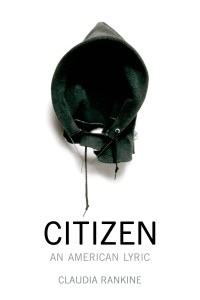

On one of the pages of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, we encounter an anecdote about author headshots. Rankine tells us that “a friend” approached her to ask why a photo he ran across on the Internet “look[ed] so angry.” Rankine finds this question strange, as she had worked with the photographer to choose the one in which she looked “the most relaxed.” “Obviously this unsmiling image of you [i.e., of Rankine] makes him uncomfortable, and he needs you to account for that.”

On one of the pages of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, we encounter an anecdote about author headshots. Rankine tells us that “a friend” approached her to ask why a photo he ran across on the Internet “look[ed] so angry.” Rankine finds this question strange, as she had worked with the photographer to choose the one in which she looked “the most relaxed.” “Obviously this unsmiling image of you [i.e., of Rankine] makes him uncomfortable, and he needs you to account for that.”

Citizen is filled with moments like these, moments in which Rankine encounters a speaker who asks her to justify herself in a sort of Jeopardy style: state your demand in the form of a question. “Why do you look so angry?” or “Wasn’t there a picture of you smiling?” Rankine’s friend might be asking. The friend needs Rankine “to account for that,” with “that” standing in for, oh, just about everything.

But it is not just the unanswerability of these questions that Rankine describes so pointedly; it is the vividness of the affects which accompany being forced to listen to them and to try to answer them that is the real gut-punch of the book. “Certain moments send adrenaline to the heart, dry out the tongue, and clog the lungs. Like thunder they drown you in sound, no, like lighting they strike you across the larynx,” she writes about the aftermath of having a close white friend call her by the name of that friend’s black housekeeper. “Dysphoria” is almost the only word I can think of for this kind of all-encompassing discordance, this silencing, imprisoning sensation which Rankine describes.

But what is dysphoria? Last week

I tried to think through the term euphoria a bit, basing my thoughts on the novel by that name by Lily King, an extraordinary novel loosely generated from the lives of Margaret Mead and two of her husbands. Today I want to think about dysphoria—not a pleasant undertaking—both in terms of what it seems to be trying to do and what it cannot do. Dysphoria, I think, is the name of an affect experienced during moments when one tries to, but cannot, bridge the individual and the structural, when one is addressed not as a person but as a member of a group, but nonetheless is allowed to answer back—if at all—only as an individual, without recourse to arguments about society or about culture or about power. “Why do you look so angry?” is constructed as a question that you can answer only as the singular you even when it means you-plural.

Consider the term “gender dysphoria.” I am looking at the APA report dealing with a terminological change in the new DSM-5: the diagnosis for “people whose gender at birth is contrary to the one they identify with,” which was called “gender identity disorder” in the DSM-IV, is now to be called “gender dysphoria.” The APA notes that this change is necessary because the implication that a person with this condition is “disordered” is undesirable. “It is important to note,” the report says, “that gender nonconformity is not in itself a mental disorder.”

The report goes on, however, to mystify the nature of gender dysphoria: no longer eager to insist that the problem is located internally—there’s something wrong with you if you feel you were “born the wrong gender”—it bends over backwards to avoid drawing the opposite conclusion, that the “problem” is obviously social, the problem is with the way our society assigns gender in a binary and immutable fashion. Observe how ostentatiously neutral this language is: “The critical element of gender dysphoria is the presence of clinically significant distress associated with the condition… This condition causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.”

Yet there is just a slight sense in this report that the condition still emanates from within: “In children, the desire to be of the other gender must be present and verbalized… Gender dysphoria is manifested in a variety of ways, including strong desires to be treated as the other gender or to be rid of one’s sex characteristics, or a strong conviction that one has feelings and reactions typical of the other gender.” Desire, desire, conviction—why must you have these desires? Even as the APA moves away from an overtly stigmatizing language of disorder, the onus is still on the individual to account for why they have these “convictions.” It is only a small step to the kind of conversations–what this article calls “inquisition mode“–that calls trans* people to account for why anyone has these convictions at all.

