————————————————

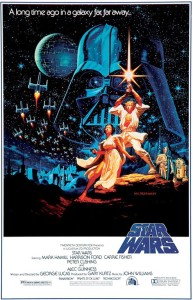

Where does one begin to discuss a phenomenon like Star Wars

? What can be said that hasn’t already been said about a blockbuster franchise of that magnitude? And what is it to think about Star Wars as an object of intellectual history?

That kind of history would, of course, bear the marks of cultural analysis as well as the identification of ideology and prior existing, or new, structures of thought. On the production side, the film creator’s inspirations and intention would receive attention. In this case the basic story and script would be analyzed. The biographies of the producer and director matter in relation to the animation of the story’s main characters, events, sets. Actors’ contributions would be assessed in relation to the intentions of producer and director. On the consumption side, reception must be analyzed. What did the critics have to say? How did audiences react? What of the number of viewings and the economics of consumption? Finally, how did the film influence subsequent films (i.e. a franchise)? What is a single film’s place in the long history of film?

As is clear from the above points and questions, writing an intellectual history of any one film, from the Star Wars franchise or otherwise, could involve numerous intellectual history components. Given the detail involved in intellectual histories, the narrative would likely be overly long, otherwise any one analysis would have to focus on a particular aspect of a film’s life.

In my own professional life, I have a penchant for analyzing reception. I am perpetually intrigued to see examples of how thoughtful people react to, and engage, the artistic and literary creations of others. I love exploring how the minds of creators connect, or not, with their audiences. In the case of the original Star Wars (now Episode IV), because I was so young when the film came out (saw it late in 1977 or in 1978, at what was then the Crest Drive-In Theater in Kansas City, Missouri), my reaction was pure awe. I was dazzled and intrigued by the world I had just seen. No articulate intellectual response was possible, for me at least. That part of my life is such “a long time ago” and so “far, far away,” that I’m now intrigued to explore the artistry of responses to the film.

To be clear, what follows is only a look at thoughtful responses to the first movie in the franchise, Star Wars. That installment first appeared in May 1977.

What of the basics? I won’t rehash the story line here. I feel pretty safe in assuming that most readers know the plot and main characters, as well as many spoilers revealed in later installments. What of the first material response, at the box office? According to AMC’s Filmsite.org, the film cost $11 million to produce, but grossed $307 million domestic and $775 million worldwide. It won six Academy Awards for Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design, Best Film Editing, Best Score, Best Sound, and Best Visual Effects. Later it would win a Special Achievement award for Sound Effects. Needles to say, the film had the attention of the film industry.

Comic Relief That’s Not Tacky: Canby’s New York Times Review

The New York Times reviewed the film on May 26, 1997. The reviewer was Vincent Canby. Canby called it “the most elaborate, most expensive, most beautiful serial movie ever made.” Canby, however, emphasized the film’s links to comic strips and books which, as of the late 1970s, were associated with less-than-serious “literary” endeavors. With that in mind, Canby noted that Star Wars was “fun and funny.” Indeed, the title of the review was “A Trip to a Far Galaxy That’s Fun and Funny…” R2-D2 and C-3PO are called “Laurel-and-Hardyish robots” who might be “the year’s best new comedy team.”[1]

That final ellipses in the title is interesting. Canby implores the reader and potential film viewer to “definitely not…approach ‘Star Wars’…[as] a film of cosmic implications.”[2] But the ellipses invite doubt, at least, or something more. It’s almost as if Canby knew that many would find larger meanings in the story arc of Luke Skywalker as a Campbellian hero on a mission to find himself, or in the truly cosmic battle between good and evil that permeates the film. Or in the way that Star Wars melds science fiction with history and religion. How could a film tapping those deep currents in humanity not invite cosmic questions of the audience?

Canby, however, in the review returns to film’s comic roots. He prompts the reader about the film’s “breathless succession of escapes, pursuits, dangerous missions, [and] unexpected encounters.” Continuing with his farcical take on the contents, he notes “an old mystic named Ben Kenobi…one of the last of the Old Guard, a fellow in possession of what’s called ‘the force’, a mixture of what appears to be ESP and early Christian faith.” Of course Canby comments on the Cantina scene, with its “very funny sequence” involving “a low-life bar…a frontierlike establishment where they serve customers who look like turtles, apes, pythons and various amalgams of the same.” [3]

Much as one would compliment the superb artistry of certain comic books, Canby argues that “the true stars” of the film are “John Barry, who was responsible for the production design, and the people who were responsible for the incredible special effects.” The best credit he could give George Lucas was that he could “recall the tackiness of the old comic strips and serials he loves without making a movie that is, itself, tacky.” [4]

Any success in the fantasy and/or science fiction genre couldn’t possibly siphon from deeper currents in human storytelling, or longing, or the larger desire for transcendence. Humor and special effects couldn’t also coexist with a seriousness about the human search for meaning. No, any success the film might obtain would purchase from trickery and humor alone. Entertainment and meaning had to come from different wellsprings.

