The Vietnamese, Richard John Neuhaus declared in 1969, were “God’s instruments for bring[ing] the American empire to its knees.” Then a Lutheran minister speaking at a thee-day anti-war meeting assembled by Clery and Laity Concerned About the Vietnam War (CALCAV) in Washington, DC, Neuhaus later became a key architect of a movement to rebuild American moral authority in the shadow of Vietnam. In April 1971, following the trial and conviction of Lt. William Calley, the only American soldier convicted of a crime in the My Lai massacre, Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr told New York Times reporter Robert McFadden, “I think there is a good deal of evidence that we thought all along we were a redeemer nation. There was a lot of illusion in our national history. Now its about to be shattered….This is a moment of truth when we realize that we are not a virtuous nation.”

The Vietnamese, Richard John Neuhaus declared in 1969, were “God’s instruments for bring[ing] the American empire to its knees.” Then a Lutheran minister speaking at a thee-day anti-war meeting assembled by Clery and Laity Concerned About the Vietnam War (CALCAV) in Washington, DC, Neuhaus later became a key architect of a movement to rebuild American moral authority in the shadow of Vietnam. In April 1971, following the trial and conviction of Lt. William Calley, the only American soldier convicted of a crime in the My Lai massacre, Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr told New York Times reporter Robert McFadden, “I think there is a good deal of evidence that we thought all along we were a redeemer nation. There was a lot of illusion in our national history. Now its about to be shattered….This is a moment of truth when we realize that we are not a virtuous nation.”

The Vietnam War provoked a profound spiritual, or in the terms of Neuhaus and Niebuhr, theological crisis for the United States. The legacy of the war gave rise to a matrix of intellectual, cultural, and moral struggles. Movies that addressed everything from soldiering to surviving to constructing the war have played upon the broad “lessons” of the conflict considered through the intellectual histories of the Culture Wars and the Vietnam Syndrome. American popular interest in war as a force that defines the nation’s history and existential purpose often serves as fodder for historians who uncover the bitter aspects of the death and destruction of war, and the desire to forget both.

Next Thursday at 7pm at the Lilly Auditorium in the IUPUI Library, I will participate in a screening and discussion of Rory Kennedy’s The Last Days in Vietnam. Let the remem bering and debating begin again. With a Rotten Tomatoes rating of 95% and near unanimity of praise from film critics, Kennedy’s documentary about America’s dramatic exit from Vietnam comes with accolades that demand attention. Writing in the LA Times, Kenneth Turan said: “Sometimes the stories we think we know, the stories where we don’t want to hear another word, turn out to be the most involving of all, the ones we in fact know the least about. So it is with ‘Last Days in Vietnam.'” Like-minded David Denby writes in the New Yorker

bering and debating begin again. With a Rotten Tomatoes rating of 95% and near unanimity of praise from film critics, Kennedy’s documentary about America’s dramatic exit from Vietnam comes with accolades that demand attention. Writing in the LA Times, Kenneth Turan said: “Sometimes the stories we think we know, the stories where we don’t want to hear another word, turn out to be the most involving of all, the ones we in fact know the least about. So it is with ‘Last Days in Vietnam.'” Like-minded David Denby writes in the New Yorker

: “As a portrait of America in a moment both of idealism and betrayal, the movie is heartbreaking as well as inspiring.” Ann Hornaday in the Washington Post gushes: “‘The Last Days in Vietnam,’ at its core, is about moral courage – the bravery to confront the question of ‘who goes and who gets left behind,’ as retired Army colonel Stuart Herrington puts it.'” And David Edelstein adds to the praise chorus: “In sum, Last Days is the best kind of doc – it ties you up in knots.”

To investigative journalist and author of Kill Anything that Moves Nick Turse, those “knots” are laughable and nearly criminal (see Chris Hedge’s laudatory review of the book here). Turse contributed a scathing review of Kennedy’s movie to The Nation. He ends his essay taking direct aim at the moral of the movie–something for which critics have offered easy praise. “What kind of people seed a foreign land with hundreds of thousands of tons of explosives and then allow succeeding generations to lose eyes and limbs and lives? Only a ‘violent and unforgiving’ people could do such a thing. Someone should make a movie about that.” Rory Kennedy, Turse makes clear, did not–though she is more than willing to allow her “talking heads” to condemn the North Vietnamese as “violent and unforgiving” without a hint of irony or contest.