Another way of addressing the impossible situation that the term “gender dysphoria” both names and thus in a strong sense also repeats is asking if such a thing as “gender euphoria” could exist. Would it be the utter conviction that one was born the “right” gender? What would that mean? To me, that is nonsensical, although I suppose gender essentialists could find easy sense in it. But would it be any different from believing that one was born into the “right” race?

Some of these thoughts flickered through my head as I watched Bruce Jenner’s interview with Diane Sawyer. Jenner’s effervescence during many of the exchanges seemed to express something more than relief at being finally able to acknowledge something publicly that had been a private torment, something more than the catharsis of being able to tell his life’s story as it really was. There was also a keen sense of expectation, both in regards to his transition and to the social impact that his story could have, to, as he said, the “real good in the world” that he hoped the publicity surrounding his story would create.[1]

I don’t know that this effervescence could be called euphoria, but I know that Jenner’s casual but earnest conjoining of his story with the hope for an imminent social transformation in the status of trans* people in the U.S. could only be uttered seriously by someone bearing the kinds of privilege that Jenner bears. “Euphoria” in this context is precisely that casualness that white men[2] especially have such easy terms in accessing (and here I acknowledge the reflexivity entailed in writing this): the ability to bridge the individual and the social (or the specific and the universal) without a thought and to take for granted that others will not find that bridging confusing.

More simply, euphoria means never having to answer, Wasn’t there a picture of you smiling?

[1] As has been widely noted, Jenner has indicated that he will continue to use male pronouns and the given name Bruce for the time being.

[2] edit 5:40MST I realized belatedly that this sentence could be construed as a misgendering of Jenner. The argument here is that Jenner at the time of the interview could largely share the kind of privilege that white men take for granted.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

How does the DSM define gender? (Does it?)

I found the Bruce Jenner interview deeply moving, but I wonder if it can be read in ways that make gender euphoria *more* difficult for others… by reinforcing our most traditional gender constructions. Bruce poignantly described his struggles and the relief provided by surgeries and hormone treatment. He also mentioned looking forward to wearing his hair long, painting his nails, and putting on a dress — activities he feels are central to living as a woman, whether he has additional surgeries or not. Let’s add to this the TV portrait of his enormously popular and influential female family members: the Kardashian women’s obsession with their physical appearance and their deep materialism.

Jenner & his family should be free to express their identities however they wish. But how should we determine what the baseline gender definitions are, so as to diagnose whether someone conforms or does not? Should the DSM implicitly reinforce narrow, damaging, and traditional definitions of gender? Why not simply use the term identity, rather than gender identity? Or offer another term that allows for a wider expression of self and sex?

What becomes of people who identify as women but do not have long hair, manicured nails, or an obsession with shopping? Or men with long hair who wear nail polish? Are we creating a culture in which they are less likely to experience gender euphoria?

And a related question: what to make of the Kardashians’ predilection for plastic surgeries & other cosmetic treatments to enhance breasts, butts, lips, etc.? Do they have a gender dysphoria? Or do they conform to our understanding of naturally feminine behavior?

Lovely piece, Andy. Two texts come to mind as germane: Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie (a strange book that is both great and terrible, but definitely important) and Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings (particularly Ch 4, on “irritation,” see especially discussion of Aristotle on emotions and politics of dysphoria).

SZ, you raise some really important questions. I guess I wasn’t trying to posit the idea of “gender euphoria” as some kind of higher level of happiness, more to highlight the way that the concept itself is kind of strange or at least unfamiliar. Feeling wholly comfortable in one’s gender–that seems like such an unusual or unlikely state, as even women as conventionally beautiful as the Kardashians reveal. At least, that was what I was trying to get at by musing on the idea of gender euphoria.

Kurt, thanks as always for these great recommendations. I’ve skimmed part of Ngai’s work before and find it fascinating, but really should spend the time to read it thoroughly!