In a piece for The American Conservative

, titled “In Defense of Difficulty” (and appearing the March-April paper issue), Steve Wasserman argues that something of an Arcadia of middlebrow thought existed from roughly the 1940s until around 2000. But the “New Information Age,” brought into being by the world wide web, deflated the positive intellectual climate of that period. As with the aftermath of the Dot.com bubble, the world wide web has brought only a kind of longer-term intellectual recession rather than the promised “radiant future.” Here’s how Wasserman characterized the dream:

The digital revolution was predicted to empower those authors whose writings had been marginalized, shut out of mainstream publishing, to overthrow the old monastic self-selecting order of cultural gatekeepers (meaning professional critics). Thus would critical faculties be sharpened and democratized. Digital platforms would crack open the cloistered and solipsistic world of academe, bypass the old presses and performing-arts spaces, and unleash a new era of cultural commerce. With smart machines there would be smarter people.

Instead, the internet has become “a vast Democracy Wall on which any crackpot can post his or her manifesto. Bloggers bloviate and insults abound. Discourse coarsens.”

I disagree, but, for now, my larger and more substantial response is to Wasserman’s characterization of a golden age of middlebrow thought that preceded it. That is not only an Arcadian, overly nostalgic vision of middle and late-century U.S. intellectual life, but also a distorted view of the effects of great books promoters during the same time period. Wasserman’s version of American intellectual history underestimates both pre-WWII complexities (whether vital or morbid) and those that have arisen since 2000. His mistake, like Russell Jacoby’s, has been to mistake upheaval and change as only, or primarily, degradation and decline. And, in relation to Wasserman’s argument about the last 15 years, his thinking will appear, in long form, in a forthcoming book titled The State of the American Mind: Sixteen Critics on the New Anti-Intellectualism. Not having accessing to the longer piece or the book, here I will only offer some preliminary points of concern in relation to the American Conservative piece. In the process I do not mean to devalue Wasserman’s and his colleague’s call for complexity, rigor, difficulty, and nuance in relation to today’s larger intellectual landscape. Those are admirable and needed traits. Rather, I have problems with the historical thinking about anti-intellectualism supporting those goals.

I. Pre-1940s Intellectualism and Anti-Intellectualism

Every age in U.S. history has its characteristic anti-intellectualism(s) and prominent strains in the history of thought, whether in relation to that age’s so-called intellectuals or the larger populace. In addition, it is often difficult to disentangle what is political and ideological (e.g. proposals and reactions) from what is a true antipathy to complexity, nuance, and difficulty. In other words, charges of anti-intellectualism are sometimes cover for political differences and social problems. Although we could go as far back as the founding and antebellum eras for examples of accusations of anti-intellectualism, and Wasserman references Hofstadter’s work on those periods, here I will limit myself to the Progressive Era.

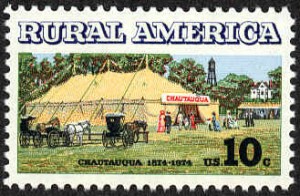

Although Wasserman argues that the post-WWII period witnessed the rise of a “cultural ecology that permit[ed] the second-rate to fail upwards,” the history of thought before World War II, and before World War I even, reveals a rich tapestry of thinking venues for adults, outside of small intellectual spheres, that might be attracted to non-elite thought. For instance, Chautauquas (i.e Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circles), began in upstate New York in the mid-1870s and spread around the country until the 1920s, functioned as “a company of pledged readers.” Those circles offered readings for participants, aspiring, as documented by Lawrence Cremin, for a “school at home, a school after school, [and] a ‘college’ for one’s house.” The goal was to “secure to [participants] the college student’s general outlook upon the world and life, and to develop the habit of close, connected, persistent thinking.” [1]

Chautauquas were more than just great books reading clubs for bourgeois or Philistine Americans. Members included teenagers, tradespeople, housewives, ministers, servants, teachers, and the elderly. They read “standard popular works” from contemporary authors such as John Richard Green, Charles Merivale, Henry White Warren, J. Dorman Steele, Richard T. Ely, Jane Addams, etc. Membership reached 200,000 during the 1890s and 300,000 by 1918 before a decline in the 1920s. Those numbers congregated in about 10,000 local circles, with “a quarter in villages of less than 500…and half in communities between 500 and 3,500.” [2] Chautauquas were conveniently ignored or underplayed in Hofstadter’s works (i.e. Anti-Intellectualism and Age of Reform, respectively). And it should be noted that this was only one of many non-elite forms of adult education in the late-eighteenth-century matrix of voluntary associations that included YMCAs, churches, libraries, women’s clubs, farmers’ groups, and settlement houses.