To investigative journalist and author of Kill Anything that Moves Nick Turse, those “knots” are laughable and nearly criminal (see Chris Hedge’s laudatory review of the book here). Turse contributed a scathing review of Kennedy’s movie to The Nation. He ends his essay taking direct aim at the moral of the movie–something for which critics have offered easy praise. “What kind of people seed a foreign land with hundreds of thousands of tons of explosives and then allow succeeding generations to lose eyes and limbs and lives? Only a ‘violent and unforgiving’ people could do such a thing. Someone should make a movie about that.” Rory Kennedy, Turse makes clear, did not–though she is more than willing to allow her “talking heads” to condemn the North Vietnamese as “violent and unforgiving” without a hint of irony or contest.

At least two other critics have echoed Turse’s reaction. Gerald Peavy

, the critic, film scholar, and producer of For the Love of Movies, complains:

Every American soldier interviewed in the movie is a decent humanist who’d been in Saigon because of his deep concern for the Vietnamese people. Some there learned to speak Vietnamese, others had Vietnamese families. The only CIA person on camera is a whistleblower, another great guy who did his best for the Vietnamese. And most telling is the guest appearance of Henry Kissinger, 91, repeating, yet again, his sad story of how the American Congress refused President Ford’s plea for additional funds in Vietnam, leaving those in Saigon dangling.

Steve Macfarlane expands on the trouble with Kissinger noting:

The withdrawal’s inherent moral dilemmas are made explicit; their relation to the material in hindsight are frustratingly under-considered. In some ways, the documentary is troubled by its dual focus on the nuts and bolts of the evacuation, and the larger policy gridlock that made it such a fiasco….That Kennedy can toggle between interviews with disgraced CIA agent turned whistleblower Frank Snepp—who wrote Decent Interval, the definitive firsthand account of the agency’s abandonment of its subcontractors in Vietnam—and none other than Henry Kissinger himself without a whit of irony speaks to the documentary’s political sheepishness.

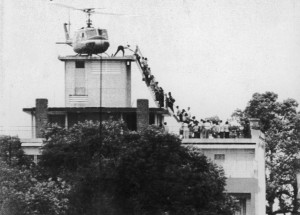

But Turse has the credentials and the material to go much further in his critique of Kennedy’s film, and, more significantly, the legacy of the war that he argues Americans have yet to grapple with fully. That legacy is bound up in statistics–close to four million violent war deaths, 2 million of them civilians and most of the in South Vietnam, Turse reminds his readers. That is part of the context (and content) missing from the film. Another problem is that by focusing on the “harried, haphazard, sometimes even mildly heroic efforts by Americans to slip South Vietnamese friends out of the country on planes, ships and finally helicopters as North Vietnamese forces push ever closer to the South’s capital, Saigon” Kennedy quite consciously “offers a classic American yarn about the good intentions of well-meaning American whose chief desire, in a land that their country had helped to decimate, is to save Vietnamese lives under difficult conditions.”

In the film one dichotomy between the American effort at the end of the war contrasted with the violence of the North’s final assault on the South, distracts attention from the more significant dichotomy, Turse argues, between the American violence unleashed for over seven years and the last pathetic efforts to save relatively few South Vietnamese. It also covers up the kinds of stories that fill Turse’s own book, such as the account of Ho Thi Van who joined the guerrilla resistance in the South after she witnessed American troops massacre her family. Turse finds Kennedy’s inability to address the ruthlessness of the American war effort a moral failure of the greatest historical order.

Should we or how do we share in Kennedy’s failure? Turse’s argument suggests that American audiences will have little historical memory or historical interpretation to bring to their viewing of the film. His essay begs the question of what he thinks he has done with his own work–has he opened our eyes to the atrocities of the war and depended deepened our collective sinfulness for the war?