Big and Relevant Ideas: The Daily Telegraph (UK)

On December 16, 1977, The Daily Telegraph published a review from its science correspondent, Adrian Berry (“4th Viscount Camrose and a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society”).[5] To say that Berry took a different tack is an understatement. Here are the opening paragraphs of his piece (bolds mine):

Until recently, space melodrama films have tended to be made with neither imagination nor money. With the brilliant exception of the Clarke-Kubrick “2001: A Space Odyssey,” they have been badly-written B-feature affairs from producers with little knowledge of astronomy or technology.

Star Wars (Leicester Square and Dominion, Tottenham Court Road, “U” from Dec. 27) is far removed from these shoddy productions. It is the best such film since “2001,” and in certain respects it is one of the most exciting ever made.[6]

Berry notes the films politics early on:

A group of unscrupulous interstellar politicians have overthrown the legitimate authority and created an evil galactic empire. But the beautiful Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) a leader of the defeated party, starts a rebellion to restore democracy. She learns of the usurpers’ frightful new weapon, the “Death-Star,” a travelling artificial moon with sufficient fire-power to disintegrate a planet.

With the help of a handsome young farmer (Mark Hamill) and an ageing warrior with awesome telepathic powers (Sir Alec Guinness), she starts a resistance against the evil junta which leads to explosions, murders, ferocious space battles and her own imprisonment in durance vile.[7]

It isn’t humor that attracted Berry, but empire, evil juntas, revolutionary resistance, gender, democracy, and technology gone wrong. All of these themes and topics would be relevant to 1970s viewers who had undergone the traumas of the 1960s. Vietnam was not far from Western readers’ minds.

Berry seems convinced that Lucas has produced not only a relevant film, but one that might be predictive of the future. He adds: “The scriptwriter (George Lucas) wrote five separate drafts before he was satisfied (imagine one of those B-feature fellows doing that!), and the effect is to persuade us that there is little in this film which may not one day happen in real life.”[8]

Conclusion

What an amazing difference seven months made in the tone of this admittedly super small, blog-sized sampling of reviews. What is most striking is the change from viewing the film as a comedy to something more like a science-fiction drama. One review reveals a film built for eight-year-olds primarily. The other indicates, and I quote, that “people aged between 7 and 70 will be jamming the box office” to see Star Wars.

I was either 7 or 8 years old when I was taken to the film. I’m pretty sure I didn’t see it until I was at least 7 (that birthday came in August 1978). My mother probably took me to an inexpensive second running at the drive-in. Age aside, I remember being intrigued the most by the cosmic battle between good and evil.

It was a science-fiction historical romance to me. The light sabers were awesome, but so were the evil pursed lips of Peter Cushing—aka the Grand Moff Tarkin—and the high character of Ben Kenobi. I remember being confused by Han Solo’s moral ambiguity (how could he not help destroy the Death Star?!).Star Wars functioned more as a moral adventure for this little boy than any kind of comic book-style frittering away of time and meaning (at least in terms of Canby’s sense of 1970s comic books). Although I couldn’t articulate this at the time, George Lucas introduced me to a cosmic tension that I’m still working out in my life. I suspect that kind of meaning drew, and still draws, more people to the franchise than its glitzy special effects. It’s a lesson I’m not sure Lucas remembered fully when he made the prequels. I hope that the new episodes, which begin this next winter, renew engagement with that long battle of good versus evil.

————————————————

Notes

[1] Vincent Canby, “‘Star Wars’: A Trip to a Far Galaxy That’s Fun and Funny. . .,” The New York Times, May 26, 1977. http://www.nytimes.com/1977/05/26/movies/moviesspecial/26STAR.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Adrian Berry, “Star Wars: Episode IV: A New Hope Review,” The Daily Telegraph (UK), December 16, 1977, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/film/star-wars–a-new-hope/review/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is a really, really fascinating take on “A New Hope.” How much do you think the national backgrounds of the two reviewers had anything to do with the reviews, if anything at all? Certainly, with Berry being a member of the Royal Astronomical Society I can see him being a bit more open to thinking big–but his review, as you state, is much more about the ideas behind the Rebellion and the Empire. Is there something in the British entertainment tradition that might have also led Berry to take the ideas of the movie more seriously than Canby?