Chautauquas were more than just great books reading clubs for bourgeois or Philistine Americans. Members included teenagers, tradespeople, housewives, ministers, servants, teachers, and the elderly. They read “standard popular works” from contemporary authors such as John Richard Green, Charles Merivale, Henry White Warren, J. Dorman Steele, Richard T. Ely, Jane Addams, etc. Membership reached 200,000 during the 1890s and 300,000 by 1918 before a decline in the 1920s. Those numbers congregated in about 10,000 local circles, with “a quarter in villages of less than 500…and half in communities between 500 and 3,500.” [2] Chautauquas were conveniently ignored or underplayed in Hofstadter’s works (i.e. Anti-Intellectualism and Age of Reform, respectively). And it should be noted that this was only one of many non-elite forms of adult education in the late-eighteenth-century matrix of voluntary associations that included YMCAs, churches, libraries, women’s clubs, farmers’ groups, and settlement houses.

The kind of anti-intellectualism that arose in that environment and during the Progressive Era coincided with the rise of specialization, experts, and the universities. Standard textbooks on that era note the tension between social control/order and social uplift (or social justice) that existed among elite Progressives. Given the penchant for control, it is not surprising that some portion of the populace, educated and otherwise, might actively resist the top-down initiatives of experts and intellectuals. As Hofstadter himself noted, there was a “continued coexistence of reformism and reaction” in the period. He argued that “the Progressive movement was the complaint of the unorganized against the consequences of organization.” He added that “the central theme in Progressivism was this revolt against the industrial discipline.” [3] But it was during the Progressive Era, Hofstadter added, that “the estrangement between intellectuals and power…came rather abruptly to an end.” To purify and humanize politics and power, he wrote, “the functions of government would become more complex,” which, in turn, created a “great demand” for experts. [4] Those experts and intellectuals would necessarily have to be in control (exhibit “mastery,” in Walter Lippmann’s words) and organize the revolt against industrialization.

Thus the old “anti-intellectualism” was really about resistance to control (however necessary). Hostility to experts and intellectuals, in this context, could be about necessary restrictions to individual freedoms for the sake of the common good. Of course those experts overextended at certain points, repressing unnecessarily the cultural and religious pluralism of the nation’s new immigrants. Anti-intellectualism in those cases became a defense of identity and a reaction to unnecessary conformity. And what was the use of that authority or conformity in sparsely populated rural areas, such as in Plains states and out West? What expertise was required in those areas? And when Progressive intellectuals and experts supported President Wilson’s entry into World War I, the eventual backlash against the war necessarily included a new skepticism of intellectuals.[5]

When anti-intellectualism appeared, then, in this era, it wasn’t about resistance to nuance, rigor, difficulty, complexity, or cultural uplift. It was about skepticism in the face of a new form of power and new political framework.

II. The Great Books Arcadia, Revised

Early in his article Wasserman asserts the following:

In the postwar era, a vast project of cultural uplift sought to bring the best that had been thought and said to the wider public. Robert M. Hutchins of the University of Chicago and Mortimer J. Adler were among its more prominent avatars. This effort, which tried to deepen literacy under the sign of the “middlebrow,” and thus to strengthen the idea that an informed citizenry was indispensable for a healthy democracy, was, for a time, hugely successful. The general level of cultural sophistication rose as a growing middle class shed its provincialism in exchange for a certain worldliness that was one legacy of American triumphalism and ambition after World War II. College enrollment boomed, and the percentage of Americans attending the performing arts rose dramatically. Regional stage and opera companies blossomed, new concert halls were built, and interest in the arts was widespread. TV hosts Steve Allen, Johnny Carson, and Dick Cavett frequently featured serious writers as guests. Paperback publishers made classic works of history, literature, and criticism available to ordinary readers whose appetite for such works seemed insatiable.

And Wasserman mimics Adler’s and Hutchins’ democratic ideals, as great books promoters, when he wrote the following:

The pleasures of critical thinking ought not to be seen as belonging to the province of an elite. They are the birthright of every citizen. For such pleasures are at the very heart of literacy, without which democracy itself is dulled.

With all of this in mind, Wasserman adds that one might see “the middlebrow culture of yesteryear was a high-water mark.”

