The following brief essay is part of my contribution to a roundtable at the American Society for Church History annual conference of which I am, quite happily, a part. I will complete the post next Friday with some comments on how the panel went and my proposal for a project on just-war and Catholic thought. The panel is below:

The following brief essay is part of my contribution to a roundtable at the American Society for Church History annual conference of which I am, quite happily, a part. I will complete the post next Friday with some comments on how the panel went and my proposal for a project on just-war and Catholic thought. The panel is below:

Studying American Religion, Politics, and Foreign Policy All at the Same Time: Where Do We Go from Here?

Sunday, January 4, 2015: 2:30 PM-4:30 PM

New York Hilton, Harlem Suite

Chair: Andrew Preston, Clare College, University of Cambridge

Speaker(s):

Raymond Haberski, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Darryl Hart, Hillsdale College

Christine Leigh Heyrman, University of Delaware

Leo P. Ribuffo, George Washington University

Like Andrew Preston

, my interest in religion and American foreign policy rose rapidly in the days after 9/11 as I watched and read the series of speeches and sermons that poured forth from preachers to the president.

But my awakening belied my ignorance of a tradition that I came to study in God and War. And my study of American civil religion showed me how unexplored that tradition had been.

What I found especially irritating was the invocation of Reinhold Niebuhr again and again to promote a kind of muscular Christianity in which moral men make tough decisions in a dark time. In practice, this approach also appeared to justify doing horribly violent things for an abstract moral ideal.

The project led me to consider a debate infused with religious language regarding the morality of making war and the tradition that seemed to emerge out of this debate of viewing war as an opportunity for national sacrifice and national redemption.

Writing about that tradition alerted me to the counter-traditions and alternative voices to the kind of godspeak that I think Preston has done a better job than anyone else of documenting and analyzing.

We now for the first time really have a view of what that dominant tradition is. Preston has mapped religion onto the entire history of American diplomatic history.

This achievement is substantial because his subfield of diplomatic history had persisted in thinking that religion mattered only when God or some other deity evidently changed the secular trajectory of American foreign policy—which wasn’t very often.

Preston assumed that religion mattered to policy makers just as religious historians have shown that race, class, gender, economics, etc. have mattered to preachers, theologians, and the faithful.

At base, Preston’s work changed the discussion about the relevancy of religion in US foreign policy. What surprised me about the reception of his work is that for many it seemed to end that discussion as well.

Ira Chernus, Bruce Kuklick, and David Hollinger all came to the same general conclusion that religion is either too diffused to isolate as a factor of influence (it is the air Americans breathe) or influential only under very particular circumstances.

At the moment, the historiographical conversation allows basically three levels of questions applied to the idea of religion’s relevance to American foreign policy.

- Political activity: Leo Ribuffo has argued religious groups and institutions matter just like ethnic groups or gender or political party affiliation when it comes to considering how religion influences foreign policy. The relationship between religion and foreign policy cuts both ways as well, with influence fluctuating according to the historical context and conditions.

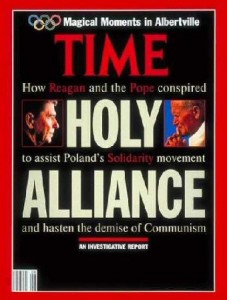

- Religious activity: When considering non-dominant religious groups, Wilson Miscamble contends that we should be circumspect about measuring the influence of religion on foreign policy and in the case of Catholics limit our understanding to those historical situations that are clearly demonstrable—for example, when Catholic evidently persuaded FDR to remain neutral in the Spanish Civil War. The conclusion is that Catholics neither wielded specific power over foreign policy nor influenced those who did in any appreciable way. While we might demonstrate that Catholicism offered an alternative to American foreign policy, but such evidence comes from minority groups within Catholicism or from trends within the church that did not last long.

- Intellectual activity: Preston’s argument is that religion in America has contributed an element essential to the culture in which foreign policy has been crafted, understood, debated, and sold. It matters that presidents, pastors, policymakers, and the people share common religious references, debate religious terms, use religion to critique and support foreign policy, and offer often conflicting religious interpretations of the world. The point he emphasizes can only be made and understood through a comprehensive narrative of American history—religion in American foreign policy operates on two levels, first as a language that affords successive generations of Americans to make common references; and second as a tool with interpretative power calibrated to specific conditions of a historical moment. Religion provided general or national context while also being used within specific religious traditions to forward specific foreign policies.

However, Preston did not seek to map American diplomatic history on to the history of religion in the United States. That approach would not make sense if, as David Hollinger pointed out, only a specific Protestant elite or, in the later Cold War, a Protestant infused ecumenical elite, had genuine influence in American foreign policy. But it might make sense if we look the history of Catholicism in America an alternative imperial narrative.

More next week.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great panel, Ray, and important opening remarks. Can’t wait to see how the conversation unfolds–especially in light of the SHAFR roundtable (June 2014) which featured Ribuffo, Cara Burnidge, Molly Worthen, Ed Blum, and Emily Conroy-Krutz. See Dan Hummel’s review of the panel here:http://usreligion.blogspot.com/2014/06/religion-and-u-s-foreign-relations.html

Wish I could have been there Ray. I look forward to reading your review of the panel.