any depiction of America that doesn’t place the suffering of the black and the poor at the center of the picture – for the country itself, he earlier argued

with William F. Buckley, was literately built by the hands of exploited. As a consequence, he flatly rejects any notion of a core of redeeming values at the heart of the American project; rather, Baldwin sees America as a cruel, psychologically twisted land, filled with the “human wreckage” of both the oppressed and the oppressor.[3]

Such an uncompromisingly critical stance is likely to be challenging for some students, but I think this provides an excellent opportunity for teaching the art of historical thinking. By encouraging students to both react to and reckon with Baldwin’s claims, we can use his harsh assessments of America as a starting point for learning to not merely reject or accept a certain viewpoint, but to first, and fundamentally, understand it and the historical context in which it developed.

Finally, it is perhaps easier to do this with No Name in the Street than other texts, for unfortunately, so much of what Baldwin writes is not merely relevant to the present, but is almost indistinguishable from current commentary on the Black Lives Matter movement. For example, consider the following passage, where Baldwin is elaborating on the thick gel of ideology which makes communicating to white Americans almost impossible: “It means nothing, therefore, to say to so thoroughly insulated a people that the forces of crime and the forces of law and order work hand in hand in the ghetto, bleeding it day and night. It means nothing to say that, in the eyes of the black and the poor certainly, the principle distinction between a policeman and a criminal is to be found in their attire.”[4] Upon reading this, I couldn’t help but think of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay about the hypocrisy of the representatives of the state calling for nonviolence during the Baltimore riots. “When nonviolence begins halfway through the war with the aggressor calling time out,” Coates writes, “it exposes itself as a ruse.” Similarly, what else could be brought to mind, after reading this passage from Baldwin, but the recent spate of videos showing a complete unwillingness on the part of the police to simply listen to the complaints, concerns, and explanations of citizens who quickly discovered they are not regarded as possessing rights? “The white cop in the ghetto is as ignorant as he is frightened, and his entire concept of police work is to cow the natives. He is not compelled to answer to these natives for anything he does; whatever he does, he knows that he will be protected by his brothers, who will allow nothing to stain the honor of the force.”[5]

My point here is not to say that Coates is the new Baldwin, or that there are no important differences in white supremacy to take note of since 1970. Rather, I think Baldwin’s bold passages – and the striking similarity many of them have to key arguments of contemporary black commentators – is a great starting point for conversations about both what is usually regarded as the key object of historical study, change, and its necessary counterpart, continuity. In what ways has racism changed since Baldwin wrote No Name in the Street, and in what other ways has it remained the same? For that which has changed, where does this change principally lie – in content or in form? The fact that Baldwin talks about issues remaining so relevant to contemporary Americans should assist students in thinking critically about these questions and taking them seriously. At least, I ever so much hope so; for, as Baldwin also writes, even in the midst of a book brimming with pessimism, “yet hope – the hope that we, human beings, can be better than we are – dies hard; perhaps one can no longer live if one allows that hope to die.”[6] And such a hope, I think, rests at the heart of the art of teaching.

[1] James Baldwin, No Name in the Street (New York: Vintage International, 1972), 126.

James Baldwin, No Name in the Street, 162-163.

[3] James Baldwin, No Name in the Street, 162.

[4] James Baldwin, No Name in the Street, 161.

[5] James Baldwin, No Name in the Street, 163.

[6] James Baldwin, No Name in the Street, 36.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this, Robin. I confess my prior ignorance of Baldwin’s *No Name in the Street*. I think students will respond positively if put in the larger context of historical thinking, particularly the terms you identify (change, continuity). – TL