But Adler’s and Hutchins’ project, however noble, was more of a dream than a reality, both from the beginning and as time progressed in the postwar period.[6] Their aspirations did produce some successes. Sales of Britannica’s Great Books set started slow but eventually reached more than respectable numbers. A cottage industry of great books reading programs and adjunct sets followed. Colleges and universities adopted great books programs. Public awareness of the great books idea, Hutchins, and Adler were high. But numbers of great books reading groups—the dialogical heart of the great books program—never really rose as dramatically as did the sales. And despite some successes with some college programs, great books reading groups were primarily an adult education phenomenon built and maintained, by and large, by volunteer labor. In an age of abundance, the competition for adults’ evening and weekend time and energy was fierce (e.g. television, film, vacations, and other leisure pursuits). The sharpening of critical thinking skills were exchanged for relaxation and diversion. Paperbacks contained pulp fiction as much as great books and classics.

But Adler’s and Hutchins’ project, however noble, was more of a dream than a reality, both from the beginning and as time progressed in the postwar period.[6] Their aspirations did produce some successes. Sales of Britannica’s Great Books set started slow but eventually reached more than respectable numbers. A cottage industry of great books reading programs and adjunct sets followed. Colleges and universities adopted great books programs. Public awareness of the great books idea, Hutchins, and Adler were high. But numbers of great books reading groups—the dialogical heart of the great books program—never really rose as dramatically as did the sales. And despite some successes with some college programs, great books reading groups were primarily an adult education phenomenon built and maintained, by and large, by volunteer labor. In an age of abundance, the competition for adults’ evening and weekend time and energy was fierce (e.g. television, film, vacations, and other leisure pursuits). The sharpening of critical thinking skills were exchanged for relaxation and diversion. Paperbacks contained pulp fiction as much as great books and classics.

From the 1920s and into the 1950s, the great books idea–no matter its Western focus—was cosmopolitan in relation to the larger American populace. In this way the great books fought American-style parochialism and myopia. Great books forced U.S. readers to reckon with important European and Mediterranean strains of thought. Even if the great books idea was presented in a middlebrow fashion (to follow Joan Shelley Rubin’s line of thought), reading those works forced adults to think beyond the newspapers, radio entertainment, and beyond simplistic political ideology. In this way the great books idea fought America’s mid-century anti-intellectualism.

If the so-called “great books movement” had any success, it came primarily during the 1940s and 1950s. By the end of the 1960s sales of Britanica’s set had diminished, and the Culture Wars had already begun to fragment any sense of common identity (however real or false) that had helped maintain some consensus about great books lists. That fragmentation grew in the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in the late 1980s and early 1990s. If there was ever a great books-based middlebrow culture “that permit[ed] the second-rate to fail upwards,” it was gone by the late 1960s.

Did the great books movement fight anti-intellectualism? Surely. Was it the Arcadia Wasserman asserts? Maybe for a time. Most certainly not, however, for the full period he asserts. Did that great books movement allow for a higher critical culture, one that supported and appreciated the nuances of book criticism and intellectual integrity? Perhaps—again, for a time.

The power of the great books idea persisted longer in the academy than elsewhere. That’s why the great books idea, as it existed in college curricula, became a target in the 1980s. The old lists that supported those academic great books programs had not been adjusted to the new needs of rigor, neither for students, faculty, nor the citizenry at large. The historical thinking that informed the old lists was outdated. Not only had the domestic society and culture changed which the liberal arts had served, but a new corporate cosmopolitanism outside the academy demanded new cultural capital for understanding a wider range of consumers and employees. Given that, dissenting from the great books idea as it existed in the academy in the 1980s was not anti-intellectualism. Rather, the postmodern resistors were more sensitive to the changed human skills and sensitivities needed outside the academy–the world which higher education served. It was the defenders of the old great books idea that were, ironically, anti-intellectual in relation to the new, post-1960s globalism. It’s not that the books on those old lists weren’t great. Rather, different great books were needed to understand the new intellectual environment—i.e the new difficulties—of the transnational citizen.

III. The So-Called “New Anti-Intellectualism”

Wasserman asserts that a “new anti-intellectualism” has arisen since around 2000. How? For starters, he despairs that the old means of intellectual dissemination have been decimated: “Today, America’s traditional organs of popular criticism—newspapers, magazines, journals of opinion—have been all but overwhelmed by the digital onslaught: their circulations plummeting, their confidence eroded, their survival in doubt.” Without the old organs of circulation, Wasserman fears for the mental health of the populace.

The new means of dissemination privilege anti-intellectual modes. To make his point, Wasserman enlists the thinking of Leon Weseltier:…

[Next week will be the second and final installment of this reflection. – TL]

————————————————-

Notes

[1] Lawrence A. Cremin, American Education: The Metropolitan Experience, 1876-1980 (NY: Harper & Row, 1988), 432, 434-35.