Also, one more thing about the British POV–“Star Wars” came out in the UK a few months before a landmark science fiction series, “Blake’s 7,” premiered on BBC1. That series went even a step further than “A New Hope” in telling a story about rebellion against a cruel empire, except in this case the fight seemed less optimistic and more morally ambiguous. And then there’s “Judge Dredd” in the UK’s “2000 A.D.” comic anthology series, which came out in 1977; and “Doctor Who” was in its Tom Baker era, when the Doctor was played a bit more alien and aloof.

Sorry for that long detour, but British science fiction was in an interesting place in the late 1970s, and “Star Wars” entering the fray just as British science fiction was taking on “grittier” themes and the nation as a whole was on the eve of embracing Thatcherism is an interesting topic.

Robert: Thanks for the comment. I confess my ignorance of British sci-fi, inclusive of all the programs you mention. I’m not a Doctor Who fan, so I was unaware of its beginnings and iterations. Otherwise, I’m not sure of the long history of British film and television entertainment, so I can’t speak to why Berry was more open to Saganesque thinking about the film’s “cosmic implications.” I was just shocked that Canby could NOT see a larger framework for reception. – TL

If you consider what movie sci-fi was like from the late ’60s up to Star Wars, you can understand why folks found it so extraordinary. It was all Charlton Heston and dystopian fantasies: Planet of the Apes, The Omega Man, Silent Running, Soylent Green, Westworld, Logan’s Run, etc. Don’t forget George Lucas made his own contribution with THX-1138. 2001 doesn’t quite fall into that camp, but it’s an austere, distant, forbidding movie. If you’d been seeing this sort of thing for the last decade, you’d have walked out of the theater in 1977 thinking, “What the hell did I just see?! Now let me see it again!!!” And those movies I mentioned do look kind of “shoddy,” as the British reviewer notes. Star Wars really was like nothing anyone had seen when it came out.

Robert, have you watched Blake’s 7? If so, you should do a Star Trek vs. Blake’s 7 post sometime. It’s rep has always been that it’s the anti-Star Trek.

One interesting note: academics have been interested in Star Wars since the moment it came out. As far as I can tell, this is the first scholarly article ever published about it: Robert G. Collins, “Star Wars: The Pastiche of Myth and the Yearning for a Past Future,” Journal of Popular Culture 11 (1977): 1-10. This was the summer 1977 issue. I’m not sure when exactly it would have been published, but I’d somewhere between July and September. In other words, only a handful of months after its release.

Varad: Thanks for the comment.

I’m totally with you on the context. The “special effects” in those older Buck Rogers’ films were extraordinarily basic. And I’m with Canby on noting the contrast and praising what he saw in Star Wars. I was surprised, however, that he couldn’t see the larger ideas and potential implications that Berry plainly saw. There’s so much more going on in the film.

What a great citation find with regard to Collins. He must have seen it, worked up his piece, and received an early nod form the JPC editor. Amazing. In today’s environment it would take a year to get that piece published. …Now I want to know what the article says. Have you read it? – TL

Tim – I wonder if it made a difference that Berry was writing six months after Canby. Perhaps that was enough time for some of the themes in the movie to have become apparent, or at least discussed more, which then migrated across the Atlantic. Who knows? There’s probably a lot of interesting stuff lurking in the first year of reaction to Star Wars.

Speaking of, as far as I can gather I have not read the Collins article. I have the PDF, but I don’t cite him in my paper, and I don’t have a copy of it in my folder of Star Wars articles. I’ll have to take a look at it to see what the gist is. FYI, Collins was an English prof who wrote about Woolf, Faulkner, and Joyce, among others. So why not George Lucas?! As for the quick turnaround, I imagine everyone recognized what a phenomenon it was. And as you suggest, it was probably easier back then to move quickly. The next year saw several more such articles.

One of my favorites from recent years is one which reads Lucas’ movies (including Star Wars) as riffs on Herbert Marcuse. That one has to be read to be believed, and even then I’m not sure you will. Here’s the link to it:

http://online.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/abs/10.3828/extr.2009.50.3.4?journalCode=extr

Growing up outside of Peoria, Illinois, I cut my teeth on the original Star Trek. After its cancellation, I would race home from school to catch it on television. I was a teenager when I saw Star Wars in the theater. Even then I was struck by Star Wars anti-intellectualism and anti-rationalism. In the typical Star Trek episode, our heroes would at least make an effort to think their way our of the particular jam of the week.

But Star Wars was different instead of having our heroes being dedicated to logical scientific thought and being the best and the brightest of an intergalactic democracy, the heroes of Star Wars are literally a princess, a hereditary line of knights, (I confess stretching the analogy, but the Force runs strong through families,) and a magic wielding Gandalf. I mean Obi-Wan.

For a discussion of Death Star politics, I present the following clip. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGOVbXF7Iog