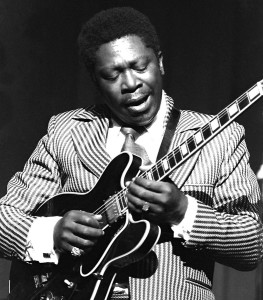

Last week people across the world mourned the passing of Blues legend B.B. King. His legacy as a musician has been secure for decades. One of the hardest working men in show business (at the least enough of a hard worker to have an excellent show with the hardest working man in show business, James Brown), King’s career is an example of the larger African American experience in music and American entertainment. In my post for today, I am going to consider another part of King’s legacy. Later in his career, B.B. King was gravely concerned about the status of the Blues among African American listeners. Was it still a musical form, by the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, being consumed by African American listeners? Or had it become a genre mainly listened to by white listeners? And, finally, why should this question matter to intellectual historians?

Questions about African American identity and American music have long been a concern for intellectuals, lay listeners of music, and musicians. From Al Jolson’s performances in blackface in the early 20th century, to concerns about the appropriation of “black” music by superstars such as Elvis Presley, to modern-day debates about the merits of white hip hop artists such as Eminem and Iggy Azalea, the interrelated questions of who can perform “black” music and, more importantly, just what constitutes “black” music, has shaped modern American understandings of popular music.[1] The blues has been no less plagued by this question.

As far back as 1979, readers in Ebony magazine were treated to this debate. The timing of this was not a coincidence. Consider the release of a recent book, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South by Charles L. Hughes. In this book, Hughes argues that the 1960s and 1970s were a time in which both the genres of soul and country became places where black and white southerners teased out and re-shaped ideas of southern identity in the post-Civil Rights Movement era. Of course, other historians—Jefferson Cowie in Stayin’ Alive for instance—have also written about the 1970s as a period of cultural ferment in terms of white identity, especially in the American South. Not surprising, then, that the blues would be but one place where questions of  identity manifested themselves.

identity manifested themselves.

African American blues and rock singers in the 1970s argued whether white performers could correctly “sing” the blues. For Ray Charles, the blues was born “out of a special African-American group experience,” as paraphrased by Hollie I. West, who interviewed Charles.[2] This belief that the blues was special to African Americans precisely because of this relationship to African American history was something for which B.B. King also argued. And if you were black and not listening to the blues—well, various articles also expressed a fear among older African Americans that their legacy and heritage were being forgotten. Take notice of the language from this 1979 essay about white Americans singing the blues: “And while young Whites listen to traditional bluesmen, young Blacks support groups such as Earth, Wind and Fire and the O’Jays, musicians whose flashy style and breezy art fits the contemporary Black lifestyle—and dance steps—of young Blacks more than Muddy Waters’ or Joe Turner’s.”[3] In other words, the question becomes: what does it mean for African American culture when the blues is no longer in vogue?

King himself addressed the question several times during his career. It seemed that Ebony, not surprisingly, did a reflective piece on either him or the blues field itself. By 1990 King was quoted as taking notice of the largely white audiences he was performing for, and later on he argued that the blues was central to the African American experience. King stated: “More than anything else, it is important to study history, to know history,” he says. “To be a black person and sing the blues, you are Black twice. I’ve heard it said, ‘If we don’t know whence we came, we don’t know how to where we are trying to go.’”[4] Where  you stand on the blues becomes a statement for how you believe African American society must adapt to the future. It seemed for Charles and King both that the blues was an integral part of African American identity. Without the blues as a glue to hold African American identity together, to serve as a reminder of both good days and bad, the idea of being African American turns to dust—or at least becomes something unrecognizable to members of an earlier generation.

you stand on the blues becomes a statement for how you believe African American society must adapt to the future. It seemed for Charles and King both that the blues was an integral part of African American identity. Without the blues as a glue to hold African American identity together, to serve as a reminder of both good days and bad, the idea of being African American turns to dust—or at least becomes something unrecognizable to members of an earlier generation.