[2] Cremin, 435-36. Cremin’s numbers come from John S. Noffsinger’s Correspondence Schools, Lyceums, Chautauquas (NY: Macmillan, 1926).

[3] Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (NY: Vintage, 1955), 21, 216

[4] Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (NY: Vintage, 1963), 197

[5] Ibid., 213.

[6] Much of what follows in the next 5-6 paragraphs is distilled from the work and thought I put into my book, The Dream of a Democratic Culture: Mortimer J. Adler and the Great Books Idea (NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Tim, this is a substantial and wonderful condensation of much thought. Really appreciate it you taking the time to think through it for us.

Sometimes when I see anti-intellectualism in a piece, I think what it really means is anti-intellectual. So called intellectuals, as commonly defined, often feel like they deserve more attention and space than they get. Of course like Wasserman, it’s all in the name of the people and their uplift. We are in a period of transition in the forms of communication and we still don’t fully understand the implication. However, thinking that there is magic in print is like those who railed against the printing press destroying oratory. Something new emerged, not necessarily better, just different.

Thanks Lilian. Next week, in part 2, I’ll discuss Wasserman’s ideas about this current period (2000-present). I’ll be anxious to see how the USIH community agrees or disagrees with his assessment. – TL

Tim, as you might imagine, I have Many Thoughts about your intriguing argument — but must save most of those for other pages. But a few stray remarks…

I am interested in your “splitting” of Progressive-era anti-intellectualism and your characterization of the rural manifestations of it as not being about a rejection of nuance but a rejection of control. Your use of the Chautauqua movement is interesting, especially read alongside/against James’s ruminations in “What Makes a Life Significant?”. With James, one might argue that what the Chautauqua’s represented was not necessarily intellectual sophistication or bracing thought; it was “bourgeois.” But whatever the term “bourgeois” might embrace, and however it might be tossed about as an insult (then or now), it was (and remains) an aspirational status for many. So in some sense the actual intellectual content of Chautauquas (and whatever else they might stand for in middlebrow culture) may have been less important than their packaging as an “intellectual” pursuit. I think this fits in with your own work on the Great Books set and the relationship between the book set as a material possession for display and the book set as a “curriculum” of sorts.

On the curricular changes of the 1980s…I am finding vestiges of what you would call the “great books idea” within academic discourse about revisions of the syllabus, but I find that idea more prevalent among non-academics. This may be a distinction without a difference — I’m still sorting this out. But my sense is that there’s a (probably) significant difference between the terms of the on-site arguments about reading lists and the for-public-consumption pronouncements about it in interviews w/ NYT reporters, book-length jeremiads about cultural decline, or what have you.

The chapter I’m writing now is on the “reception history” of the Stanford debates up to (roughly) the mid-1990s, and so part of the story I’m working out is how the debates were repackaged/repurposed for various polemical ends that often didn’t have a whole lot to do with the original dispute. Whinging about the Great Books in peril thanks to those tenured radicals at Stanford was a dependable way to gin up a mob in the 90s — still is, judging by fairly recent pronouncements of the NSA. But the polemic — it’s those damn French theorists! it’s cultural relativism! it’s a loss of all aesthetic standards! — bore a very tenuous relationship to the on-the-ground problem of what to put on the syllabus. Your gesture toward a certain kind of “anti-intellectualism” among the faculty resistant to “canon revision” is a partial match for some of the arguments put forward on behalf of Plato, Dante, and the gang — say, in resistance to the cultural turn — but your framing (at least so far) puts the “canon defenders” in the position of “obstacles to progress,” and I think that introduces a Whiggish undertone that you probably don’t intend. But I don’t know that for sure, so I am very interested to read your next installment! (In the meantime, I will keep on footnoting you and Andrew. You guys are “the literature.”)

That Chautauquas were packaged—and therefore consumed—as intellectual pursuits (not just careerism) is precisely my point. Just as I only partially doubted the sincerity of those who purchased the Britannica sets, I would only partially doubt the sincerity of Chautauqua consumers. In many ways I doubt the latter less, since Chautauquas were events that couldn’t easily be put in one’s den or living room. And, like great books reading groups in the 1940s and 1950s (and later), the consumption was largely of the intellectual activity of discussion.

