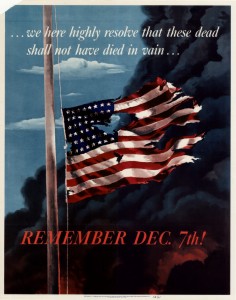

I don’t study urban politics or the history of civil unrest, but I do study the relationship between violence, death, and meaning in America. The death of black men in America recently and historically don’t often figure into the myths I come across. And yet, as the photo that introduces this post declares, they should, for surely these men didn’t (and shouldn’t have) died in vain.

I don’t study urban politics or the history of civil unrest, but I do study the relationship between violence, death, and meaning in America. The death of black men in America recently and historically don’t often figure into the myths I come across. And yet, as the photo that introduces this post declares, they should, for surely these men didn’t (and shouldn’t have) died in vain.

That phrasing echoes, of course, the most famous statement made about death in America–Lincoln’s exhortation to those gathered in November 1863 at the dedication of the Gettysburg Cemetery: “that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom…” We commemorate the dead in wars in a remarkable ways. We celebrate their sacrifices. We build monuments to their legacies. We honor the wars they fought in–this year alone there are commemorations of the end of the American Civil War 150 years ago, the 100th anniversary of the First World War, the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, and a debate about the inglorious exit of the United States from the Vietnam War.

That phrasing echoes, of course, the most famous statement made about death in America–Lincoln’s exhortation to those gathered in November 1863 at the dedication of the Gettysburg Cemetery: “that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom…” We commemorate the dead in wars in a remarkable ways. We celebrate their sacrifices. We build monuments to their legacies. We honor the wars they fought in–this year alone there are commemorations of the end of the American Civil War 150 years ago, the 100th anniversary of the First World War, the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, and a debate about the inglorious exit of the United States from the Vietnam War.

When we consider the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore and other black men in America at the hands of police or their surrogates through “extra-legal justice,” are we not talking about war or, at least, violence operating under the guise of the state?

Stanley Hauerwas, the Duke theologian and pacifist, writes that “War names the time we send the youth to kill and die in an effort to assure ourselves the lives we lead are worthy of such sacrifices…War makes clear we must believe in something even if we are not sure what that something is, except that it has something to do with the ‘American Way of Life.’” What happens when death in war makes clear that “that something” is (or should be) antithetical to the American Way of Life? In regard to wars of imperialism, I think of Mark Twain’s “The War Prayer” or the family of Pat Tillman refusing to allow the Bush administration to use his death to find meaning in the War on Terror. In regard to the wars raged in our cities, what do we ascribe to the photos of Eric Garner lying dead in Staten Island or the broken buildings of Baltimore? We seem to have little problem assigning meaning to the dead at Gettysburg or the burned out structures of Charleston, South Carolina.

Stanley Hauerwas, the Duke theologian and pacifist, writes that “War names the time we send the youth to kill and die in an effort to assure ourselves the lives we lead are worthy of such sacrifices…War makes clear we must believe in something even if we are not sure what that something is, except that it has something to do with the ‘American Way of Life.’” What happens when death in war makes clear that “that something” is (or should be) antithetical to the American Way of Life? In regard to wars of imperialism, I think of Mark Twain’s “The War Prayer” or the family of Pat Tillman refusing to allow the Bush administration to use his death to find meaning in the War on Terror. In regard to the wars raged in our cities, what do we ascribe to the photos of Eric Garner lying dead in Staten Island or the broken buildings of Baltimore? We seem to have little problem assigning meaning to the dead at Gettysburg or the burned out structures of Charleston, South Carolina.

I know that ultimately what I study is a ruse–the illusion that meaning unlocked from those iconic photographs has moral clarity. But I also know that the deaths they represent are no illusion, even if the myths we generate about them are.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Professor Haberski,

Your piece is interesting, thought provoking, and for some readers, it might be disturbing.

I find it interesting to examine the choices we make when constructing narratives. In our personal lives, we tend to present the best possible version of ourselves most of the time. But what do we do when “reality” doesn’t neatly fit with our constructed identity? How do citizens deal with narratives that don’t fit with their preconceived notions of American exceptionalism? How do Americans deal with their own shortcomings in following our civil religion? Is it really that much of a shock that some might cope by dissociative amnesia?

Unless one is a historian of indigenous peoples, slavery, abolitionism, or race relations, one tends to accept a triumphant, progressive narrative of U.S. history.

Who died at the Boston Massacre? I bet a roomful of non revolutionary era historians could answer “Crispus Attucks,” but how many could name even one other victim? Why do we privilege Crispus Attucks life? Is it because his story provides comfort in multicultural America?

Thanks Brian, for both your comments and for simply responding to this difficult post. The idea for it came out of the disjunction or collision of having spent a morning with a few of my students walking around one of Indy’s many war memorials, this one is the massive gray temple built in the 1920s with an interior room that is spectacular because it is so ornate. You can see it here: http://www.where-we-live.org/2012/07/indiana-war-memorial-shrine-room-an-architectural-head-rush.html.

Anyway, I was stuck by the way photographs and monuments to violence and death grow into one type of icon while photographs of dead or dying black men and burned out structures in Baltimore or Ferguson get translated into the antithesis of the images of the wars America has waged. Frankly, I am very ambivalent about finding meaning in any of it but it is difficult not find that contrast demoralizing in a constructive way.

As you suggest, no one should be surprised by when collective amnesia makes interpretative symmetry unlikely. And I don’t expect us to have a national conversation that will address the role killing plays in creating an American narrative. Sometimes, though, I wonder if we don’t do enough on subject of death and killing, at least I don’t know how we might do this better.