For intellectual historians, the questions raised by Ray Charles, B.B. King, and other musicians—not to mention intellectuals from this era—about the African American experiences become crucial to thinking about other questions plaguing thinkers at the same time. Consider questions about the urban crisis during the 1970s and 1980s. And then tie them back to what Charles and King express, which is a reluctance to celebrate white Americans embracing a “black” art form. While much of that is born out of their own experiences with segregation and the exploitation of black talent and labor in the music industry during much of the 20th century, it’s also an exploration of the questions black intellectuals posed in the 1970s and 1980s about the gains and, yes, inferred losses for African American society due to desegregation. Often black intellectuals, activists, politicians, and community leaders would look back to previous generations and argue, “Those families, those groups were more stable .What happened to us since then?” A nostalgia for a more united black past—one born out of the fires of segregation and, before that, slavery, but lost with the advent of desegregation—permeates much of the language surrounding arguments about the fate of the blues. That’s not to dismiss those concerns. But as intellectual historians we should never forget the importance of music such as the blues to demarcating generational lines of agreement, disagreement, debate, and discussion. Or, at the very least, we should consider them as echoes of larger cultural and intellectual debates—perhaps, even, the echoes wars or fractures of culture.

[1] This isn’t the place to get into discussions of Iggy Azalea—I am confident cultural historians will have much substantive to say about her in the future. However, it is worth noting how Eminem and Azalea have been contrasted with one another, primarily due to Eminem often giving credit to many of the black musicians who have influenced his music, whereas Azalea, a native of Australia, has been faulted for not doing the same. As this The Guardian piece argues, Eminem has “unequivocally demonstrated his love for hip-hop as a culture and a genre.” See “Pop Appropriation: Why Hip-Hop Loves Eminem But Loathes Iggy Azalea,” http://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/feb/11/hip-hop-appropriation-eminem-iggy-azalea.

[2] Hollie I. West. “Can White People Sing the Blues?” Ebony, July 1979, p. 140. It’s also worth noting that Charles argued that “If the blues ever gets sung by a White person, it’ll be a Jew that does it. They’ve known what it is to be somebody else’s footstool.” p. 140-142.

[3] West, 142.

[4] Lynn Norment, “B.B. King Talks About Love, The Blues, and History,” Ebony, February 1992, p. 46.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Robert, this is such a nice piece.

I am drawn to think a bit here about B.B. King’s music in intellectual-historical terms; I hope you will forgive my hitchhiking here.

We might take as our text this magnificent clip from a King performance at Sing Sing prison in 1972:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LWLAAzOBoBI

Let’s try to reconstruct the rhetorical situation here. Every public speaker knows the difficulty of making friends with an audience, how easy it is for a gesture of solidarity to come across as pandering, for a gesture of humility to come across as insincerity, for a joke to land badly or an aside to instill confusion. And let’s assume that to be a blues guitar player on a radical folk music bill in Sing Sing prison in 1972––let’s assume that the preferred music of those assembled is Motown and Stax and hard rock and R&B and salsa and country and western––and is a particularly difficult situation in which to begin speaking. (Think of how hard it would have been for anyone to follow Jimmie Walker!).

Then look at the ease with which King begins his patter, his relaxed palaver, his go-with-the-flow joking about the slow set-up and the slow feedback wail. Watch as he takes his music out of history and demography and sketches out a circle in which something sacred, a ceremony, will take place. And like all effective ceremonies, you are never exactly sure when it commenced; at some point you find yourself in it.

The easiest thing to do at this moment––what most musicians would do––would be to strike up the band. There is power in the wall of sound that an ensemble can summon; safety, too. But King does not do this. It’s hard to tell––maybe he is doing a little bit of call and response with his pianist, maybe just with the crowd. He is open, vulnerable. The silence, space, the opening of an envelope in which performer and audience coexist––all of this is a gamble. A wag could yell out an insult; the audience might start talking amongst itself, the spell could be broken before it takes effect. The wager is premised on love.