I most certainly didn’t mean to make canon defenders sound, of a piece, like obstacles to progress. Great books lists, whatever the politics of their compilers, often contained a great deal of overlap. The changes were often on the margins, especially volatile in books published after 1900 or so. So my so-called “obstacles to progress” had lists that were probably (spit-balling) 75% alike the newer lists. They were often anti-intellectual (to my tastes) in their resistance to 25 % difference–to the additions and the larger ideas that drove progressives to add the newer books. That said, the revisers and progressives did not always present deeper, more sophisticated, and highly convincing arguments on behalf of newer authors. Neither side seemed willing to meet in the middle regarding list selection criteria.

I realize I’m speaking in generalities in this comment. I have some specifics in the book, but it would take some serious, list-by-list comparison over about 20 years to really suss out the particulars. – TL

Tim:

1) My forthcoming book on the legal and political legacies of rural school districts tracks closely with your argument about the preservation of “control” and local democracy. Indeed, I extend that argument up to the 1980s, arguing that liberal attempts at “mastery” and regulation pitted them against traditional notions of community governance, leaving conservatives free to invoke (and redefine) those traditions to their own benefit. Even today, accusing someone of anti-intellectualism seems to be a way to avoid harder questions about power, expertise, and public deliberation. So, yes, right on!

2) Your post also reminds me of one of my least favorite grad school books, Susan Jacoby’s “Age of American Unreason,” which seems to indulge in the same sort of nostalgia and glorification of the middle-brow that you raise here.

Campbell: That Jacoby book has weaknesses, for sure. And yes, I too think that it tended, at times, to glorify a false past. Otherwise, I’m pleased that my general sense (corroborated here only by my Chautauqua example) about the history of anti-intellectualism corresponds with our findings. I find that it’s *always* better to attribute more rather than less complexity to historical actors. – TL

I loved the intellectual culture of the 1950s and 1960s. My parents were like a lot of the folk in my neighborhood–real low-low-working class types who’d made good somehow (actually, thank FDR). My mother graduated high school, which was still rare in her day; my father never finished eighth grade (which wasn’t so rare–it was 1933, and everyone had to work, including the kids).

By 1960, they were well into the solid middle class, and the way you showed that was to aspire to gentility. That meant learning, and learning eant books. We subscribed to every TIME-LIFE series of publications there was (I suppose), and many others (Book-of-the-Month, etc.) one of which was a great books shelf that was at least five feet, not sure. Tim Lacy would have beamed.

My parents didn’t read them, but their kids did. Before I was 12 I had introduced myself to so many books, the one’s having the biggest effect including William Shirer, Karl Marx, Ulysses Grant, Pearl Buck, Herman Melville, and, most treasured of all, Thoreau’s Walden.

It really helped that there was really nothing on television worth watching in the afternoons. And that there was no way to get access to any of the interesting publications coming along (Rolling Stone magazine–which was really good then–started in ’67, but try getting a copy in a school library or any store within reach–they didn’t subscribe or carry it, for obvious reasons).

I still remember a kid who somehow got a copy of Ho Chi Minh’s poems. It got furtively passed from kid to kid when we were like 13, carefully hidden from parents and teachers, who would have thrown a complete fit if they’d found it. It was more dangerous than Playboy. It was dreadful poetry, but we were reading some poems–and sometimes longing for better.

It was a great time to be alive.

This era has a lot to recommend it–you never have to be at a loss for the name of that 1930s actor, or the exact date when Bob Dylan recorded “Like a Rolling Stone,” or even instant videos of, well, everything.

But there was a lot that was good about the comparative information-desert of those days. Sometimes you got stuck with an old book you’d never have actually chosen to read because there was literally nothing else to do.

Thanks for this, John. By the end of your comment you were headed to one of my points for next week. That is, we’re not more “anti-intellectual” now, but we’re very likely more distracted. Distraction has zero, however, to do with baseline capabilities today. And our intellectualism today has nothing to do with our format of reading, but it might have something to do with inequality, capitalism, and leisure time. – TL

Boy, are we ever more distracted. I recently got on Twitter. I suspect it will kill me.

I have little patience for the idea that the internet has made us anti-intellectual or that the variety of spaces it offers for intellectual communities is any more damaging than say, the partisan periodicals of the 1790s. There’s a lot of reasons for that skepticism, so I really appreciate this detailed post and the posts to come!

Likewise I am also more sympathetic, however, to the idea you’re talking about next time, that we’ve become constantly distracted and easy to distract. To that effect I can’t help always thinking of David Foster Wallace and Infinite Jest; some of his thoughts on this I think is captured in this video (apologies in a public space now w/out headphones so can’t double check) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39UJuPogwiY&list=FLHdDwGREO7-ke9mL1l48Esw&index=32

Ditto your first para, Robin. Next week’s post won’t be a definitive refutation of that notion, but I intend on starting the convo. – TL