Seeing Selma in theaters Friday night was a moving experience. In recent years, since beginning my training as a historian in earnest, I’ve approached films based on historical figures and events with a critical eye. Often this means watching a historical biopic with a mix of joy (a film I can care about!) and trepidation (my gosh, did they even listen to the historical consultant during this scene?). When it comes to films about the African American experience, in particular, my heartstrings are often ready to be tugged while my brain is on guard against historical inaccuracies. With Selma, the essence of the fight for voting rights is captured on film in a vivid and memorable manner.

Director Ava DuVernay’s film shows a Martin Luther King, Jr. (played by David Oyelowo) at the height of his international prestige and national political power. Starting with King receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, Selma moves back briefly in time to September, 1963, to portray the murder of four young girls at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. In her opening scenes, DuVernay captures both the international stage on which King operated as a national civil rights leaders, and the intensely personal cost some Americans paid for the price of basic human dignity.

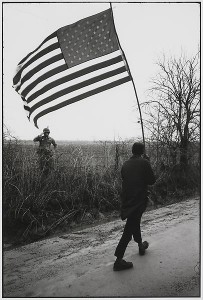

I knew the deaths of the four little girls was coming—but the scene jolted me just the same. Violence is a key part of Selma, and it has to be. The threat of violence lurks everywhere King and his cohort when they enter Alabama. And of course violence and the use of force is at the heart of the climax of the film—the brutal attack by Alabama troopers on peaceful protesters at the Edmund Pettis Bridge on March 7, 1965. Violence, of course, would claim the lives of Dr. King and so many others in the Civil Rights Movement. The acts of violence perpetrated upon activists would also play a role in sparking national conversations about the citizenship rights of African Americans.

The film has a sprawling cast of characters, a who’s who of activists known to all civil rights historians and many American historians. It’s unfortunate, however, that we barely get a sense of who these people were—Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young, Diane Nash and James Bevel, among others. Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce) and John Lewis (Stephan James) get a little extra dialogue and development on screen, largely due to their presence at the “Bloody Sunday” incident from March 7, 1965. It’s too bad Selma wasn’t made into a miniseries, instead of a feature film. More time could have been given to these activists, and still more devoted to activists native to Selma such as Amelia Robinson (Lorraine Toussaint), if it weren’t for the limits of a feature-length film.

Selma may have been better off being called King. It reminded me in many ways of the 2012 film Lincoln. Both films portray beloved American heroes in pivotal moments in their public and private lives. Not your standard biopic, Lincoln chose to focus on the sixteenth president’s determined drive to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, through Congress while also wrapping up the American Civil War. Both films were also criticized for historical inaccuracies—Lincoln for leaving out figures such as Frederick Douglass and Selma for downplaying President Lyndon Johnson’s support for the Voting Rights Act.

Selma and Lincoln both speak to present day concerns about national politics. With Lincoln, Tony Kushner carefully laid out Lincoln’s pragmatism against the aggressive idealism of Thaddaeus Stevens and other abolitionists–seen by some as a commentary on liberal disillusionment with Barack Obama. DuVernay, however, desires to show a film about civil rights centered around the activists themselves, and not the machinations of the White House. In a recent NPR interview, DuVernay stated that she had no intention of portraying LBJ as a villain, but simply wanted to make the activists in Selma the central protagonists. Perhaps this is fine for a feature film—although, as I noted above, the film’s really about King more than any particular group of activists. It reminds me of debates among historians about a top-down versus bottom-up approach to history. In other words, when we privilege the actions of the White House, or the activities of grassroots organizers on the ground, how are we portraying the history of that moment? Is it  distorted? Or is it simply one interpretation of an event? After all, while LBJ is not exactly the hero of the tale, he’s not the villain either (that role’s occupied by Governor George Wallace and Sheriff Jim Clark). And I’d go so far as to argue that DuVernay’s portrayal of the movement—while perhaps focused too much on King alone—shows a comfort with the grassroots and a distrust for the presidency that is a striking difference from Kushner and Lincoln. Perspectives matter, and the perspective of Selma is that of a movement battling for voting rights due to, as King himself would say, the “fierce urgency of now.” This, too, is a perspective that speaks to modern concerns about local movements and grassroots protesting–concerns from long before protesting began concerning Michael Brown or Eric Garner.