Gilles Deleuze offered as an example of the “event” Edith Piaf’s incorporation of the cracking voice into a new aesthetic synthesis. We might think of B.B. King in this light. (Piaf was not the only singer to lose pitch in a ghostly whisper, and King was hardly alone in inventing the electric blues guitar, but the collective character of these endeavors strengthens, rather than weakens, their eventicity).

King’s instrument, the electric guitar, was not invented to accommodate “B.B. King music,” any more than it was invented to accommodate “Jimi Hendrix music” or “Eddie Van Halen music”––it was developed, in the first instance, to make louder the Hawaiian steel guitarist’s woozy glissandi to bring to the foreground the four-on-the-floor strumming of guitarists playing Count-Basie-style big band music.

As if to remind us of the contingency of this technological situation, in this clip King’s guitar amplifier keeps picking up a buzz and a hum (probably the electrical sockets are not properly grounded). King incorporates the noise. The crackling and snow becomes part of the sonic tapestry.

An electric guitar is a sensitive surface, much more sensitive than acoustic instruments. King’s acoustic forbears––the Delta blues guitarists of the early 20th century––had to develop complex contrapuntal styles to fill the room with sound; we imagine the exceptions to this rule––Blind Willie Johnson’s stark dhrupads, Robert Johnson’s existential wails––to constitute intensely private forms of art, captured, miraculously, for whatever reasons, on recording equipment. When they played on the street, they had partners, they played “Yes Sir That’s My Baby” and accompanied tapdancers and patent medicine pitchmen.

Which is to say that from an elaborate cultural matrix, King made extremely strategic selections. There was not an intact “heritage” sitting there, waiting to be received and maintained (this is the fantasy of the white blues aficionado, Ralph Macchio in the film “Crossroads” or the grimacing men with ponytails and Ray-Ban sunglasses and $4,000 Gibson guitars who appear on the covers of the musical instrument wholesalers’ catalogs that come in the mail).

King’s signature was his vibrato, the oscillating tail he would place on notes. For thousands of years, musicians played instruments strung with animal guts or silk, developing gorgeous languages of intentional vibration, barely audible to all but the most proximate listeners. This pre-electric aesthetic situation was defined by the physics of acoustic finitude–once struck, and shaken, the note dies out quickly.

The event that B.B. King creates with the new instrument of the electric guitar is this: the shaken note can be heard above a band, by a crowd, and need never die out unless King chooses to stop it. This is a development as novel as Edison’s lightbulb, as aesthetically significant as Wagner’s Tristan chord (let’s be serious, much more significant than that).

With this capacity in hand, King is able to create the methexical meta-instrument for which he became famous––the circuit of voice (really, the face), the finger (usually the index finger, with the first knuckle lodged against the neck of the guitar, summoning vibrato by shaking the whole hand), the audience, and the band.

The “changing same”: King’s songs are often in the same keys; they often follow the same chord progressions; vocal melodies migrate from one tune to the next. The blues is “old”––King jokes with the audience, you think this is old folks’ music. But none of this is really true. It is true for the musicologists who want to make lists and find authentically German structures beneath every melody, it is true for the marketing departments of those entities that Chuck D class corPlantations, it is true for the credit card companies that will re-discover B.B. King and make his guitar “Lucille” a star of its appeal to the young and upwardly mobile in the year 2015––but for us, for the rest of us, it is not true, and we know it, but we forget it.

The point is that this shake of a note is different from that because it is happening now and you are here to hear it. It is a little wider or a little narrower, the attack is a little sharper or a little duller, the note chimes against a resonant chord or clashes as the accompaniment modulates. This utterance (now a man, now a woman, now a boss, now a worker, now a mortal, now a god) is different now, and different again now––here we see King as a theorist of what James and Whitehead called the “speciousness of the present”––because it is between you and me, and because now is different than then, and because your response––not my intention––will decide what it means.

Thanks for this post, because it really gets at why the *music* itself matters. Just reflecting on your response right now, the quality of music does matter to thinking about the intersection of cultural and intellectual history with American music.

I think I want to come back to this–I need to view the clip to properly respond, and I also want time to digest what you’ve said here, because it’s a lot!