Of course, few wars in American history have been scrutinized as much as Vietnam. If that scrutiny has not prevented similar mistakes from being made, well, there a few scholars who have written about that as well.

George Herring wrote a piece for Foreign Affairs just as George H.W. Bush attempted to declare an end to the “Vietnam Syndrome.” Herring pointed out bluntly: “For Vietnam the principal legacy of the war was continued human suffering.” For Americans who watched the Berlin Wall crumble and American troops rumble through a 60-day war in Iraq and Kuwait, Herring cautioned against seeing “Vietnam…as unimportant or irrelevant.” Indeed, Herring’s work along with Marilyn Young, Lloyd Gardner, and Fredrik Logevall, to name just a few, have at least provided a sound foundation on which Americans can approach Rory Kennedy’s contrived slice of the war.

But what about Kissinger–does his pass in the film reflect a larger sense of his role in history? In 2009, Jeremi Suri, a historian at the University of Texas, had his biography of Kissinger published. Suri has become something of lightening rod for debates about the history and capability of the United States to engage in nation building. And his biography of Kissinger did not start from the position of that the former Secretary of State was a war criminal, but that he Kissinger carried within his personal as well a s his professional history a narrative of the United States in the twentieth century. When discussing Kissinger’s orchestration of the American disengagement from Vietnam (something at the time that the press hailed as nearly magical) Suri explains: “By centralizing all decision making through his back channel [with his North Vietnamese counterpart Le Duc Tho], he lost touch with events on the ground. During his extended negations, more than 20,000 American soldiers died in action, and many more thousands of Vietnamese perished…The two men negotiated about the war, but they rarely grappled with the gruesome nature of the fighting. Kissinger, in particular, never seemed to question whether the national credibility he sought to preserve was worth the mounting human costs” (232).

s his professional history a narrative of the United States in the twentieth century. When discussing Kissinger’s orchestration of the American disengagement from Vietnam (something at the time that the press hailed as nearly magical) Suri explains: “By centralizing all decision making through his back channel [with his North Vietnamese counterpart Le Duc Tho], he lost touch with events on the ground. During his extended negations, more than 20,000 American soldiers died in action, and many more thousands of Vietnamese perished…The two men negotiated about the war, but they rarely grappled with the gruesome nature of the fighting. Kissinger, in particular, never seemed to question whether the national credibility he sought to preserve was worth the mounting human costs” (232).

Turse wants Americans to face the appalling atrocities committed and Rory Kennedy seeks to investigate how the United States left the war, though neither defines the totality of the war for either the Americans or the Vietnamese. Suri’s conclusion about the Kissinger’s role in the war rings true for Americans in general. While Kissinger “extracted the Untied States from a nightmare conflict in Vietnam…Kissinger never transcended the Vietnam War.” Americans have yet to do so and hopefully never will.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this timely post, especially the links to some wonderful folks and books, like Young (who has detailed the historically unprecedented scale of aerial bombing in Southeast Asia) and the volume by Turse (which documents much that should have been well-known long ago). It happens to be the 50th anniversary of the first teach-ins about the Vietnam War, which helped to mobilize and crystallize opposition to the war by students and others (including a significant number of U.S. soldiers) against our involvement in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Americans in general never seemed to have made a genuine attempt to understand or empathically feel just what the war meant and may still mean for the Vietnamese people who, despite the enormity of their collective suffering, have been remarkably forgiving. Indeed such forgiveness is conspicuous if only because of the lingering and devastating effects of the war on the people and their country (the latter involving long-term environmental effects): see, for example, the Wikipedia entry on Agent Orange, and this snippet on unexploded ordnance: “An estimated 800,000 tons failed to detonate, contaminating around 20 percent of its land. More than 100,000 people have killed or injured since 1975, the government says. But it doesn’t give out detailed information publicly and many casualties go unrecorded. Curious children picking up small cluster munitions make up a significant percentage of those killed or injured.” My wife was moved to tears when she listened to the Seymour Hersh interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy NOW!, and I reminded her that while many of our generation have heard of My Lai, they remain appallingly ignorant if not uninterested (and may be simply in states of denial) about much else that occurred during the war, in and outside of Vietnam proper. And if that is true of my generation, I shudder to think of how little this generation has learned about the war in “Indochina.” I trust you will not mind if I link to my bibliography on the war: https://www.academia.edu/5121042/Vietnam_War_select_bibliography_2014

