It seems to me, for some reason, that lately over the pages of this blog and elsewhere we have rekindled discussions over the difference or ‘pastness’ of the past as compared with the present. Are historians too eager to find difference in the past that similarities go unnoticed, or is it the other way around? How familiar or different is the past? It would seem that as historians we have a vested interest in arguing for difference, since it renders our profession as that much more necessary—and alluring. And while it is quite impossible to argue that the past was not qualitatively different from the present, I think that too often—as present minded people—we regard particularly the modern period as standing on a different ontological plain altogether. I have always found the scholarship of Norbert Elias as one of the best correctives for this quite natural inclination to fetishize modernity. In what follows, I would like to convince you that his ideas offer us a viable alternative–one that regards the past both as very different from the present, yet on the same ontological plain we today inhabit.

I remember very clearly the first time I heard of Norbert Elias. I was sitting with some fellow history majors in the cafeteria of the Humanities building at my alma matter, the year was 2005, I was a third year, eager undergraduate, and I was reading Discipline and Punish by Foucault for the first time. I lifted my head from the book, made eye contact with another history major I knew fairly well and said something like “wow, this book is blowing my mind.” In response she gave me a half compassionate half condescending look and replied, “yeah, it’s alright—except that it’s wrong. Have you read Elias? Now he had it right, and he wrote it 40 years earlier.”

I was of course bewildered, who was this Elias and why haven’t I heard of him? Here I thought that I was getting ahead of the game, but alas, apparently I still wasn’t one of the cool kids. With time I figured out the reason my fellow student reacted the way she did—it was because she was interested in medieval history. And medievalists, at least in my university it turned out, begrudged Foucault both his sentimentalization of the premodern period and his leading role in promoting the paradigm of the great schism in history between the premodern and the modern. Thus, I learned that medievalists were often quite critical of Foucault’s work, accusing him of historical simplification and teleological, cherry-picking, empiricism. More importantly, however, I learned about Norbert Elias, who, as I found out, many medievalists had since the late 1970s viewed as the best alternative to Foucault. For them Elias offered not only a more gradual and accurate longue durée

rendering of the process of ‘individuation’ than Foucault’s, but also an analysis that reckoned with the premodern era with due historicist nuance.

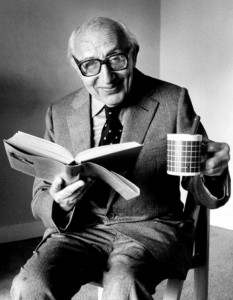

Though Elias wrote his seminal work The Civilizing Process in 1939, it was only towards the late 1970s that his scholarship became well known. By the 1990s—unfortunately only after he died—it was canonized as one of the great theoretical achievements of 20th century Sociology. However, even today, his work is not very familiar to many in the American academia, achieving much greater prominence in Europe.

The Civilizing Process is a masterful piece of historical and sociological analysis that views the slow change over time of social cohesion in Europe from the high medieval period to the modern period. It’s greatest insights stem from Elias’ ability to tether the transformation of everyday habits of people to a much larger macro vision of social change over a millennium. Elias’ central concern is with the notion of ‘civility,’ or ‘civilization.’ Examining the changing literature on manners in Europe, Elias argues that the general trend towards what Europeans regarded as a greater level of civilization revolved around greater constraint people exhibit in their most basic conduct. Thus he follows changing table manners, changing codes regarding the dealings with bodily excrements, the transformation of behavior in the bedroom, and much more. Such refinement of habits, which had originated with the medieval aristocracy, spread over the centuries to lower strata of society, as they sought to imitate the form of those who employed elaborate manners to assert superiority. According to Elias, by the modern period most Europeans had developed an elaborate system of constraint, imposed both by oneself and by one’s social surroundings, that governs one’s most basic acts. Though quite implicit and careful on such points, Elias insinuates that such changing configurations of habits constitute the contours of the transformation of the ‘self’ over many centuries.

The refinement of manners, argues Elias, also had important ramifications in organizing and controlling the violence in European societies, which had once been dominated by bands of armed nobles. This point also provides Elias with the crucial link between micro and macro levels of analysis, as he charts the consolidation of nation states. Following in the footsteps of Max Weber, he traces the centralizing forces that would culminate in the state’s claim to monopolize violence and levy taxes, thereby taming the aggression of the old manly ideal.

Though many, including myself here, have sought to tap the full potential of Elias’ ideas, he himself was quite hesitant to make unequivocal claims, which I think many medieval historians appreciate. Elias repeats time and again that the process he traces is far from linear, had no clear beginning and no clear end. It was rather a process rife with ebbs and flows and that exhibited certain patterns that he tries to identify. Furthermore, Elias attempts, with varying degrees of success, to purge the term ‘civilization’ of its moral implications in western imagination for the purposes of his project. This however, is to a certain degree in vain. Indeed, the heritage of the word civilization haunts the work, at times in a productive way, in other instances—especially as a title—it compromises Elias’ project to a certain extent. It is perhaps important to note that the word civilization and the title in German have a different linguistic connotations than in English, and that Elias begins his work with a drawn-out discussion of the terms ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’ in German, French, and English.

One of the best features of Elias’ work is that it is very accessible. Though his ideas are challenging and penetrating, he puts them in very straightforward terms. Unlike too many theorists, he does not seek to sound profound, but rather to deliver profound ideas in an intelligible fashion that is well grounded in concrete empirical findings. Particularly for historians, I believe, he provides an example of historical and theoretical work that explains change over time—a very long time—in a pithy and compelling package.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Lovely piece. I always think of Elias as complementary to Foucault, but perhaps there is more tension there than I had imagined. Would love, too, more discussion on the rich term ‘historical ontology.” Ian Hacking’s book of the same name comes to mind, and also Jameson’s A Singular Modernity. In any event, very nice stuff here.

Thanks Kurt. I think that for many who are interested in the modern period primarily they have seemed similar–for good reason–but premodern historians take issue with Foucault’s flawed empirical work, which makes sense as well. As for historical ontology , I must admit that I was kind of winging it, and don’t recall having heard it or thought about it before. But I’d also be interested in such a discussion. I would be happy to better understand what I meant by it.

Elias is a big name in European history, but he doesn’t seem to be assigned much. I don’t recall him being on any syllabus or reading list I ever had. Foucault on the other hand, showed up again and again. At any rate, it’s great to see him getting some attention, especially where one wouldn’t normally expect to see him getting it.

A few may be interested in exploring some of the uses of Elias in contemporary sociology, especially in the UK, such as in the work of Peter Burke and Stephen Mennell. Both have published articles in the last few years in the open-access journal Human Figurations, supported by the Elias foundation. Mennell drew on Elias most recently in The American Civilizing Process, 2007. There’s also a recent collection of critical articles by Francois Depelteau and Tatiana Savoia Landini, eds, Norbert Elias and Social Theory, 2013. Perhaps attention to Elias will grow as more people get interested in big, bigger and biggest, or deep, history, and perhaps the “deep future” too – as in Livingston’s ongoing inquiry on modernity, but also Kahlil Chaar-Pérez’s allusion to Chakrabarty’s work the anthropocene [USIH 3.7.15]