[This post is part of the USIH Blog’s participation in this year’s edition of the For the Love of Film blogathon, hosted today by This Island Rod. This year’s theme is science fiction. And, as always, the purpose of the blogathon is to raise money to help the National Film Preservation Society restore a film. This year, we’re raising money to restore the 1918 Strand Comedy Cupid in Quarantine. Please consider donating to the effort here.]

Science fiction is a wonderful tool for telling stories with a larger political, social, and cultural context. As written elsewhere for this series of blog posts on science fiction, the genre offers unique ways in which to use dramatic forms of metaphor to make a point that never leaves the minds of audience members. The Brother From Another Planet, the 1984 science fiction classic directed by John Sayles, is one such example.

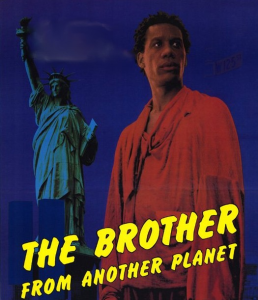

Starring versatile actor Joe Morton, The Brother From Another Planet’s plot is straightforward: an alien who happens to look like a young adult black male lands on Earth, on the run from two aliens (Sayles and David Strathairn) who happen to look like adult white males (and are a different take on the “men in black” concept). Already, the metaphor for the history of American race relations is quite apparent. The symbolism doesn’t stop there—in fact, it begins elsewhere, at Ellis Island. This is where “The Brother” (the name for Morton’s otherwise nameless character) first lands on Earth. It is also here where the film begins making sense of what America means to African Americans.

The Brother’s story on Earth starting at Ellis Island makes sense. The Brother From Another Planet is as much about New York City in the 1980s as it is about American race relations. The sense of nostalgia many Americans feel when thinking about immigration and Ellis Island comes through in this movie thanks to The Brother’s telepathic powers—while at Ellis Island, he’s able to “hear” the voices of immigrants from generations past in an otherwise empty, but once bustling, immigration center. Due to the ability of The Brother to hear voices from the past, New York City itself becomes a character in the film, reflecting both its proud past as an immigration center, and its then-present fears of urban decay and drug-fueled skyrocketing crime rates. His disheveled look in the first half of the film is a call-back to runaway slaves. The Brother’s loss of a foot while crash landing his escape pod at the start of the film, in fact, was a reminder for me of Kunta Kinte’s loss of a foot after trying to escape one too many times in Roots.

It’s also worth noting that The Brother cannot speak either. He can understand everyone around him, but he cannot talk back to them in response. This creates a movie where everyone takes turns talking to The Brother while he acts as an innocent, never judgmental yet perspective stand-in for the audience. Critics in the 1980s, most especially Roger Ebert, argued this was a trope similar to silent films of the past. Ebert wrote in 1984 that Sayles, “by using a central character who cannot talk—he is sometimes able to explore the kinds of scenes that haven’t been possible since the death of silent film.”

The verbal silence of The Brother allows viewers to see the inside of life in New York City circa 1984. A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the idea of the urban crisis in science fiction. The Brother From Another Planet is another example of that, but unlike the other films that take place in the future and speak to America’s worse fears, this movie gives a richer portrait of life in the big city. The Brother encounters all types of black people, not surprising for a new resident of Harlem: older African Americans nostalgic for an older Harlem, shrouded in history and mythology; younger black residents of the city, some working hard for a better life and others victims of the drug industry; Hispanic residents navigating cultural and language barriers in New York; and white Americans struggling to make sense of a complicated racial and ethnic melting pot.

The question of where The Brother is from becomes a pressing one for many of the characters in the movie. Some think he might be from uptown, which explains his strange aloofness. Or is he from the South, as one of the few white characters in the film (a white women married to a black man and with a biracial son and who is, herself, from the South) believes? The viewers understand why The Brother always points up to the sky to explain where he’s from, but everyone else sees it as having a different meaning.

The Brother From Another Planet is both a story of immigration and being black in American culture. As I viewed the movie again this weekend, I found myself wondering how different the film would be if it were made today. The theme of immigration might be handled a bit differently—whenever the human characters interacted with the two “men in black” chasing The Brother, they expressed hostility towards the idea of being hunted down simply for being an illegal immigrant. Between modern-day debates about immigration and the fears of terrorism in our post-9/11 world, one wonders how a strange man who can’t talk but possesses incredible powers of fixing anything—and anyone—who is broken would be treated in a fictional context.

As for how the film tackles race, the fact that The Brother immediately runs from the first police officer he sees—recognizing in the attire of the officer an authority figure—is another reminder of how old modern questions about the relationship between the police and young black youths in American cities actually are. To its credit, The Brother From Another Planet offers complicated views of many of its human characters, many of whom see The Brother as a friendly, if not talkative, figure to whom they can express their fears about New York and their own lives. The Brother From Another Planet is an example of science fiction as social commentary and social satire, a sobering reminder that many of the questions about race in American life are long lasting.

0