Some weeks ago the PBS NewsHour ran a piece focused on a couple of American ex-soldiers who moved to Vietnam in recent years and have founded organizations, one of which is concerned w/ removal of unexploded ordinance. The lead-in to the NewsHr piece reminded me that this (or last month to be precise) is the 50th anniv of the intro of US ground forces in a combat role in S Vietnam. (I wd suggest that it is that anniversary, and not the 50th anniv of the teach-ins, that is the historically more significant anniversary. Not that the teach-ins were unimportant, of course.) That in turn prompted me to write a post on my blog “The 1965 Vietnam Decisions Fifty Years On.” (Link to follow in next box; there is a also a comment thread, fwiw.)

http://howlatpluto.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-1965-vietnam-decisions-fifty-years.html

Apologies for the awkward second sentence.

Thanks Patrick. I have great benefited from your different bibliographies. The screening will have a moderated discussion between a South Vietnamese national who is in the movie, a representative of a local veterans for peace organization, and most likely one other person to help the audience discuss the film and the history it shows and doesn’t show.

Thanks for these reflections, Ray, and for the bibliography, Patrick! Both are very helpful as I’m beginning to think through my diplomacy class this Fall. I plan to use Meredith Lair’s Armed with Abundance (paired with David Ekbladh’s Great American Mission and Victoria de Grazia’s Irresistible Empire) to get students into the war. Lair’s book finally helps me understand “Col. Kilgore.”

Add to bibliography:

John Newman “JFK and Vietnam” (an absolutely essential volume and real game changer in terms of how you will think about Kennedy and the war and the JCS and how LBJ changed things.) Probably the most important book about Vietnam

Michael Herr “Dispatches” beyond essential and the best book about the troops

John Hellmann “American Myth and the Legacy of Vietnam”

Norman Mailer “Why Are We in Vietnam’’ and “Armies of the Night”

Tim O’Brien’s ‘’Going after Cacciato” and “If I Die in a Combat Zone Box Me Up and Send Me Home”

Gloria Emerson “Winners and Losers”

John Laurence “The Cat from Hue”

Ron Kovic “Born on the Fourth of July”

Karl Marlantes “Matterhorn”

John Sack “M”

Alfred McCoy “The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia”

Peter Dale Scott “The Kennedy Assassination and the Vietnam War”

Thanks for the suggestions: I have to look over (preferably read) titles before I add them and please bear in mind this is not meant to be anything near exhaustive so I’m sure there’s lots of titles others would like to see added. I’ll look these over before the next updating of the compilation. And the Laurence book is in fact included.

Missed it sorry

Great post.

I wonder how much our “civic religion” impairs our nation’s ability to understand the ruthlessness and violence of the American way of war. Even today during the “global war of terror,” the media transmits messages from our leaders that our ordinance is dropped with incredible precision, and we, as a nation don’t target civilians.

The culture is even more militarized now as when I was young. Just check out the Opening Day festivities in baseball and note the veterans being honored, military flybys, etc. It is always three veterans on the ice during the national anthem before Chicago Blackhawks’ games never three teachers or firemen.

We as a profession, are also guilty. Take a close look at the textbooks used in your freshman U.S. survey course and examine the passages concerning our nation’s wars with the various indigenous tribes throughout our history and see how they are whitewashed. One could substitute “Indians,” for “Vietnamese” in this post and the essay would be valid.”

these words spoken by Hermann Goeriing at the Nuremberg trials, I think hold particular resonance for your comment:

“Naturally the common people don’t want war; neither in Russia, nor in England, nor in America, nor in Germany. That is understood. But after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine policy, and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is to tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country.”

I recommend reading Journalist Uwe Siemon-Netto’s book Triumph of the Absurd. His look at the Vietnam war and how it affected the people is a very poignant look at the lives touched by the war. 1517legacy.com is his site, great read.