distorted? Or is it simply one interpretation of an event? After all, while LBJ is not exactly the hero of the tale, he’s not the villain either (that role’s occupied by Governor George Wallace and Sheriff Jim Clark). And I’d go so far as to argue that DuVernay’s portrayal of the movement—while perhaps focused too much on King alone—shows a comfort with the grassroots and a distrust for the presidency that is a striking difference from Kushner and Lincoln. Perspectives matter, and the perspective of Selma is that of a movement battling for voting rights due to, as King himself would say, the “fierce urgency of now.” This, too, is a perspective that speaks to modern concerns about local movements and grassroots protesting–concerns from long before protesting began concerning Michael Brown or Eric Garner.

DuVernay’s film is a clear example of a yearning for a Civil Rights Movement narrative that privileges the black experience. Selma is heavily focused on King. Down the road, perhaps, a different film about Selma will be made, in which MLK is a character often mention but hardly seen by hardworking activists. And I agree that any film based on a historic moment should be scrutinized for inaccuracies and lapses in factual correctness. But I do believe Selma

captures the moment of early 1965—the attempt to continue the fight for full equality in American society for African Americans. There are brief mentions of Vietnam, and glimpses here and there of King’s own evolution in thinking about civil rights, economic rights, and human rights. But above all, Selma gets to the heart of the campaign for voting rights in the winter and spring of 1965.

Go see Selma. There are parts of the film, whether concerning LBJ or the local activists, I wished had been done differently. I think it’s a shame Selma wasn’t part of a longer miniseries about the Civil Rights Movement. But Selma is worth seeing, and worth feeling as a film.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I saw it yesterday too, in Vancouver–escaping from MLA insanity!–, and I was wondering when Robert would post about it! The theater was almost packed, mostly by elderly white folks. I cried rivers of tears, the beauty of this movie is, aside from its aesthetic effectivity, and its echoes in the present, the nuanced, humanistic treatment of King, how the film goes beyond the “one man” narrative, showing how the movement was a complicated, tense social landscape of negotiators and resistants that came from different worlds and with experiences and outlooks. Beyond the obvious historical quibbles (which are very well captured here: https://www.thenation.com/blog/194473/what-selma-gets-right-and-wrong-about-civil-rights-history), I did ask myself a bit about the representation of SNIC. It was a bit reductive (some would say dismissive of James Forman). Regarding the length of the movie, seeing how many Hollywood produced movies come out now near the 3 hour limit, one could argue that Selma could have done more to include those other peripheral characters a bit more…but these are tiny quibbles, about what’s clearly a formidable film.

Thanks for the always informative comment! Glad to see my review met your expectations. And yes, when I walked out of the theater I was surprised to realize the length of the film was only about two hours. But the story still felt effectively told, quibbles and all.

Thaqnks for this review, Robert! I’m hoping to go see this film with my 60s class which is meeting right now.

Is there any sense of irony in the film–that it’s coming out at the same time that states are gutting the Voting Rights Act?

Thanks! And I don’t think there’s any irony in the film itself–although DuVernay herself has noted what’s going on in interviews.

You could make a case that a line from King while he’s in prison lamenting that there’s so far to go might be a reference to both his activism from 1966 to 1968, and also the current situation. But nothing more explicit than that.

Robert — great film and a great review! I saw Selma yesterday and had two thoughts. The first was that MLK needed to be the center of the movie because of the kind of reconciliation that takes place around his figure. Ultimately, Malcolm X, SNCC, LBJ, and even Coretta Scott King rally around the cause that needs to be represented, in film at least, by a single character. My second thought is that David Oyelowo’s portrayal of King emphasized his combative character over other features of this personality. Even the cadence of King’s voice in this movie had more urgency that the historical King.

Both excellent points. You’re right that the King in this film is a person everyone else looks to–whether they want to or not.

As for the delivery, I hadn’t thought about that, but that’s a novel, and quite good, analysis.